They didn’t know it would be their last dinner. As the Titanic sailed into darkness, some dined beneath crystal chandeliers, others beside tinplate lamps and plain white crockery. For years, whispers of lost menus echoed through auction houses and estate vaults. What did the passengers eat before disaster struck? Now, more than a century later, the Titanic’s final dining records have resurfaced. And for the first time, we’re unveiling them in full. What was once reserved for private collectors and sealed archives is now yours to see.

The Last Full Day of Feasting

By dawn that Sunday, April 14, 1912, the scent of baking bread and simmering broth drifted through Titanic’s lower decks. Over 60 cooks moved with precision, feeding more than 2,200 passengers across every class.

The ship had left Southampton on April 10, bound for New York on a 7-day crossing. Now deep into the voyage, life aboard felt steady—eleven glistening courses in first class, hearty porridge and pudding in third.

Each day’s menu was freshly printed, slipped into crisp hands or tin trays. April 14’s editions would be the last—preserved like pressed flowers from a world about to vanish.

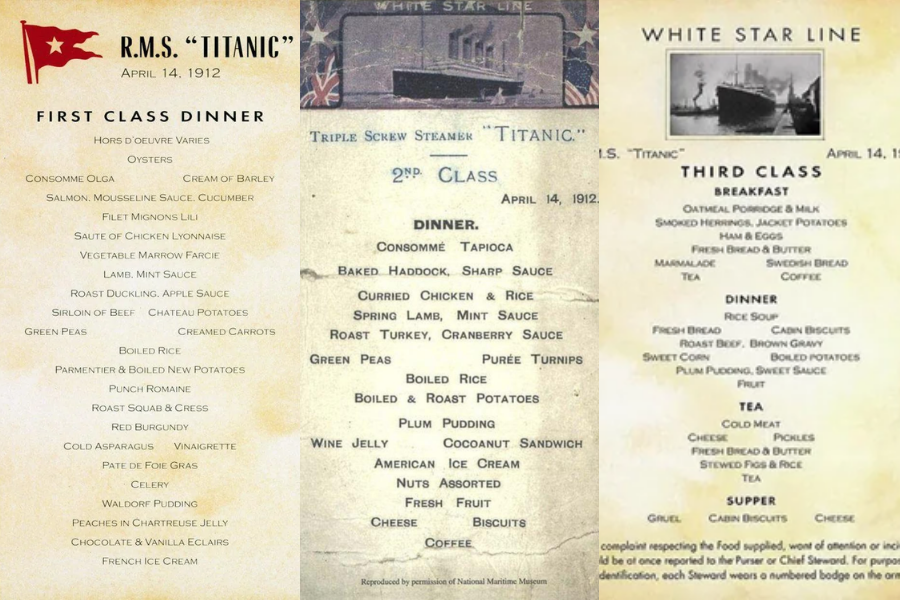

Three Classes, Three Realities

Titanic was divided by class, and nowhere was this more visible than in its food. Each menu reflected the expectations and economic realities of the passengers it served.

First class dined in Edwardian opulence, second class in respectable comfort, and third class with practicality in mind. All received carefully planned meals, regardless of luxury or simplicity.

