The Wild True Story of the Actress Who Slept Beside Lions

Tippi Hedren was on track to become one of Hollywood’s biggest stars. After her breakout role in The Birds, the spotlight was hers. But behind the scenes, she developed an obsession with wild animals—especially lions—that slowly took over her life. They weren’t in cages. They lived with her. On the couch. In her bed. Near her daughter. This wasn’t a bored actress acting out or struggling with fame. It was a ticking time bomb with claws — and a real-life story far more extreme than anything her horror-film career ever dared to show.

The Living Room Had Claw Marks

The walls bore scratches deeper than any child could make. Claw marks carved into drywall, sunlight slanting across a pawprint on the carpet. This wasn’t a zoo—it was home.

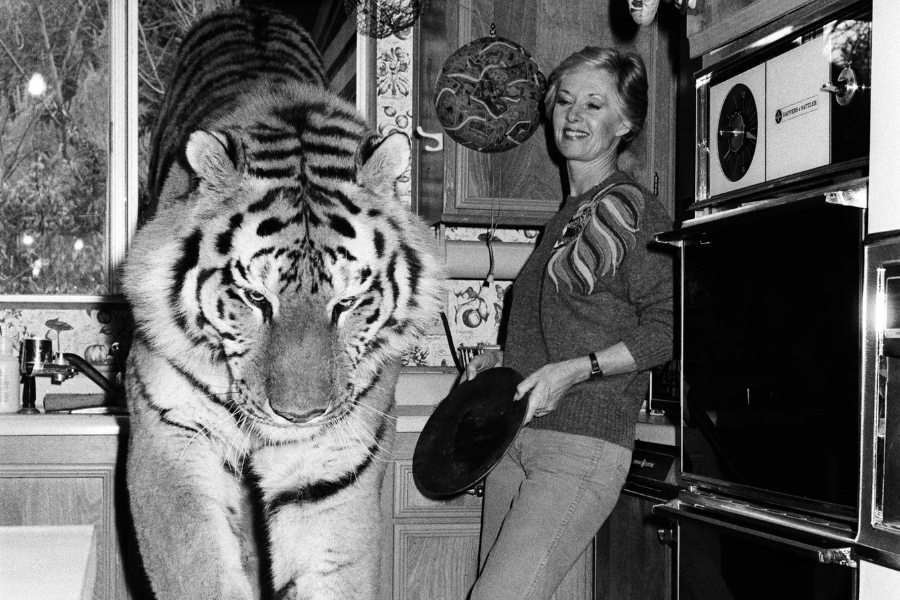

Tippi Hedren stood barefoot, sipping tea as a lion named Neil dozed nearby. Visitors gasped. To her, it was ordinary. Her kitchen was a savanna of stainless steel and whiskers.

The surreal normalcy unnerved even her closest friends. But Tippi wasn’t playing house—she was rewriting it. And the lions weren’t going anywhere.

A Model, A Muse, A Mystery

Before the beasts, there was the billboard. Hitchcock spotted her in a Sego commercial—poised, mysterious, controlled. He needed another icy blonde. He sent a cryptic invitation with no audition.

Tippi, a single mother and model, accepted the role in The Birds. One day, she was anonymous; the next, America watched her face shatter under beaks and wings.

But the man behind the camera was watching more than just the film. Hitchcock’s gaze lingered off-set. And his obsession with his muse was only beginning.

The Blonde in the Birdcage

She thought she was acting, but The Birds was more real than anyone warned her. The final week of filming featured live birds—pecking, clawing, and drawing real blood.

Tippi’s calm shattered under flapping wings. Between takes, she cried. She wore sunglasses to hide bruises. The director watched without intervening. He claimed it would make the scene “authentic.”

When she collapsed from exhaustion, he barely flinched. Something had shifted. Her trust in him—once absolute—was cracking beneath the cage.

Hitchcock’s Obsession Turns Cold

After The Birds, he cast her again in Marnie. But this wasn’t mentorship—it was control. Hitchcock dictated her wardrobe, her schedule, and her studio interactions. She felt like property.

When she refused his advances, the consequences arrived quietly. Roles dried up. Phone calls went unreturned. Hollywood, loyal to its kingmaker, turned cold to the golden-haired actress.

After Marnie, Hedren found herself quietly frozen out. She turned to smaller roles—TV movies, guest appearances, European films. She kept working, but the momentum was gone. She needed a wild redirection.

