The Cold War, which went from about 1947 to 1991, wasn’t exactly a war, but a period of extreme tension and distrust between the Soviet Union (and its states) and the United States (and its allies). Political and economic issues abounded while wacky, fear-induced propaganda was in full force. And yes, this trickled right down into the kitchen.

According to Brittanica, it was writer George Orwell who coined the term “cold war,” in an article published in 1945, referencing a stalemate between “monstrous super-states” that possessed a nuclear weapon. Clearly, that name was spot-on and it stuck.

After World War II ended and Nazi Germany surrendered in May 1945, the Soviet powers set up governments in eastern Europe. This was a concern for the American and British governments, who feared Soviet takeover moving from the East to the West, where democracy was established.

Of course, the Soviets wanted to keep control and spread communism.

Directly opposed to this ideology, the Americans did everything they could to aid the western European countries — especially ones at risk of being crumpled in the Soviet takeover. Throughout this ideological war, several impactful events occurred, making their mark on history as we know it: the Berlin Wall, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Space Race, and so much more.

(If this weren’t a food blog, this piece would be very different!)

But the War didn’t just play on between governments.

Citizens were clearly affected by the Cold War. As Hyperallergic says, “Differences in worldview during the Cold War generally found expression in geopolitical doctrine, economic policy, or the words of politicians and pundits. But for the great majority of the population, these differences were reflected in the mundane objects and rituals of everyday life, the most universal of which is food.”

Food can symbolize a lot more than what is merely on the surface.

On the American end, the “red scare” definitely led to food rebranding, refusal to eat certain foods, and on the other hand, an ethnic fetishization around certain dishes.

So, what did people eat? For one, a nation that is constantly worried about being bombed to smithereens from faraway forces might have some food preparation strategies at hand. Namely, they might stock up on and buy canned food. It’s cheap — and, you know, it’s easy to hide in bunkers and bomb shelters. For this reason, the Americans chowed down on beans and hotdogs.

According to Mental Floss, a recipe from Curtis Publications, published in 1973, includes green beans, potatoes, and bacon.

Then there were the so-called “ethnic” recipes that began finding a place in American cookbooks. Cringe.

These coincided with the years when the Cold War began making its way into Asia. In one recipe, which includes corn starch, celery, and luncheon ham (hi, yuck?), you’ll find that America had no freaking idea what a Chinese meal might even remotely look like. Luncheon ham? That sounds pretty uninformed to us.

Other problems with Chinese foods existed, too.

Like the kiwi. Wait, back up — don’t kiwis come from New Zealand? Nope. There’s a Cold War link to kiwis, too! The Chinese Gooseberry (AKA kiwifruit, AKA kiwi) is thought to have originated in New Zealand, but it was actually a New Zealander who brought kiwifruit seeds back to his country from China in the early 1900s. Around the 1950s, New Zealand took a hit when trying to export kiwis to Americans, as the Americans didn’t want to touch a communist fruit called Chinese Gooseberry.

Changing the name to kiwifruit apparently worked (and stuck), because the American anti-communists ate it up. Literally.

It wasn’t just the kiwi that had a role in the Cold War.

So did everyone’s favorite sandwich, smoothie, and health bowl ingredient: the banana. In the 1950s, Chiquita Banana (then called United Fruit Co.) grew their bananas in Latin America — making money from a “banana republic” that relied on crops for earnings and taking advantage of its workers. Naturally, Guatemalan President Jacobo Arbenz Guzman wanted to buy some of the unused land owned by United Fruit Co., but they were not having it. And so, just like that, they accused Guzman of being a communist.

The Americans then invaded Guatemala, killing hundreds of thousands, and ensured the power stayed with the United Fruit Co.

As you can see, the “red scare” drove people and companies to act in ways that are unethical and horrific, perhaps even more than they were already. This allowed them to become foreign powers that retain control of another country’s agriculture. Turns out that throwing the word “communist” around could, unfortunately, be used to one’s advantage.