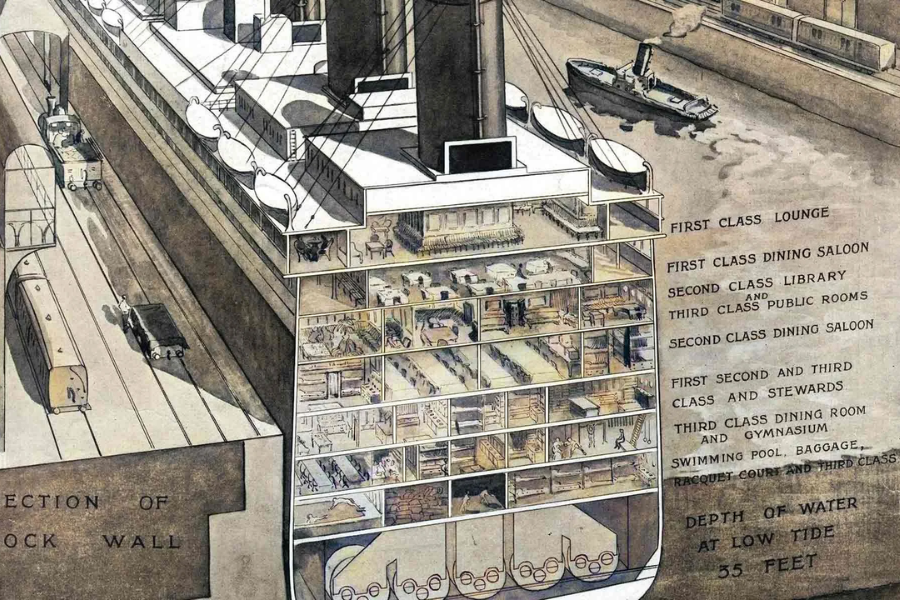

The ship’s electric elevator system served only first and second class. Third-class passengers climbed stairs instead—a literal reminder of how movement aboard the Titanic was shaped by social standing.

Third Class Breakfast

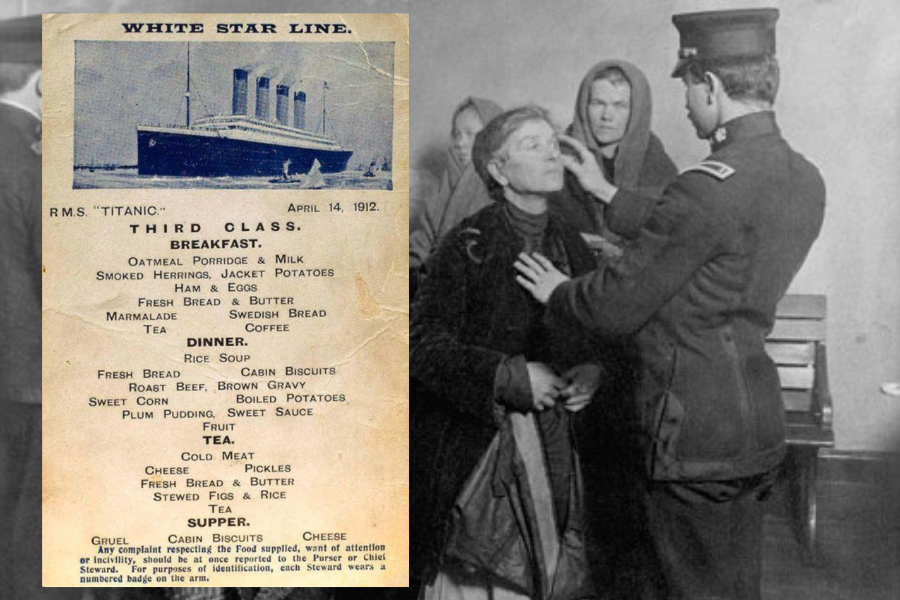

On the morning of April 14—the last full day aboard—third-class passengers sat down to oatmeal porridge, tea, and bread with butter. These were familiar staples for immigrants traveling from Ireland, Scandinavia, and Eastern Europe toward America.

Ham and eggs were sometimes available but not guaranteed. Third-class passengers were generally more accepting of whatever came on their plates.

The setting was plain: tinware plates, communal tables, and minimal service. But for many, this was the most substantial meal they’d had since leaving home or boarding a tender.

Smoked Herrings and Marmalade Dreams

Tea and dry biscuits were served with marmalade, offering a sweet treat. Fresh Swedish bread, a staple for Scandinavian passengers, was also noted in third-class food records.

Then came the smoked herrings and jacket potatoes. They were far more common—hearty, inexpensive, and suitable for a ship carrying hundreds in steerage.

Titanic researcher Bill Willard called third-class fare “far above average.” It was made to comfort and sustain. But even hearty meals had competition—dessert was about to steal the show.

