Bizarre and Delightful 19th-Century Recipes That Will Make You Appreciate Modern Cuisine

The 19th century was a time of culinary creativity, resourcefulness, and, let’s face it, some downright peculiar dishes. Without the convenience of modern appliances or a global pantry at their disposal, our ancestors concocted meals that might raise eyebrows (and stomachs) today. Let’s have a look!

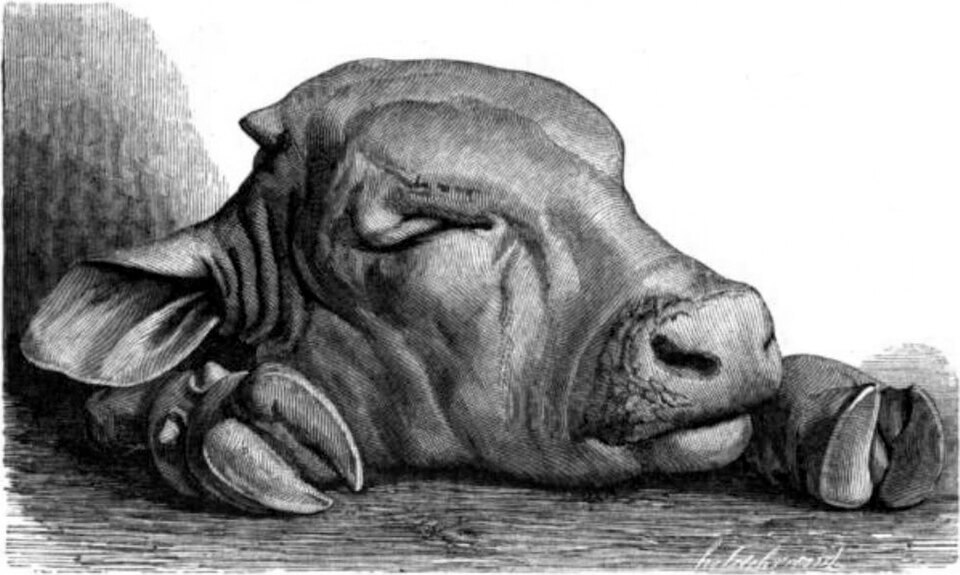

Boiled Calf’s Head

Nothing gets guests talking like a boiled calf’s head, tenderly cooked and placed on the table, its blank eyes silently questioning your life choices.

Victorian hosts, never ones to shy from flair, drenched the dish in “brain sauce”—a decadent gravy whipped up from the calf’s own brain matter.

This wasn’t just dinner; it was a flex. Serving this spectacle showed wealth, bravery, and culinary curiosity, assuming your guests could stomach their meal looking right back at them.