A Starlet in Exile

Tippi left the studio lots for something quieter. A trip to Africa offered her peace, perspective, and something unexpected. In the golden dusk, she locked eyes with a lion.

The connection was instantaneous. Not fear, but fascination. She saw power without cruelty, instinct without manipulation. It was everything Hitchcock wasn’t—and she wanted to bring it home.

That choice would alter her life, her daughter’s future, and leave behind a trail of blood, fur, and fire because some creatures, once welcomed in, never leave quietly.

The Trip to Africa

In 1969, Tippi Hedren and her family traveled to Mozambique for a film project. What they found wasn’t a script, but nature, untamed and electric, roaring just beyond the frame.

They stayed in a ranger’s compound near lions. One night, they watched a pride roam freely outside their bungalow. They needed no fences or barriers. Seeing them unrestricted under moonlight was a breathless awe.

Then, that moment burned itself into Tippi’s imagination. She didn’t just want to remember it—she wanted to live it. And she wanted to bring it back.

“Let’s Live With Lions”

Back in California, Tippi and her husband, Noel Marshall, hatched a wild idea: to make a film about humans living with lions. But they needed authenticity. Real lions.

They bought one, then another, and then more. Soon, their home in Sherman Oaks, California, transformed into a sanctuary, sort of. The bedrooms had pawprints, and the refrigerator held steaks for creatures with fangs.

Melanie Griffith, Tippi’s teenage daughter from a previous marriage to actor Peter Griffith, lived among them. She would one day become a star in her own right—but for now, she walked into adolescence with amber eyes watching her every move.

Introducing Neil, the 400-Pound Roommate

Neil was their first lion—400 pounds of muscle, mischief, and mood swings. He liked sleeping on beds, licking Tippi’s neck, and knocking over lamps with casual indifference.

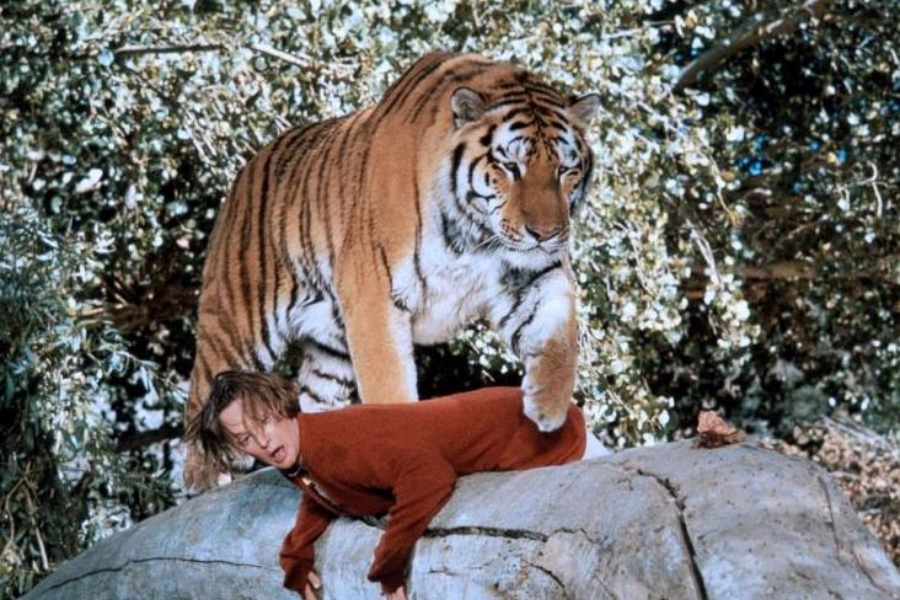

He was photogenic and eerily gentle—most days. Life magazine featured him lounging beside Melanie, his head bigger than her torso. Viewers were captivated. No one questioned the danger.

But lions are not pets. And even Neil, the “safe” one, had instincts sharper than any leash. All it took was one bad day.