The Third Class Midday Spread

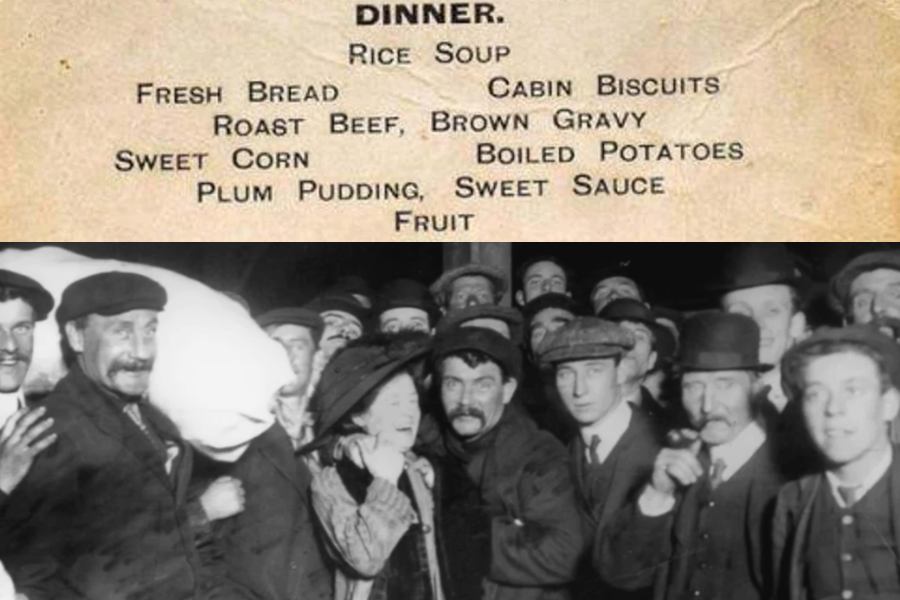

Lunch, referred to as dinner in third class, began with rice soup and bread. Though basic, it was served warm and paired with cabin biscuits or hard rolls.

The main course featured roast beef with brown gravy, boiled potatoes, and sweet corn. It was filling, familiar, and resembled a traditional British or Irish Sunday roast.

Dessert was plum pudding with sweet sauce. This menu—documented on recovered cards—shows that even in steerage, Titanic’s kitchen aimed to offer balance, taste, and a sense of dignity.

Rice Soup and Oatmeal

Rice soup served in third class was light, likely flavored with onion or bouillon. It offered warmth and comfort, especially for passengers unaccustomed to shipboard routines or ocean travel.

Gruel—essentially thin oatmeal or barley porridge—was nutrient-dense and cheap. Stewards offered it warm, sometimes sweetened. For cold Atlantic nights, it was a practical and sustaining option.

Photographs of Titanic’s galley confirm large soup vats and biscuit storage. These humble meals, shaped by budget and logistics, fed thousands with structure, not spectacle. And then, something sweet waited next.

Sweet Pudding and Sweeter Dreams

Plum pudding appeared on the third-class dinner menu, accompanied by a sweet sauce. It was dark, spiced, and dense—likely made in bulk and steamed in large molds below deck.

For many passengers, it was a rare treat. Dessert offered emotional lift and a momentary return to home kitchens, especially for British and Irish travelers heading to new lives.

According to culinary historian Dana McCauley, Titanic’s menus show that “steerage passengers were not overlooked.” Dessert, modest as it was, carried meaning. But by day’s end, the menu would grow quieter.

Cabin Biscuits

Supper in third class was light. Biscuits and cheese formed the core of the evening meal. It was designed to be easy on digestion and service logistics.

Cabin biscuits were dense and dry but practical. They stored well and doubled as utensils. Eaten with soup or jam, they were a dietary staple on long crossings.

Food historian Andrew Dalby notes that shipboard biscuits were “far from glamorous, but essential.” Just above them, though, porcelain plates and printed menus told a far different story.