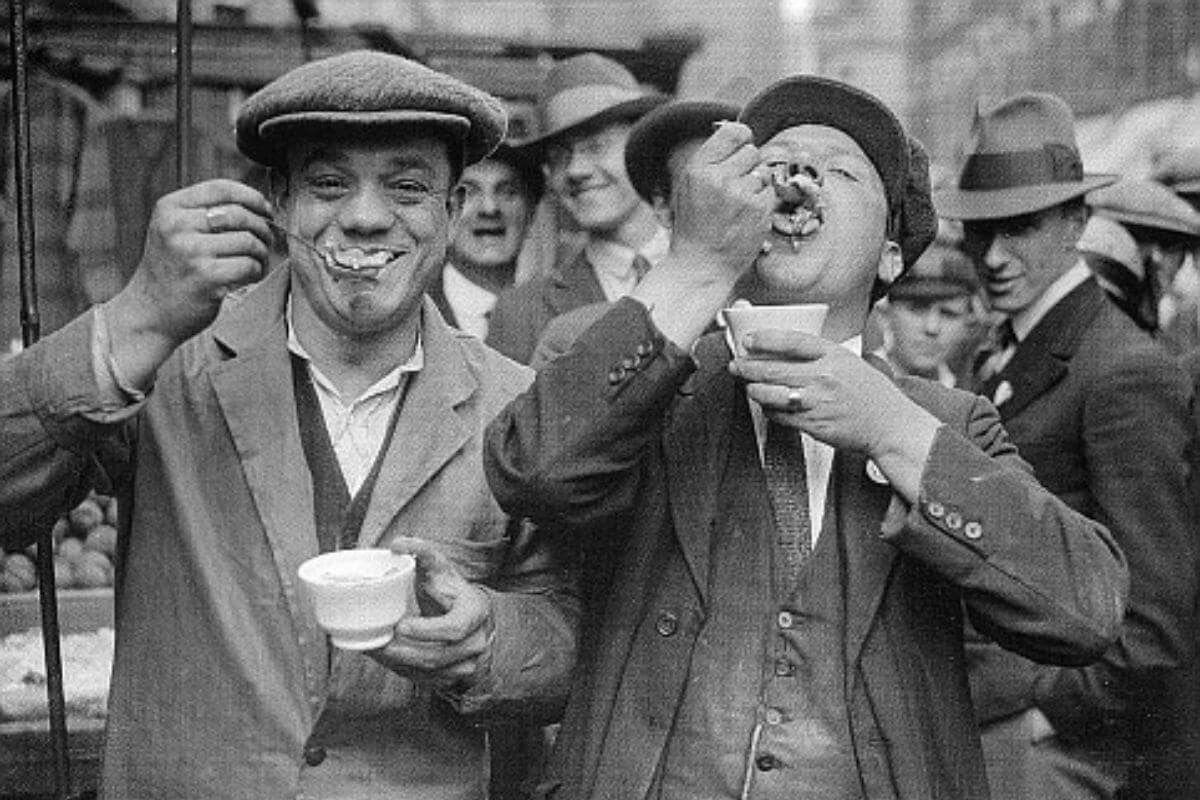

Jellied Eels

London’s East End thought, “What if our eels could also double as jelly?” So they boiled these slippery creatures and let them set into a wobbly delight.

Served cold, the dish proudly wiggled its way onto plates, giving diners the unique sensation of eating seafood-flavored gummy bears at Sunday lunch.

It was cheap, plentiful, and nutritious, proving once again that necessity really is the mother of some very questionable culinary inventions.

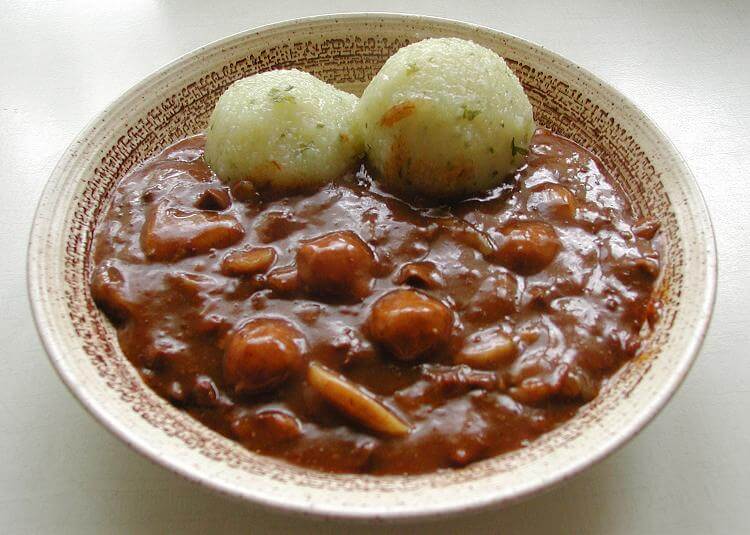

Mock Turtle Soup

When real turtles became a pricey delicacy, creative cooks turned to calf’s heads and feet to fake their way to a gourmet turtle experience.

The result? A thick, gelatinous soup that was oddly convincing, assuming you never actually tasted real turtle or valued culinary honesty.

Still, it became a beloved staple, turning deception into deliciousness, and making “mock” feel surprisingly authentic—at least by 19th-century standards.

Bedfordshire Clanger

Why bother with separate meals when you can slam dinner and dessert together in one hefty pastry? Enter the genius of the Bedfordshire Clanger.