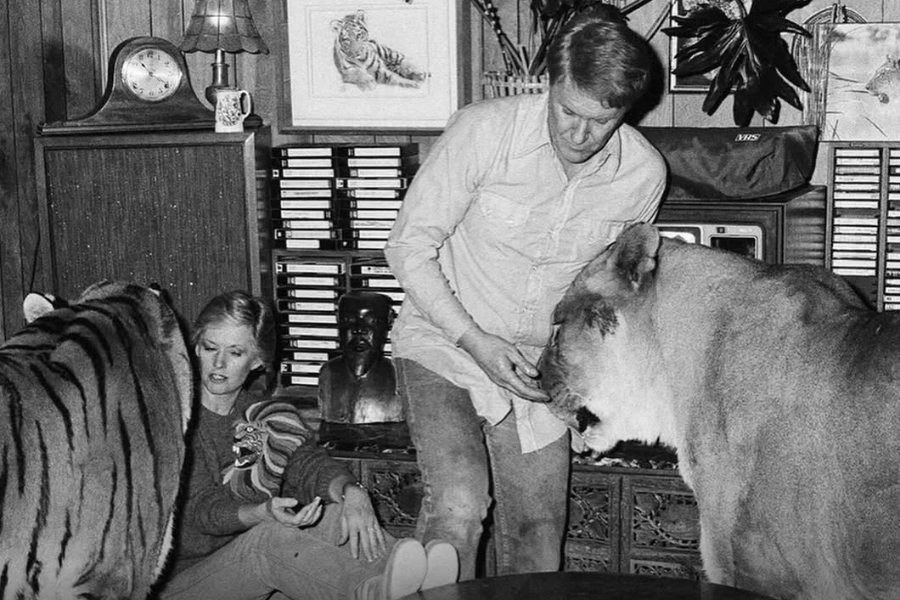

Wild Cats on the Kitchen Counter

Morning routines became surreal. Tippi flipped pancakes while a leopard leapt onto the kitchen counter. Melanie brushed her teeth beside a lion licking the porcelain sink.

Guests had to sign waivers. Broken furniture was replaced weekly. Despite the chaos, Tippi insisted they weren’t reckless—they were coexisting. Sharing space with nature, not controlling it.

Yet behind every playful pounce was power. They were guests in their own home, and the housecat rules didn’t apply when your roommate had fangs.

Melanie’s Homework Beside a Predator

Melanie did algebra while a lion lounged nearby, tail flicking, yellow eyes watching. She’d grown up with them, their growls as familiar as rainfall, their presence unremarkable—until it wasn’t.

One afternoon, a lion playfully nipped at her ankle. It drew blood. Her mother said, “He didn’t mean it.” But the bandage on Melanie’s foot said otherwise.

The line between coexistence and danger blurred daily. And it was a child—not a handler—who was first to realize how thin that line really was.

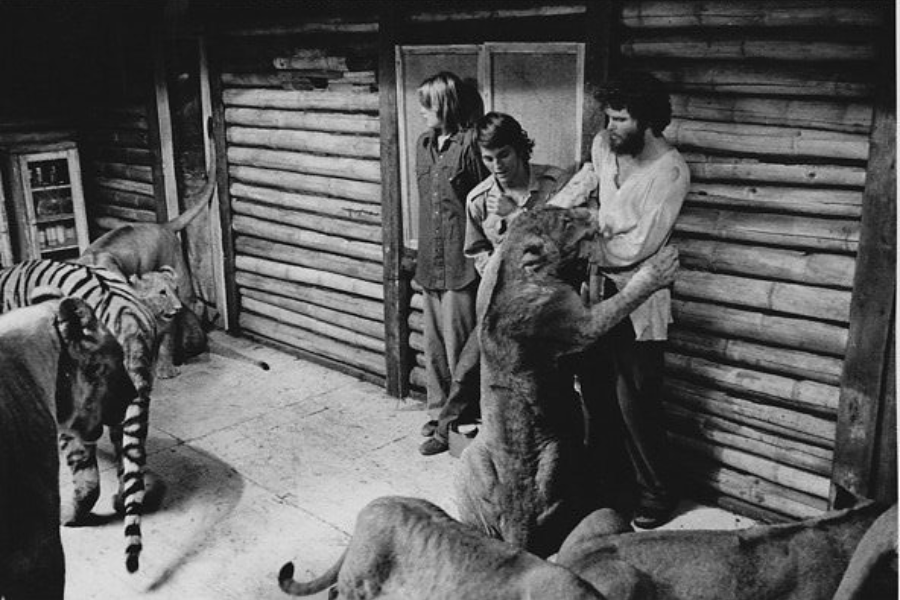

Lions in the Pool, Tigers on the Roof

The family pool became a watering hole. Lions splashed, played, and sometimes fought. Water turned amber from fur. The chlorine couldn’t cleanse what nature was reclaiming—one paw at a time.