Second Class Elegance

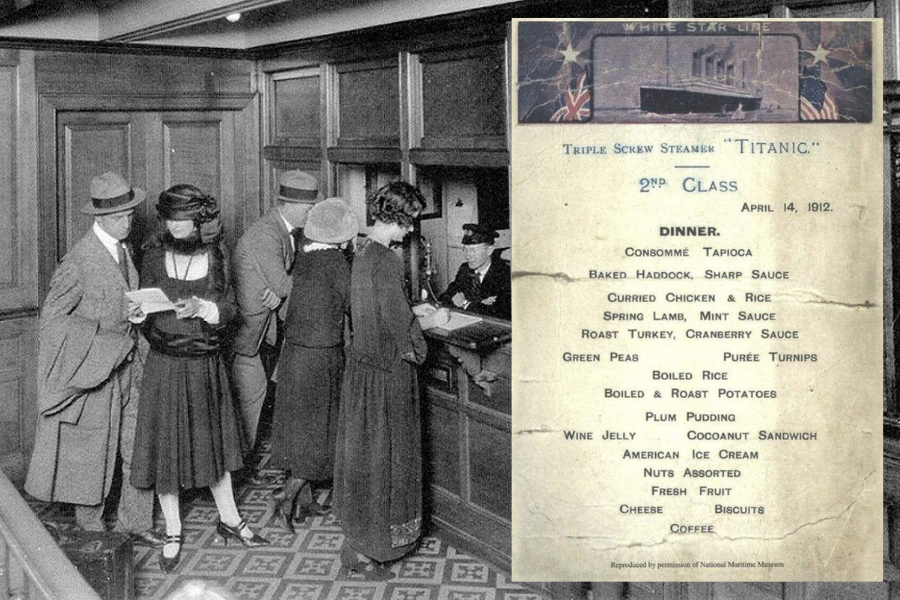

Second-class passengers aboard Titanic received a full dinner service with printed menus. On the evening of April 14, they were served roast turkey, spring lamb, boiled potatoes, and American-style ice cream—without knowing history was closing in.

The meals were served on porcelain, not tin. Waiters wore waistcoats. The dining saloon seated nearly 200 guests in a room designed to resemble a provincial English hotel.

Titanic researcher Paul Louden-Brown called second-class accommodations “the equivalent of first class on many other ships.” The menu confirms this. And the opening course set the tone for what followed.

Consommé Tapioca and Spring Lamb

The meal began with consommé tapioca—a clear beef broth with suspended tapioca pearls. A light, refined starter, it signaled an elevated dining experience even in second class.

Next came spring lamb with mint sauce. The lamb was likely roasted and sliced, served with potatoes and seasonal vegetables. The mint added a familiar, savory-sweet note.

Cooks followed port-loaded provisions, adjusting menus mid-voyage based on freshness. But the next course—roast turkey—promised a celebratory flourish no second-class traveler expected at sea.

Roast Turkey and Boiled Potatoes

Roast turkey with cranberry sauce, followed by both boiled and roasted potatoes. The pairing echoed festive meals familiar to British, Irish, and American passengers traveling in second class.

Turkey was a luxury on board—less common than beef or pork. Its presence on the menu suggests a celebratory spirit or perhaps a Sunday tradition carried into dining plans.

Records from Harland & Wolff show the Titanic carried over 1,100 pounds of poultry. It was divided between classes, with turkey considered one of the most prized second-class offerings.

Plum Pudding and Coconut Sandwiches

Second-class dessert included plum pudding—a steamed dish with dried fruit and spices, typically served warm with a sweet sauce. It was a traditional British offering with festive associations.

Also listed: coconut sandwich. Likely a layered confection of coconut and sponge cake, this dessert was simple but visually appealing, perhaps tinted with color to delight children and adults alike.

Lawrence Beesley, a second-class passenger and science teacher, later recalled the puddings and roasts as “well served and well cooked.” His memoir described the food with quiet approval.

American Ice Cream, British Pride

American-style ice cream appeared on the second-class menu, served with biscuits or jelly. Vanilla was the standard flavor, chilled in ice-packed barrels deep in the ship’s lower galley.

At the time, frozen desserts at sea were a novelty. Their presence in the second class suggested both innovation and a desire to offer guests something beyond standard expectations.

According to Titanic specialist Hugh Brewster, the White Star Line aimed to “impress all passengers, not just the wealthy.” The inclusion of ice cream illustrates that intention clearly.