One end was packed with savory meats, while the other was stuffed with sweet jam, effectively confusing your taste buds on purpose.

Perfect for workers with no time to spare, it was a culinary gamble: start your lunch, and by the end, surprise! Dessert awaits.

Hardtack

Soldiers and sailors relied on hardtack, those infamous flour-and-water biscuits harder than a week-old brick and with about as much flavor.

Nicknamed “molar breakers,” they could survive wars, long voyages, and probably small meteor impacts, making them the snack of survivalists everywhere.

Soaked in coffee or soup to avoid dental disasters, hardtack reminded everyone that sometimes, eating is more about endurance than enjoyment.

Hoecake

Forget fancy cookware—early Americans slapped cornmeal dough straight onto a garden hoe and roasted it over open flames like culinary pioneers.

The result was a rustic, crispy patty with enough grit to satisfy hunger and enough charm to become a southern staple.

Hoecakes were simple, hearty, and proof that necessity and laziness occasionally create surprisingly tasty results from whatever’s lying around the shed.

Hopping John

Black-eyed peas and rice might sound uninspired, but Southern cooks jazzed them up into Hopping John, a dish with more luck than flavor.

Tradition claimed it brought prosperity for the new year, though the true reward was surviving another bowl of peasant-level simplicity.

Salt pork or sausage added some flair, but at its heart, Hopping John remained a dish for the frugal, hungry optimist.

Boston Brown Bread

When you’re bored of baked bread, why not steam it? Boston Brown Bread did exactly that, turning humble grains into dense, hearty loaves.

Cornmeal, rye, and wheat combined in a molasses-sweetened batter, steamed for hours until it emerged as a pioneer’s version of cake.

Often served with baked beans, it was the carbohydrate bomb of choice for those brave enough to skip baking entirely.

Scrapple

This dish boldly answered the question, “What can we do with leftover pig parts?” by mixing pork scraps with cornmeal and frying it.

The loaf was sliced, pan-fried to crispy perfection, and enjoyed by anyone unfazed by its frank, no-waste origins.

Scrapple proved you could turn culinary scraps into something beloved, as long as you ignored what went into it in the first place.

Sally Lunn Bread

Rich, buttery, and wonderfully fluffy, this brioche-like bread bore the charming name of Sally Lunn, a baker whose existence remains questionable.

Despite the mystery, it became a teatime favorite, perfect for slathering with butter or jam and devoured in large, unapologetic bites.

Whether Sally Lunn was real or not, her namesake loaf carved a cozy spot in the carb-loving hearts of Victorian snackers.

Shoo Fly Pie

Molasses lovers rejoiced at this sticky-sweet pie, reportedly so sugary that flies had to be constantly shooed away mid-slice.

Crumbly topping and gooey filling made it irresistible, even if you risked a bug dive-bombing your dessert at any moment.

It doubled as both treat and activity: enjoy a slice, then enjoy the workout of defending it from airborne intruders.

Tomato Aspic

Because salads apparently weren’t exciting enough, Victorian cooks suspended vegetables in tomato-flavored gelatin for a dish that was both solid and suspicious.

The wobbly tomato mold took center stage at luncheons, its bizarre texture a conversation starter if not exactly a palate pleaser.

Cold, jiggly, and unmistakably strange, tomato aspic was a dish that begged the question: “Just because we can, does it mean we should?”

Oyster Ice Cream

An adventurous (read: mildly horrifying) blend of oysters, cream, and sugar, churned into frozen form to confuse and challenge even daring diners.

Allegedly enjoyed by First Lady Dolley Madison, proving once again that power and peculiar taste are eternal companions in culinary history.

Described by some as “briny custard,” oyster ice cream now lives in history’s vault of “let’s never do this again” experiments.

Beef Tea

Victorians swore by beef tea, a watery broth brewed from boiled beef, perfect for invalids, dieters, and anyone punishing their taste buds.

Served warm, it promised fortification with every thin sip, though flavor-seekers likely found it a deeply disappointing experience.