A tiger once climbed onto the roof and wouldn’t come down for hours. Neighbors called it madness. Tippi called it “harmonious cohabitation.” The tiger eventually leapt, graceful, deadly.

Even sunlight seemed sharper at that house. Every shadow might twitch. And everyone knew, in their bones, that instincts don’t ask permission before they wake.

Neighbors Call the Authorities

The neighbors tolerated it for months. Then one lion escaped through a back gate. It wandered near a local school before being corralled back—no one was hurt, this time.

Phone calls flooded animal control. Authorities arrived, stunned. The house was legal—but barely. Tippi held permits, but not patience. She argued, “They’re safer here than in cages.”

Officials left with warnings. No fines, no shutdown. But the neighborhood’s nerves were shredded. And the lions weren’t the only ones growing restless.

No Insurance Company Would Touch Them

Once filming began, insurers balked. No company would cover a set with untrained predators. Tippi and Noel poured their own money into Roar, risking everything—house, savings, attention, reputation.

Crew members quit. One grip left after a lion stared too long. Others stayed until they got scratched, bitten, or hospitalized. There was no safety net, no backup plan. Hedren had to focus more on this project than on her minor TV appearances.

The cameras continued to roll anyway. Every frame captured risk in motion, and the financial, physical, and emotional cost was climbing faster than anyone could stop it.

Roar: The Dream That Turned Violent

Roar was supposed to be heartwarming—a family living with big cats, promoting conservation. But reality roared louder. The lions didn’t act. They reacted. And sometimes, they attacked.

Scripts were rewritten around injuries. A scene would begin with hope and end in blood. Tippi’s smile was real, but often forced between bandage changes and hospital runs.

The film’s tagline would later read: “No animals were harmed in the making. 70 cast and crew members were.” And filming wasn’t even halfway done.

A Set Drenched in Blood and Chaos

On day 128, a lion swiped at a crew member’s leg. He screamed. Arteries spilled onto the floor. Tippi knelt beside him, pressing towels as the cameras stopped.

Another week, a panicked assistant bolted and was chased into a van. Inside, he hid as a lion pawed at the locked door, growling, denting the metal panels.

Everyone was scared, but the film wouldn’t stop. They weren’t just making a movie anymore. They were trying to survive it.

Seventy Attacks—and Counting

In all, over seventy attacks occurred during Roar. Some were quick bites, others catastrophic. “It’s amazing no one died,” Melanie Griffith later told Vanity Fair. “We should’ve.”

Cinematographer Jan de Bont had his scalp torn open by a lion—over 120 stitches. Assistant director Doron Kauper was bitten in the throat. “I thought I was going to die,” de Bont recalled.

But Noel Marshall refused to stop. “We just need more footage,” he insisted. As blood dried on the floor, the camera kept rolling.

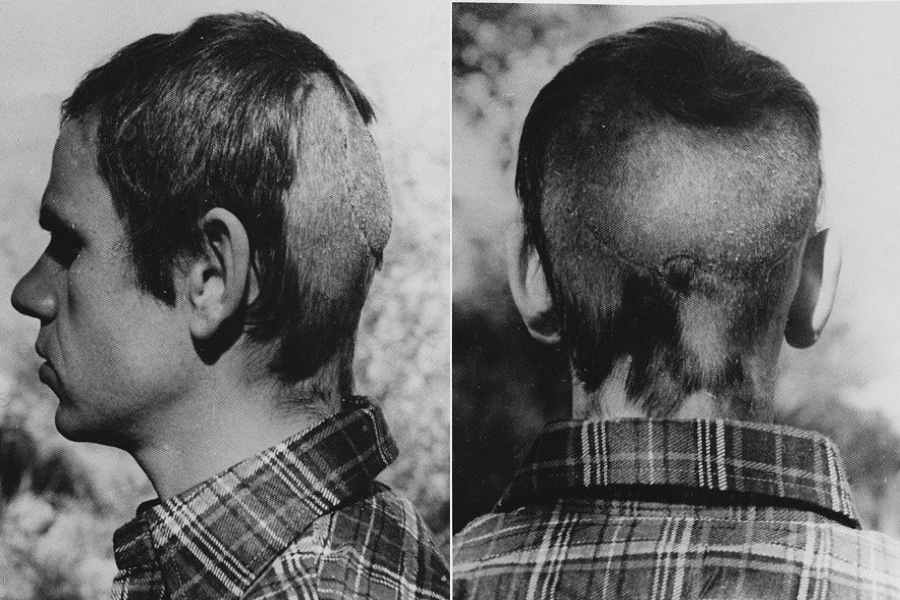

Jan de Bont’s Scalp Was Torn Off

Cinematographer Jan de Bont was filming low to the ground when a lion struck from above. “I remember feeling the warmth on my head,” he said. “Then everything went red.”