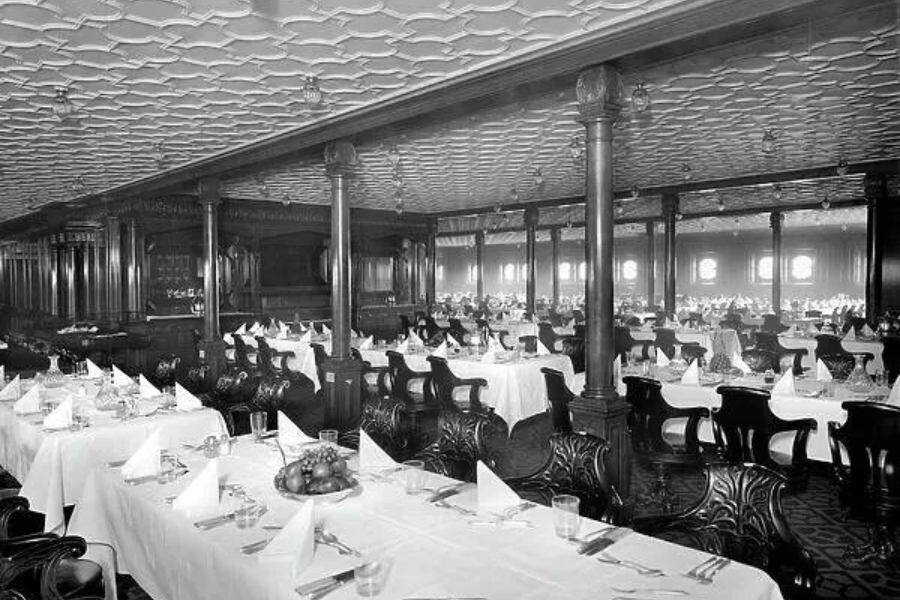

Inside the Second-Class Dining Saloon

The second-class dining saloon was lined with oak paneling and lit by electric lamps. It had its own dedicated kitchen and was praised for warmth, order, and cleanliness.

Photographs of the saloon show uniformed waiters and family groups seated at long tables. Meals were served in courses, with stewards trained to pace service carefully.

Titanic author J. Kent Layton describes the room as “quiet, dignified, and welcoming.” For many passengers, it was the most refined dining experience of their lives. But one deck above, eleven courses awaited beneath chandeliers—a final feast crafted for the most privileged few.

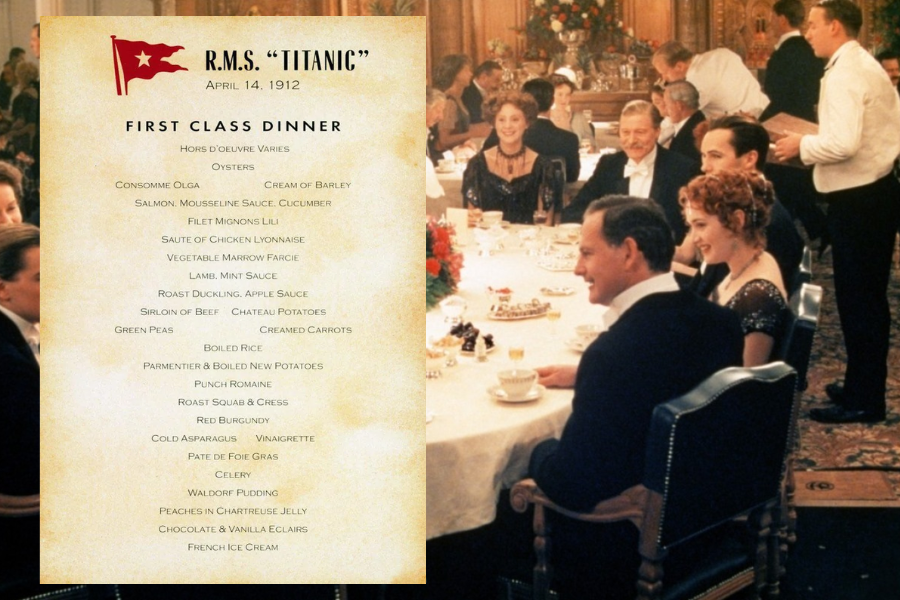

From Farm to First Class

First-class meals on the Titanic were elaborate, multi-course affairs influenced by continental cuisine. The menu for April 14 listed eleven courses, showcasing British ingredients prepared with French techniques.

Guests dined beneath crystal chandeliers on fine china. The food wasn’t merely nourishment—it was social theater. Dining offered status display, conversation, and a chance to observe or impress.

According to White Star Line documents, Titanic aimed to compete with the Ritz. Every element—from service to seasoning—was curated for passengers accustomed to luxury hotels and private estates, and the meal had only just begun.

First Class Hors d’oeuvres and Oysters

Dinner opened with hors d’oeuvres variés, likely including anchovies, olives, radishes, and pâté. It was designed to awaken the palate without overwhelming it.

Next came oysters—raw, freshly shucked, and served on crushed ice. Historical accounts identify them as Galway oysters, a popular delicacy among upper-class British diners.

Auctioned first-class menus confirm this pairing. According to Bonhams and Heritage Auctions, Titanic’s oysters were among the ship’s best-remembered opening dishes, mentioned in several survivor recollections and private logs.

Filet Mignon Lili and Sautéed Chicken Lyonnaise

Many of the entrées served on April 14 were preserved in a dinner menu recovered by survivor Abraham Lincoln Salomon—now a time-stained artifact from the Titanic’s final hours.

The entrée list featured filet mignon Lili—beef tenderloin topped with foie gras and black truffle, likely finished in Madeira sauce. It reflected French haute cuisine at sea.