Still, it was considered a health tonic, which just goes to show: people will drink anything if they believe it’ll make them stronger.

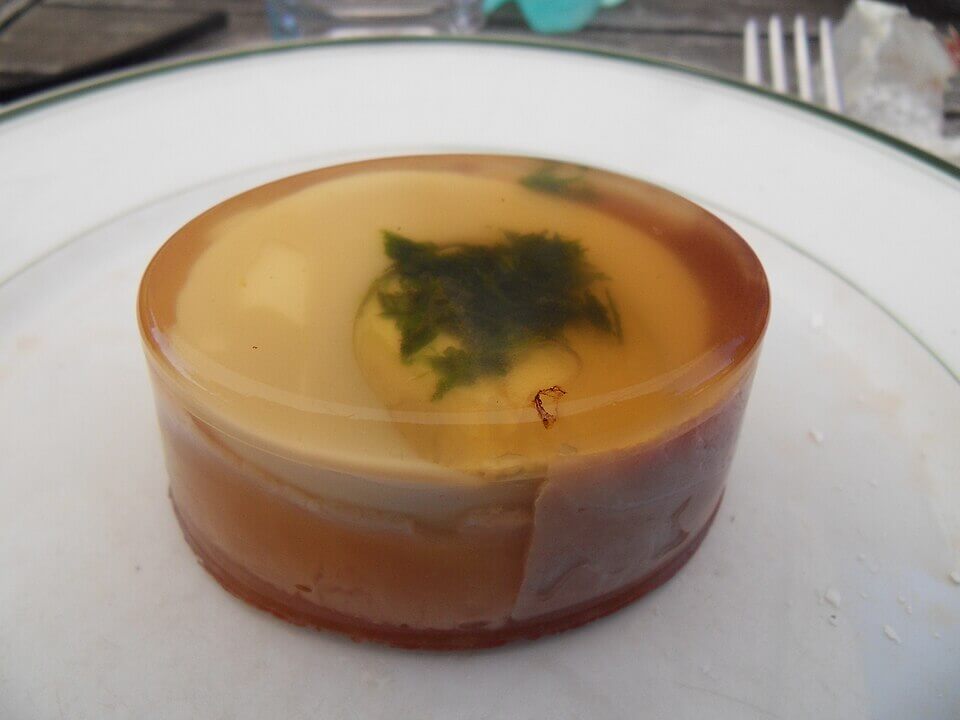

Calf’s Foot Jelly

Victorians couldn’t resist a good wobbly dessert, so they boiled calf’s feet to create gelatin, then added sugar and lemon for flair.

The resulting jelly proudly jiggled on every high-society table, its barnyard origins carefully ignored by dessert enthusiasts.

It was equal parts science experiment and sweet treat, and proof that early gelatin desserts were ambitious if not entirely appetizing.

Pigeon Pie

Forget chicken—Victorians looked to the skies and thought, “Let’s eat pigeons,” stuffing them into golden pies worthy of a countryside banquet.

Pigeon pie blended gamey bird flavor with rich gravy and buttery crust, making it a rustic favorite for hearty appetites.

More common than you’d expect, these pies fed families across Britain, despite the awkward mental image of munching on London’s park dwellers.

Beef Tongue

This dish did exactly what it said on the tin: cow tongue, boiled until tender, peeled, sliced, and served with great, chewy fanfare.

It was either enjoyed cold in sandwiches or hot with piquant sauces, for those brave enough to chew their way through.

Once considered elegant dining, beef tongue proves that when you cook it just right, even the cow’s loudest part becomes quiet perfection.

Cabbage Pudding

What’s better than cabbage? Obviously, cabbage mixed with suet and turned into a pudding, because vegetables and desserts should always mingle, apparently.

The result was a dense, savory dish, testing diners’ resolve as they worked through spoonfuls of leafy, fatty indulgence.

Served with pride, it showcased the era’s dedication to experimenting with suet, for better or (far more often) for worse.

Eel Pie

Just in case jellied eels weren’t adventurous enough, chefs lovingly encased those same slippery fish in a hot, flaky pastry.