Oh, and take a look at this, delicious, er, ham and bananas recipe from 1947, a year into the Cold War:

Moving on from the fruits:

Ever order chicken Kiev at a restaurant? You can thank the Cold War for your delicious community dish. Basically, this chicken breast stuffed with butter and herbs (or lots of other things today, like cheese) comes from Russia. It was a popular dish in the early 1900s, according to The Calvert Journal, where Soviet hotels and restaurants served it up. When diplomats from America and England tried it, though, they were sold.

Even England’s Marks & Spencer began serving it as a ready-made dish, and it became a hit in 1979, according to The Book of Spice.

We’re not sure how kiwis took so much flack while chicken Kiev was given a pass!

When you think about burger joints like Burger King or Mickey Dee’s, do you think about communism? Now, you will! Throughout the ’60s and ’70s, when Americans began gobbling down fast food like it was going out of business — this hasn’t changed — they had no idea that the Cold War would have an impact on the chain restaurant.

As one Reddit user says, “The Big Mac is a symbol of American globalism, for many.”

Comment

byu/IslaVista7 from discussion

inAskHistorians

By the ’80s, though, tensions began diminishing, and so McDonald’s began moving out East, staking claim first in communist Belgrade, Yugoslavia.

Because so many other chain restaurants saw that a new market was receptive to fast food, the going got tough. Chains began competing with one another — driving down prices, offering toys (yes, the toys you LOVED as a kid were used as a way to drive people in eastern Europe to buy meals!), and play areas.

#Mindblown

But it wasn’t just food that played a role in the Cold War.

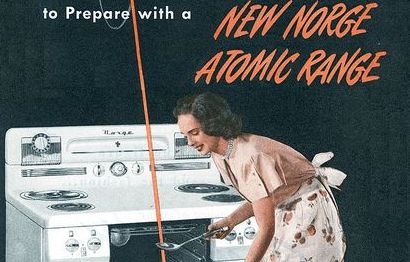

It was the idea of a kitchen — and food creation — itself that divided the East and West. In a 1988 Los Angeles Times piece titled, “Women Stayed at Home During The Cold War,” the author wrote about how the kitchen was a symbol of American capitalism and women’s domesticity (a “conformity to a powerful family ideology”) — as opposed to communism and women working.

The Cold War was an especially symbolic time.

As the L.A. Times author writes, how a family should operate became a “kitchen debate” between then-Vice President Richard M. Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita S. Khrushchev in 1959. Nixon felt that an ideal home life was one in which capitalism reigned supreme as a woman had the ability to use household appliances.

Capitalism and communism clearly had their differences, even when it came to a woman’s place in the household.

Just like food, our appliances also have a great meaning.

These labor-saving appliances symbolized America, in a way, in its attempt to showcase a glamorous, stay-at-home wife — someone different from a hard-working Soviet woman. This propaganda drove more and more American families to create a kitchen that functioned both as a place to make food (and keep women’s autonomy at a minimum, to put it nicely) and to disavow communist thinking.

Who knew appliances could mean so much?

Pretty wild, right?

On the Soviet end, especially during the Cold War, what was the cuisine like? It’s borscht and cabbage, sure, but that’s an oversimplification. According to an article in Taste, from a writer born in Russia, “The Soviet culinary canon incorporated dishes from all over the empire: the area that is now Russia, but also Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan.”

Again, there is a difference between Soviet and Russian food.

In fact, there is no precise “Soviet” food — it’s a mixup of many foods, and to reduce it to “Soviet” food, which often was interchangeably and incorrectly called “Russian” food, would be reductive. As the writer says, the cuisine was basically invented by the political sphere. “Everything was grown, canned, sold, and marketed by the government… By digesting the food, you digest[ed] the ideology along with it,” said Anya von Bremzen, who wrote Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking.

Most of it was egalitarian, according to Culture Trip: You’ll have found Russian Salad, canned foods, and food from stolovaya, or state-run cafeterias that deemed home-cooked food as bougie.

In the end, it’s clear that food is a product of the ways we think — about ourselves and the world around us, and what we have access to. So, the next time you’re in line waiting to order a dish that originated in another country, you’ll have a lot to think about: Why is it popular? Who brought it here? Why are we embracing these foods?

And most importantly, who is at the bottom of the food chain?

After all, food is a language that tells all.