Another option was sautéed chicken Lyonnaise, served over onions and potatoes. The entrées set the bar high—but the next course proved Titanic’s chefs knew how to elevate even vegetables.

Vegetable Marrow Farcie and Château Potatoes

For lighter fare, Titanic offered vegetable marrow farcie—stuffed squash filled with herbed breadcrumbs and vegetables. This vegetarian option was rare on Edwardian menus, but it’s thoughtfully included here.

Château potatoes accompanied many dishes. These small, barrel-shaped cuts were sautéed in butter, offering a crisp texture that paired well with meat, poultry, or vegetable-based entrées.

According to culinary historian Rick Rodgers, this potato preparation “reflected French training.” But even these refined sides were merely a pause before the meal’s most dazzling moment.

Punch Romaine

Midway through the meal came punch Romaine, a frozen sorbet of citrus and rum. It was intended to cleanse the palate before the final, richer courses resumed.

Served in glass stemware, it included shaved ice, lemon, orange juice, and champagne. The dish was both theatrical and refreshing—an interlude more common in luxury resorts.

Food writer Veronica Hinke describes Punch Romaine as the most memorable dish of the evening due to its elegance and timing. While the third-class passengers enjoyed their plum pudding, the wealthier guests were indulging in more luxurious fare.

Waldorf Pudding and Éclairs by Gaslight

Dessert featured Waldorf pudding—a baked custard with dried fruit and walnuts. It was followed by éclairs filled with vanilla or chocolate cream, piped fresh and finished with a glaze.

Lighting came from gas chandeliers and table lamps. The desserts were served alongside cheese, fruit, and coffee, extending the meal into conversation and music.

The Waldorf pudding recipe appears in Last Dinner on the Titanic by Archbold and McCauley, one of the few verified cookbooks based on the original documented menus.

Pâté de Foie Gras and Red Burgundy Toasts

Later in the meal, guests were served pâté de foie gras with toasted brioche. The pâté was rich, smooth, and associated with fine French dining and elite palates.

Wine flowed throughout dinner. Red Burgundy accompanied beef and duck courses, while white wines complemented seafood and poultry. Champagne appeared with both dessert and punch Romaine.

A wine list found in White Star Line archives confirms a cellar stocked with Moët & Chandon, Madeira, and Claret—luxuries reserved for Titanic’s highest-paying passengers.

Dining Like an Aristocrat

Dinner in first class lasted two to three hours. Guests changed into evening wear, and men were expected to wear tails. The meal was both traditional and a performance.

Stewards delivered dishes in synchronized waves. Each course was timed, cleared, and replaced with fresh utensils. This rhythm mirrored upscale European restaurants of the time.

Titanic author Dan Butler described the meal as “a social and culinary ritual.” And decades later, Hollywood tried to capture that grandeur on screen.

Leonardo, Kate, and the Dinner Scene

James Cameron’s 1997 film recreated Titanic’s first-class dinner using original menu details. The now-famous scene with Jack Dawson was informed by archival research and surviving menu cards.

Props included replicas of 1912-era crystal and cutlery. Dishes like filet mignon, punch Romaine, and éclairs were featured, confirming historical accuracy, not just visual storytelling.

Cameron’s team consulted Titanic historian Don Lynch. In interviews, Lynch said the goal was to portray “not just the disaster, but the lost elegance” of life aboard the ship.

Take After Take: Dining on Set

To bring that elegance to life, the actors actually ate those meals. Real oysters, real éclairs, and real punch Romaine were served—every detail matched the original menu.

Kate Winslet later revealed that multiple takes were grueling. The white gloves were hard to keep clean, and resetting delicate crystal and cutlery became a meticulous, hours-long process.

Each shot demanded perfect timing and identical motions. But that blockbuster moment was just a taste of reality. Beneath the saloons, the ship was not only keeping its guests afloat. It also carried…

The Real Titanic Kitchens

Over 6,000 tons of coal. And 176 firemen were working around the clock to keep the boilers running. Titanic’s galleys alone burned through four tons of coal each day, supplying heat for stoves, ovens, and hot water.

Over 60 staff handled food prep, service, and cleanup. Galley logs show daily outputs of soups, roasts, breads, and desserts scaled to feed more than 2,200 people.

Blueprints from Harland & Wolff confirm that the Titanic’s first-class kitchen extended across two decks. It included pastry ovens, roasting stations, cold storage, and meat lockers.