Rich gravy joined the eels inside, creating a dish that was somehow both familiar and completely perplexing.

Popular at working-class gatherings, eel pie became a comfort food for anyone unfazed by its slimy star ingredient.

Liver Pudding

Take ground pork liver, add spices and cornmeal, then bake it into a loaf and serve proudly as a meaty, misunderstood pudding.

Don’t let the name fool you—this was no dessert, but a savory slab enjoyed fried and sizzling alongside breakfast eggs.

It stood as a testament to thrift and flavor, proving offal could absolutely be “awful good” when done right.

Pickled Walnuts

Victorians saw green, unripe walnuts and thought, “Let’s pickle these before they become actual nuts,” and thus a tangy treat was born.

Soaked in brine and vinegar, the pickled walnuts gained an earthy sharpness, perfect for accompanying roasts or pungent cheeses.

Their unique flavor wasn’t for everyone, but loyal fans loved the bold zing they brought to otherwise tame 19th-century tables.

Stewed Tripe

Cows’ stomach linings were cleaned meticulously before being stewed to a tender, almost sponge-like texture in brothy concoctions.

It was cheap, plentiful, and protein-rich, which made it a popular dish, especially among frugal home cooks.

Those with adventurous appetites appreciated its peculiar chew, while others just pretended not to know what they were eating.

Suet Pudding

Suet—glorious, artery-clogging beef fat—formed the heart of this dense, old-school pudding, fortified with flour and dried fruit.

Steamed for hours, it emerged as a heavy, humble dessert designed to stick to your ribs and test your cutlery.

Loved for its filling nature, suet pudding was less about light indulgence and more about enduring winter with stubborn, caloric determination.

Water Souchy

A thin, watery fish soup that somehow managed to underwhelm while still qualifying as sustenance in the eyes of 19th-century diners.

Usually served with white fish and a slice of bread, it offered modest nourishment with very little excitement.

If blandness had a culinary mascot, Water Souchy would proudly wave its flavorless flag for all the minimalist eaters out there.

White Soup

Made from veal stock, almonds, and cream, white soup was a pale but respectable option at refined dinner parties.

It wasn’t known for bold flavors, but its smooth, mild texture made it a safe, crowd-pleasing first course.

Think of it as the vanilla ice cream of 19th-century soups: simple, inoffensive, and completely forgettable.

Brown Windsor Soup

Rich and meaty, this thick brown soup became a royal favorite, especially loved by Queen Victoria for its hearty, satisfying warmth.

It packed beef and mutton into every spoonful, making it a staple of both palaces and common households alike.

Brown Windsor Soup proves that even royalty couldn’t resist a good, comforting bowl of meaty goodness on a dreary day.

Bubble and Squeak

A joyful mash-up of fried cabbage and potatoes, Bubble and Squeak got its name from the delightful sounds it made in the pan.

It was the ultimate leftover makeover, transforming scraps into a satisfying, golden-brown feast of crispy, greasy goodness.

Proof that in British cooking, even humble leftovers could rise to comforting, oddly charming culinary heights.

Cornbread and Salt Pork

Cornbread was the pioneer’s fluffy companion, a golden slab of comfort best served alongside thick, salty slices of pork that could outlast small plagues.

The pork, heavily salted for preservation, brought a mouth-puckering punch, perfectly offsetting the sweet, crumbly texture of fresh-baked cornbread.

Together, they created a duo beloved by frontier families everywhere, feeding hungry bellies and clogging arteries with rugged, pioneer-approved enthusiasm.

Baked Bean Sandwiches

Because baked beans weren’t messy enough, someone thought, “Let’s slap them between bread,” inventing this saucy, slippery, questionably portable culinary marvel.

Each bite was a gamble between enjoyment and bean escape, with rogue legumes launching themselves into laps across the nation.

Still, baked bean sandwiches delivered hearty satisfaction, ideal for those craving chaos and carbohydrates in every mouthful.

Mince Pie (Sweet, but Weird)

Traditionally packed with spiced fruits and, once upon a time, actual minced meat, this pie is basically holiday confusion in a flaky shell.

