Bizarre and Delightful 19th-Century Recipes That Will Make You Appreciate Modern Cuisine

The 19th century was a time of culinary creativity, resourcefulness, and, let’s face it, some downright peculiar dishes. Without the convenience of modern appliances or a global pantry at their disposal, our ancestors concocted meals that might raise eyebrows (and stomachs) today. Let’s have a look!

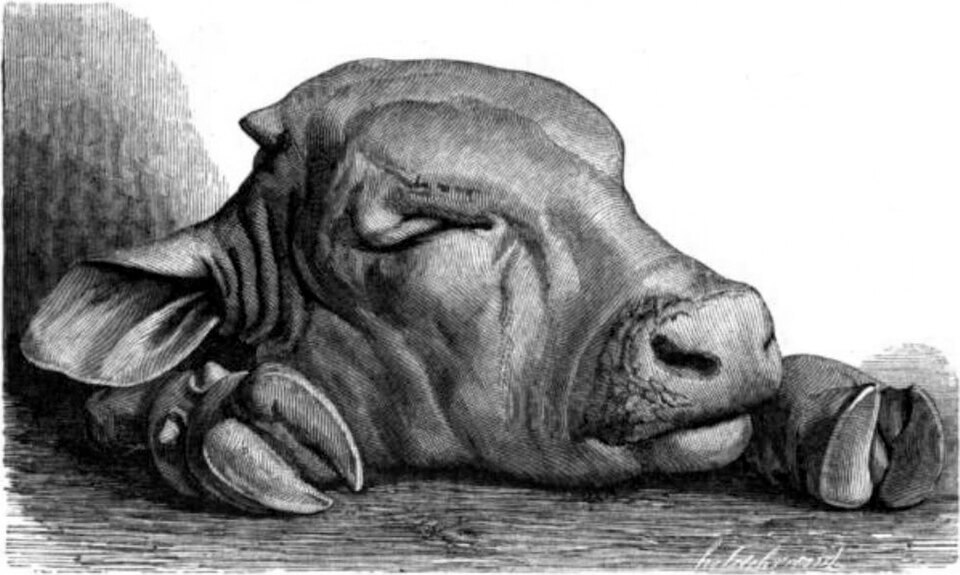

Boiled Calf’s Head

Nothing gets guests talking like a boiled calf’s head, tenderly cooked and placed on the table, its blank eyes silently questioning your life choices.

Victorian hosts, never ones to shy from flair, drenched the dish in “brain sauce”—a decadent gravy whipped up from the calf’s own brain matter.

This wasn’t just dinner; it was a flex. Serving this spectacle showed wealth, bravery, and culinary curiosity, assuming your guests could stomach their meal looking right back at them.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Boiled Calf’s Head wasn’t just about meat—it was about presentation. Diners would often serve it with the eyes intact, garnished with lemon slices in the sockets for extra flair.

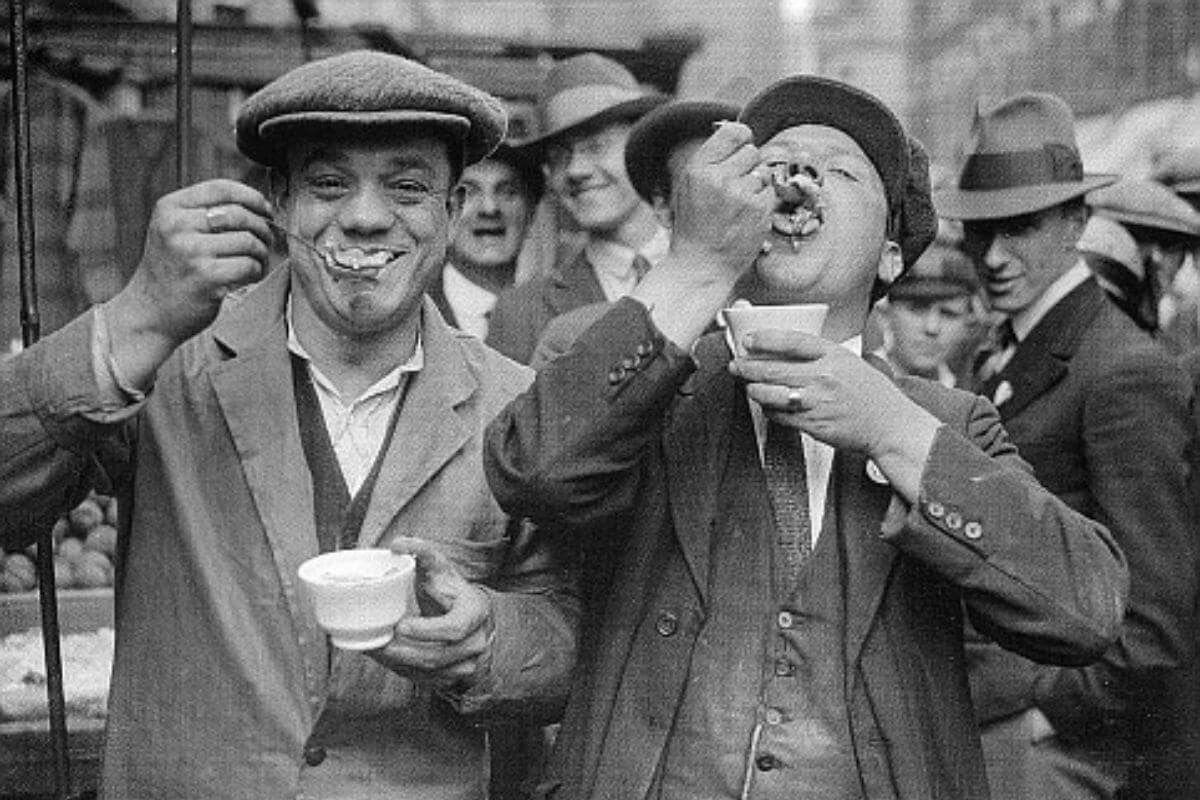

Jellied Eels

London’s East End thought, “What if our eels could also double as jelly?” So they boiled these slippery creatures and let them set into a wobbly delight.