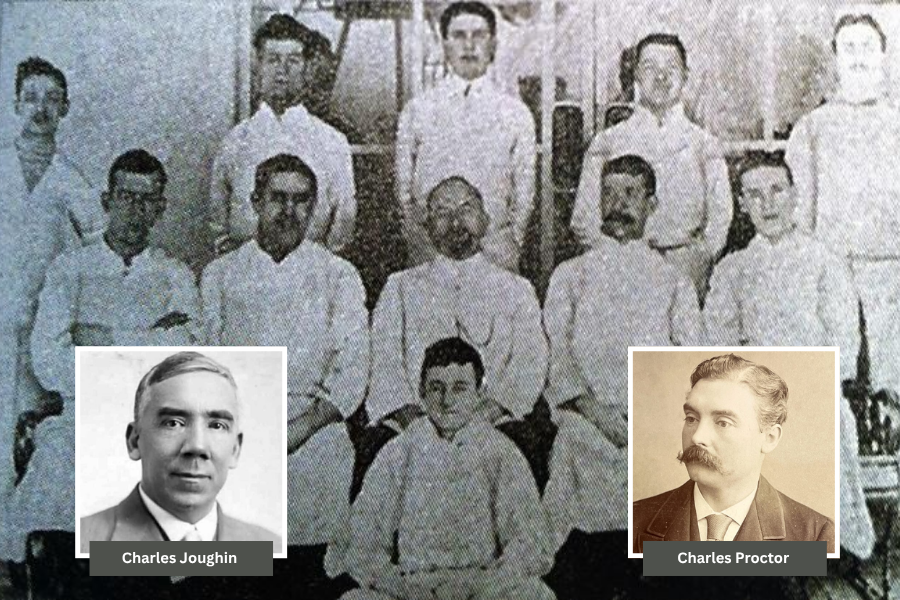

Meet the Chefs: Charles Proctor and Team

Charles Joughin was Titanic’s chief baker, but Charles Proctor oversaw the culinary team. Proctor had experience in high-end hotel kitchens and was responsible for menu planning and execution.

His team included pastry chefs, assistant cooks, butchers, bakers, and galley boys. Together, they prepared over 6,000 meals daily under time pressure and without modern refrigeration.

Most kitchen staff perished during the sinking. Joughin survived by clinging to an overturned lifeboat—later credited with staying calm, reportedly due to consuming bread and liquor before jumping in.

Feeding 2,200 Souls on a Floating Palace

Feeding 2,200 passengers required careful logistics. Titanic carried 75,000 pounds of meat, 11,000 pounds of fresh fish, and 40 tons of potatoes, loaded before departure from Southampton.

Menus were finalized before sailing, but adjusted depending on what remained in stock. Fresh ingredients were prioritized early in the voyage, while durable goods lasted longer.

Titanic’s bakery produced over 1,000 loaves of bread daily. A 1912 manifest listed eggs, dried fruit, and 800 bundles of asparagus—evidence of both volume and culinary intent.

Storing Food At Sea

Titanic carried no electric refrigeration but relied on cold chambers cooled by a powerful brine system and more than 100 tons of ice, loaded before departure in Southampton.

Insulated with cork and placed below the waterline, these rooms stored meat, fish, dairy, and produce. Crew monitored temperatures closely and rotated ice blocks daily to slow spoilage.

Perishables were served early in the voyage while cold storage was strongest. Logs show careful planning: meat in one hold, dairy in another—each compartment designed for maximum preservation efficiency.

Food as Identity

Dining aboard Titanic reflected more than taste—it reflected identity. Meal quality, service style, and available choices aligned closely with ticket class, reinforcing social and economic boundaries.

Third-class passengers dined communally. Second class followed a structured menu with waitstaff. First-class dining involved etiquette, wardrobe standards, and a full orchestra playing nearby during evening meals.

Historian Gareth Russell wrote, “The Titanic was a ship built on class,” and its menus serve as some of the clearest, most detailed evidence of that layered social structure.

The Stewards and the Service: Unsung Heroes

Titanic’s crew included over 400 stewards and stewardesses. Many worked in food service, memorizing passenger preferences and managing strict service timetables across all three class tiers.

These staff delivered meals, cleared dishes, served wine, and assisted elderly or unaccompanied travelers. In third class, they kept dining orderly and food flowing through crowded seatings.

The majority of stewards died in the sinking. Their names appear in crew logs and memorial records. Menus they distributed are now among the last surviving traces of their labor.