The lion had peeled back his scalp like paper. “Tippi held my hand while I waited for the ambulance,” he recalled. “No one screamed louder than her.”

He returned to work after healing. Imagine no lawsuits and no resentment? “That’s the crazy part,” he said. “We all came back—even knowing it might happen again tomorrow.”

Melanie’s Face Was Nearly Lost

Melanie was clawed across the face while filming a bedroom scene. The lion lunged with no warning. “He didn’t mean it,” Tippi said. But it was already too late.

Melanie needed reconstructive surgery. “It was so stupid what we were doing,” she later admitted. “No one had any idea how dangerous it really was.”

She returned to the set weeks later, stitched and shaken. Melanie grew up alongside her stepbrothers—Noel Marshall’s sons John, Jerry, and Joel. All were part of this chaos. And the lions weren’t finished with any of them.

More Bites To Come

Melanie wasn’t the only one scarred. Noel Marshall’s sons were the bait in the project, performing stunts, wrangling lions, and absorbing the risks their father refused to acknowledge.

John was bitten on the head—56 stitches. Jerry was mauled in the thigh and hospitalized. Joel, working behind the scenes, stayed safer, but no one was left untouched.

The lions didn’t care whose name was on the script. To them, everyone bled the same. And in that house, danger didn’t pick favorites. It just waited for its turn.

Production Stopped, Then Started Again

Production halted multiple times for injuries, legal threats, and weather damage. But Tippi and Noel never gave up. “We believed in the message,” she said. “We really did.”

Noel mortgaged their house, sold assets, and begged for funds. “It became an obsession,” Tippi recalled. “We were too far in. It was finish or fail.”

They pressed on. The house decayed. Crew morale crumbled. But the film had its claws in them now, and walking away felt even more dangerous than staying the course.

Filming Took Five Years and a Fortune

Roar took five years to shoot and cost over $17 million, most of it from Tippi and Noel’s own pockets. “We had no idea what we were doing,” she admitted.

Financial ruin loomed. “We had to choose between groceries and film stock,” she once told The Hollywood Reporter. Friends stopped calling. Studios wanted nothing to do with them.

And yet, the lions still needed feeding. The dream still needed finishing. And with every passing month, danger deepened—not just on screen, but in every corner of their lives.

The Final Cut: No Movie Was Worth This

After years of chaos, they completed Roar. The final footage was beautiful, raw, and completely unhinged. “It was like filming inside a nightmare,” one crew member later told reporters.

Tippi looked at the edit with disbelief. “I thought, we really survived that,” she said. But behind the survival was exhaustion—visible in every scar, every scene.

She once said, “No movie is worth someone’s life.” And yet, they had all come disturbingly close to making that exact payment.

Roar Bombs at the Box Office

Released in 1981, Roar was a disaster. It made less than $2 million. Audiences were confused. Studios had no idea how to market a movie built on blood and lions.

Critics were equally baffled. Roger Ebert called it “a fearsome folly,” while others questioned the sanity behind the project. “They should’ve called it Maul of America,” joked one review.

Tippi watched its failure quietly. She didn’t cry. “I was just relieved it was over,” she later said. But the aftermath wasn’t over yet.

Tippi’s Body, Bruised but Unbroken

Tippi’s body bore the memory: puncture scars, joint damage, nerve pain. “I had headaches for years,” she once told Esquire. “You try massaging lion trauma out of your neck.”

She began refusing interviews about Roar, redirecting focus to her advocacy. “That’s the real story,” she insisted. “Not the madness, but the meaning behind it.”

But people always wanted the madness. The blood. The lion in her bed. Her strength came from denying them easy answers—and living with what couldn’t be undone.

The Media Wasn’t Outraged—Yet

In the 1980s, few questioned the ethics. The public saw exotic animals as entertainment. “No one thought we were doing anything dangerous,” Tippi said. “They just thought we were weird.”