By the 1800s, the meat took a backseat, leaving sweetened fillings that still carried the dish’s savory roots like a culinary ghost.

It became a festive staple, baffling guests with its sweet-savory identity crisis, yet charming enough to win hearts by dessert.

Rook Pie

Tired of pigeons? Try rooks—another bird-based pie filling, popular in country kitchens where these black-feathered pests were conveniently plentiful.

Cooks claimed rooks tasted “like beefy chicken,” which sounds optimistic but, well, desperation breeds creativity on the dinner table.

Wrapped in pastry with rich gravy, rook pie turned pest control into a surprisingly edible, if slightly unsettling, family dinner.

Vinegar Pie

When life gave them no lemons, 19th-century bakers said, “No problem!” and turned to vinegar for tangy, pie-filling glory.

The result was surprisingly zesty, with vinegar mimicking citrus brightness in custard-like layers of sweet, sour confusion.

Penny-pinchers loved it, proving once again that frugality plus creativity often equals accidentally delicious historical oddities.

Blackberry Mush

An early ancestor to jam, blackberry mush combined berries, sugar, and water into a thick, spreadable paste perfect for slathering on anything.

Cooked down until sticky and fragrant, it doubled as both breakfast and dessert, because back then, sugar ruled every meal.

Simple yet delightful, it remains proof that sometimes, a little berry mush is all you really need to brighten the day.

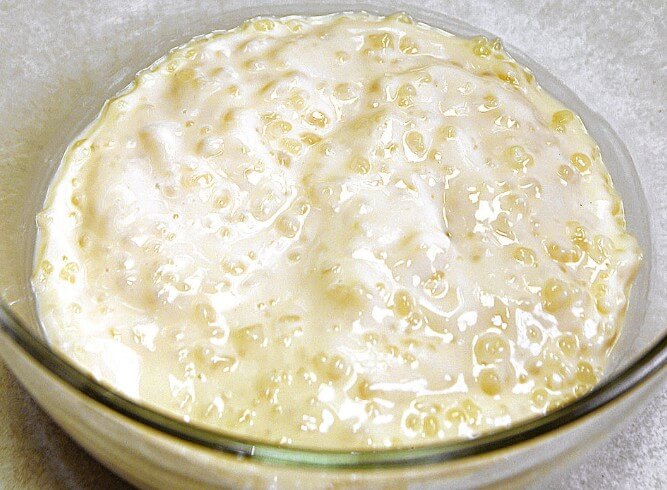

Hasty Pudding

Despite the name, making this cornmeal porridge wasn’t exactly a sprint, but it was still faster than most 19th-century kitchen escapades.

Cornmeal simmered in milk until thickened into a warm, filling mush, often sweetened with molasses or maple syrup for flair.

It was humble, dependable, and probably the culinary equivalent of an affectionate shrug from your grandmother.

Vinegar Lemonade

Citrus was pricey, so resourceful cooks faked lemonade with vinegar, sugar, and water—because thirst knows no budget constraints.

A few brave sips brought tangy refreshment, plus the existential question of why anyone drinks vinegar on purpose.

Surprisingly energizing, vinegar lemonade kept laborers hydrated and reminded them that taste is sometimes secondary to sheer hydration urgency.

Potato Candy

You read that right: sugar and mashed potatoes collided to create this bizarrely sweet, starchy candy treat.

The mild potato flavor vanished beneath mountains of powdered sugar, leaving chewy, sweet logs rolled in peanut butter or cocoa.

Kids adored it, and dentists probably wept quietly into their pillows at night, knowing what havoc it wreaked on tiny teeth.

Indian Pudding

Molasses and cornmeal joined forces to create this custardy, spiced dessert that was oddly comforting despite its less-than-glamorous appearance.

Baked slowly until set, it emerged sticky, brown, and humble, often served with a generous pour of cream or butter.

Indian pudding proved that ugly desserts can still win hearts, especially when they’re unapologetically sweet and warmly spiced.

Vinegar Taffy

Sugar shortages inspired inventive candy-makers to turn to vinegar, creating brittle, tangy taffy that confused and delighted young palates alike.