The Last Night

Dinner service concluded without incident. First-class guests lingered over wine and dessert, while second and third-class passengers had long since finished their simpler, earlier evening meals.

Galley crews began preparations for April 15 breakfast—scrubbing counters, rotating ice, and reviewing menus—unaware their kitchens would never reopen. The ship, for now, remained in quiet order.

Later, stewards found soup still warm on stovetops and bread ready for toasting. These unfinished preparations would become chilling evidence of a voyage halted mid-routine.

Midnight Iceberg, Interrupted Meals

At 11:40 PM, a sudden jolt ran through Titanic’s hull. A scraping sound followed. Most passengers assumed it was minor. No alarm. No panic. The ship barely seemed to shudder.

Below deck, the scullery had gone still. Above, a few guests were still sipping brandy or reading under gaslight, utterly unaware they’d just eaten their last meal alive.

Of the 2,240 people aboard, more than 1,500 would not survive. A first-class menu, later found in a survivor’s coat pocket, preserves a meal never cleared—a dinner paused beneath the sea.

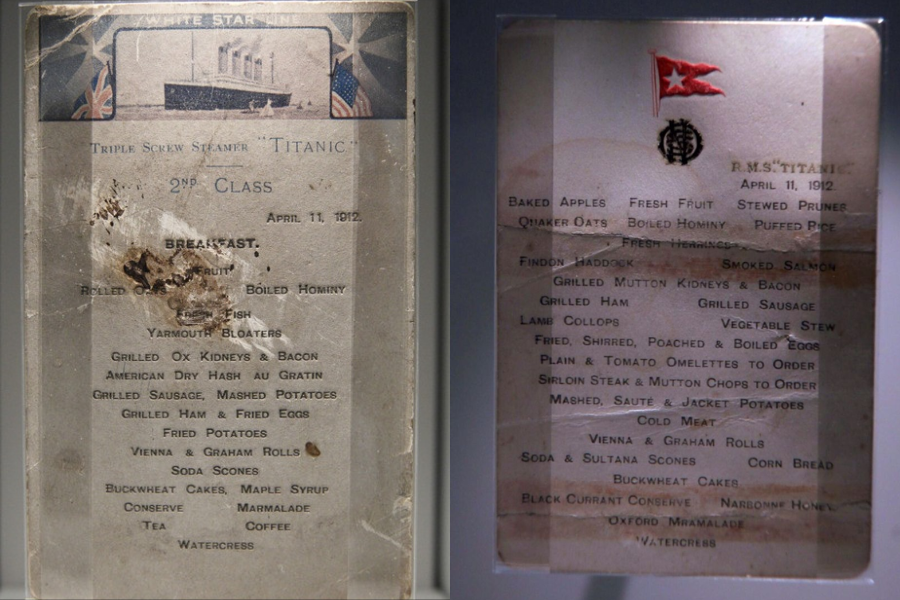

Menus Found in Pockets and Lifeboats

Titanic’s menus have become rare artifacts. One ‘April 14, 1912, first-class menu’ sold for $102,000 at a New York auction in 2012, according to Reuters and Heritage Auctions records.

Others reside in maritime museums in Belfast, Halifax, and Southampton. Displayed under glass, they are viewed not as dining lists, but as silent witnesses to a vanished world.

These menus weren’t designed to last. Printed daily, they were meant to be discarded. Their survival is due to chance, timing, and a few passengers’ instinct to save them.

Remnants of Elegant Dinners

After the sinking, divers and salvage teams discovered dining areas eerily intact. Tables were still set. Crockery lay undisturbed on silt-covered floors nearly two miles below the surface.

Among the artifacts: decanters, monogrammed cutlery, unopened bottles, and kitchen tools—all remnants of a meal prepared in full and left untouched as the ship broke apart.

According to the National Maritime Museum, these objects reflect “the final ordinary moments” before disaster. The meal became a memorial—each spoon and saucer carrying weight long after the plates went cold.

Remembering the Titanic Through Taste

The Titanic is remembered for its engineering, passengers, and tragedy. But its food—now fully documented—offers an intimate, human lens through which to understand the voyage.

We can now read what they read, eat what they ate, and imagine the conversations over consommé, pudding, or potatoes. It makes history personal and tangible.

This was the menu of the world’s most famous sea voyage—revealed more than a century later, one dish at a time, carrying the memory of those who never returned.