Tabloids called it eccentric. Headlines joked about “Hedren’s House of Hairballs.” Surprisingly, no documentaries, no exposés, no viral takedowns were made against them. The backlash simply… never came.

But times change. And when they did, Tippi’s lions would face a far harsher spotlight than anything ever captured on celluloid.

When the Lights Faded, the Lions Stayed

After filming wrapped, the animals didn’t leave. Over 100 big cats remained at the compound. Tippi and Noel were responsible for their safety, feeding, and futures.

The budget was gone. The staff had quit. The ranch became a cage without locks, where survival meant improvisation, sacrifice, and duct-taped fences. “It was overwhelming,” she admitted.

The cameras were gone, but the consequences had moved in permanently, even affecting Tippi and Noel’s once-perfect love.

The Cost of Obsession

The making of Roar didn’t just wound bodies—it fractured bonds. Once united by passion, Tippi Hedren and Noel Marshall’s marriage unraveled under the strain of their shared dream.

Years of financial strain, physical danger, and emotional turmoil took their toll. In 1982, Hedren filed for divorce, citing abuse, and secured a restraining order against Marshall.

What began as a shared vision ended in silence. The lions remained; the partnership did not. Roar had demanded everything—and left nothing untouched.

Founding The Roar Foundation

In 1983, Tippi Hedren created The Roar Foundation to legitimize care for the big cats left behind. It wasn’t just charity, it was a necessity. “They had nowhere else to go.”

Shambala Preserve was born from chaos. Fenced acreage, volunteer labor, and veterinary miracles became part of her daily life. “I became their voice,” she told the Los Angeles Times.

But even love comes with a cost. Feeding lions meant fundraising. Rescue meant regulation. And the line between sanctuary and penance blurred more with every rescued animal.

Shambala: A Sanctuary Built from Chaos

Located in Acton, California, Shambala became home to over 30 lions, tigers, and leopards. “Each one has a story,” Tippi said. “And most of them aren’t happy ones.”

She implemented strict no-contact rules for visitors. “We learned the hard way,” she told Hollywood Reporter. “These are wild animals, not playthings.” No more pool parties. No more bedrooms.

The preserve felt peaceful, but always pulsed with tension. One roar across the property reminded everyone that this was no zoo, and the past still prowled its edges.

Decades of Advocacy, Quiet and Fierce

Tippi spent the next decades lobbying for animal welfare. She campaigned against exotic pet ownership and fought for federal protections. “No one should own a lion,” she stated firmly.

She testified in Congress. She faced threats from breeders and circus operators. “I’m not afraid,” she said. “Not after what I’ve lived through.” The scars gave her credibility.

But part of her fight was internal. Because as she protected them now, she had to reconcile what she had exposed them to.

A Mother, A Matriarch, A Survivor

Behind the headlines, Tippi raised Melanie through disaster and fame. “She protected me the best she could,” Melanie later said. “But we were all in something much bigger.”

They clashed, reconciled, and evolved. Melanie respected her mother’s strength, but carried the weight of their lion years. “It wasn’t normal,” she once said. “But nothing in our lives ever was.”

Tippi, in turn, watched her daughter’s stardom bloom—and knew some legacies come with shadows. The hardest parts couldn’t be rewritten, only survived.

Melanie Griffith’s Wounds and Wisdom

Melanie has rarely spoken at length about Roar. “It’s behind me,” she once said. But when asked if it shaped her, she replied, “How could it not?”

She called it “a fever dream.” A story that, if told by someone else, she might not believe. “We lived with lions. That changes everything, even if you pretend it didn’t.”

At 17, she landed her first significant role in Night Moves (1975). Raised in chaos, she channeled that into Body Double, Working Girl, and a career built on survival. Even now, Melanie still talks about the lions to her daughter, Dakota Johnson.

Dakota Johnson Remembers the Lions

Dakota , the daughter of Melanie Griffith and actor Don Johnson, never lived with the lions, but their presence haunted the stories that shaped her childhood and, eventually, her career.

She became a celebrated actress in her own right, but never forgot her family’s strange legacy. “It wasn’t normal,” she’s said of her mother’s childhood with big cats.

She also recounted a disturbing incident involving Alfred Hitchcock, who allegedly sent her mother a doll of Tippi Hedren in a coffin, describing it as, “Alarming and dark and really, really sad for that little girl.”