Sticky and sharp, it stuck to your teeth and taste buds, daring you to appreciate its unusual, puckering flavor.

Though not for the faint of heart, vinegar taffy taught kids early on that life is sometimes both sweet and sour.

Rabbit Fricassée

When beef or chicken felt too predictable, 19th-century chefs whipped up fricassée using tender, gamey rabbit, cooked in creamy white sauce.

Mildly exotic yet rustic, it fed families seeking variety without straying too far into culinary wilderness.

Served over biscuits or potatoes, it elevated rabbit from backyard critter to sophisticated table star—at least temporarily.

Stewed Squirrel

Frontier cooks saw opportunity in tree-dwellers, stewing squirrels with vegetables until tender, rustic perfection emerged from the bubbling pot.

Gamey but surprisingly rich, it warmed cold pioneers on bitter days, proving that survival meals could still feel like comfort food.

Stewed squirrel turned backyard pests into winter nourishment, redefining “locally sourced” with alarming efficiency.

Fried Beestings (Milk Pudding)

Beestings—milk from cows just after calving—was whisked with eggs and sugar, then fried into golden, custardy cakes.

Rich in natural creaminess, fried beestings felt like a decadent treat for those lucky enough to snag this fresh dairy delight.

The result was a cross between flan and French toast, bringing farmhouse indulgence straight to the breakfast table.

Mutton Broth

Mutton broth was the working person’s power drink, a bone-warming soup simmered with vegetables and tough cuts of sheep.

Fatty, flavorful, and sustaining, it powered laborers through grueling days with every steamy, slightly greasy sip.

Though humble, this dish packed surprising richness, proving that boiled bones can still make magic happen in a pot.

Rabbit Pie

Why stop at fricassée? Rabbit also found its way into golden pies, nestled in gravy beneath buttery, flaky crusts.

Hearty and warming, rabbit pie felt both rustic and refined, delighting hunters and kitchen table critics alike.

It was comfort food for countryside folk, turning wild game into a familiar, delicious family favorite.

Chicken Pudding

Yes, it’s real: tender chicken chunks baked into a savory, custard-like pudding with broth, butter, and biscuit dough.

The texture flirted between soufflé and meatloaf, confusing and satisfying diners in equal measure.

Chicken pudding was a showstopper at farmhouse gatherings, offering both novelty and hearty sustenance in one wobbly masterpiece.

Pemmican

A survivalist’s dream snack, pemmican combined dried meat, fat, and sometimes berries into a dense, calorie-packed puck.

Hard as a rock and nourishing as ten meals in one, it kept explorers alive during brutal expeditions.

Flavor came second to pure energy, making pemmican the ultimate no-frills endurance food for ambitious adventurers.

Boiled Onions

Simple yet strangely revered, whole onions were boiled until soft and buttery, transforming sharp bulbs into mellow, edible spheres.

Drenched in butter or cream, they offered a surprisingly sweet, mild experience far removed from their pungent raw selves.

Boiled onions graced many a table, providing budget-friendly flavor boosts to otherwise bleak meals.

Curd Fritters

Curds weren’t just for whey—19th-century cooks fried them into golden fritters, creating crispy shells with soft, cheesy interiors.

Sprinkled with sugar or drizzled in honey, curd fritters blurred the line between snack and dessert.

They were humble yet irresistible, proving that dairy and hot oil are always a winning combination.

Potato Biscuits

Fluffy yet earthy, potato biscuits brought mashed spuds into the baking world, adding moisture and heartiness to every tender bite.

They paired perfectly with butter or gravy, making them a farmhouse favorite for breakfast, lunch, and everything in between.

Potato biscuits were proof that carb-lovers always find ways to sneak in extra starch—deliciously so.

Gooseberry Fool

A deceptively simple dessert, gooseberry fool folded tart gooseberries into sweetened cream for a soft, tangy finish.

Served chilled, it provided welcome relief from heavier puddings, while still satisfying sweet cravings in a refreshingly light way.

Gooseberry fool earned its place at summer feasts, delivering a bright, cheerful end to any rustic meal.