The Final Curtain with Hitchcock

After Marnie, Tippi Hedren and Alfred Hitchcock never collaborated again. Their professional relationship ended amid personal turmoil and unspoken grievances.

Hitchcock’s obsessive behavior and Hedren’s resistance led to a permanent rift. She later revealed his threats to ruin her career, a promise he partially fulfilled.

Though she admired his cinematic genius, Hedren never reconciled with Hitchcock. Their story remains a cautionary tale of power, obsession, and the cost of defiance.

Tippi Reflects: “Would I Do It Again?”

When asked in later interviews if she regretted it, Tippi was conflicted. “I cringe when I see those pictures now,” she told The Mirror. “We were stupid beyond belief. We should never have taken those risks.”

She admitted to naiveté. “We didn’t understand what we were dealing with,” she said. “These animals are so fast, and if they decide to go after you, nothing but a bullet to the brain will stop them.”

Her voice softens when she says it. “But they needed to be treated with greater care than they were,” she once whispered. “Not as businesses.”

From Cage to Camera: The Legacy of Roar

In the years since, Roar has achieved cult status. Screenings draw stunned audiences. Documentaries dissect it. Filmmakers marvel that it even exists. It’s horror, comedy, and a cautionary tale combined.

Modern viewers watch with widened eyes. “They really lived with them?” one critic asked. “They really filmed through this?” Yes. Every wound in the film was real.

Tippi doesn’t flinch when people laugh or gasp. She just says, “That was my life. And we filmed the whole damn thing.”

Her Life in Pictures

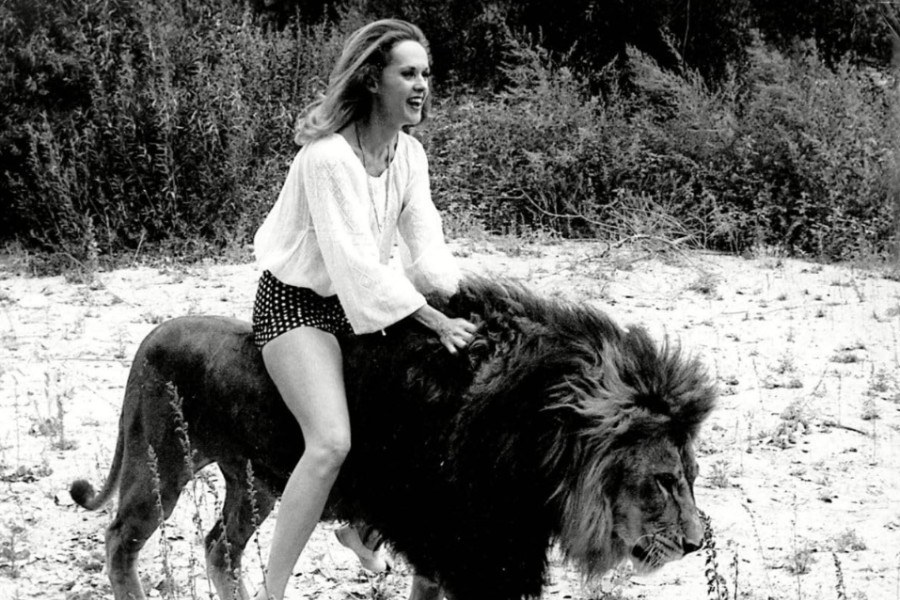

The photographs remain iconic. Tippi sunbathing beside a lion. Melanie smiling next to Neil. A jungle in the living room. They look surreal, even now, like dreams scribbled on Polaroid.

But look closer: the tension in her shoulders, the readiness in her stance. She’s poised not just for beauty, but for survival. Always waiting for instinct to wake.

These images aren’t fiction. They’re fragments of a life lived on edge, where glamour shared space with danger, and the wild slept on silk sheets.

The Final Look: Tippi and the Wild Things

At Shambala, years later, Tippi stands beneath the desert sun. “There’s a special connection you feel with a lion. It’s a bond of trust and mutual respect that is unlike anything else.”

She walks with grace and caution. A matriarch shaped by spectacle, trauma, and fierce conviction. She gave them her home, her warmth, her career. She never walked away.

The lions are distant now—protected, enclosed, respected. They no longer share her bed, but they still share her story, and they are meant to roar loud enough in the jungle, where they are much safer, for as long as they like.