Served cold, the dish proudly wiggled its way onto plates, giving diners the unique sensation of eating seafood-flavored gummy bears at Sunday lunch.

It was cheap, plentiful, and nutritious, proving once again that necessity really is the mother of some very questionable culinary inventions.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Fresh eels were often chopped while still alive and cooked immediately—so fresh, some diners claimed the eels would appear to “move” in the jelly after cooling. That’s one way to keep dinner lively.

Mock Turtle Soup

When real turtles became a pricey delicacy, creative cooks turned to calf’s heads and feet to fake their way to a gourmet turtle experience.

The result? A thick, gelatinous soup that was oddly convincing, assuming you never actually tasted real turtle or valued culinary honesty.

Still, it became a beloved staple, turning deception into deliciousness, and making “mock” feel surprisingly authentic—at least by 19th-century standards.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Inspired by the dish’s odd name, Lewis Carroll created the Mock Turtle character in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland—a sorrowful creature with a calf’s head, hooves, and tail.

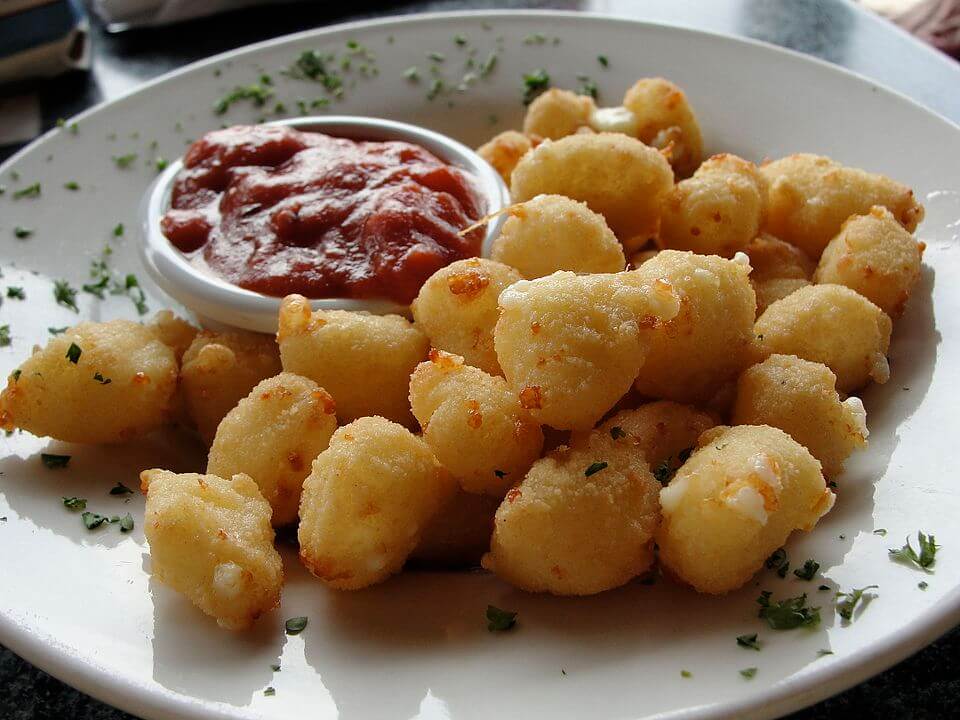

Bedfordshire Clanger

Why bother with separate meals when you can slam dinner and dessert together in one hefty pastry? Enter the genius of the Bedfordshire Clanger.

One end was packed with savory meats, while the other was stuffed with sweet jam, effectively confusing your taste buds on purpose.

Perfect for workers with no time to spare, it was a culinary gamble: start your lunch, and by the end, surprise! Dessert awaits.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Farm workers often warmed their clangers by laying them directly on a shovel over an open fire. The pastry crust kept the contents sealed and made reheating easy—even without a kitchen.

Hardtack

Soldiers and sailors relied on hardtack, those infamous flour-and-water biscuits harder than a week-old brick and with about as much flavor.

Nicknamed “molar breakers,” they could survive wars, long voyages, and probably small meteor impacts, making them the snack of survivalists everywhere.

Soaked in coffee or soup to avoid dental disasters, hardtack reminded everyone that sometimes, eating is more about endurance than enjoyment.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Hardtack had an incredible shelf life—some Civil War rations were reportedly still edible (if not enjoyable) 50 years later. Its survival power made it perfect for armies and ship crews.

Hoecake

Forget fancy cookware—early Americans slapped cornmeal dough straight onto a garden hoe and roasted it over open flames like culinary pioneers.

The result was a rustic, crispy patty with enough grit to satisfy hunger and enough charm to become a southern staple.

Hoecakes were simple, hearty, and proof that necessity and laziness occasionally create surprisingly tasty results from whatever’s lying around the shed.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

George Washington reportedly enjoyed hoecakes “swimming in butter and honey” as part of his regular breakfast. Rustic or refined, they earned a spot at even the most presidential tables.

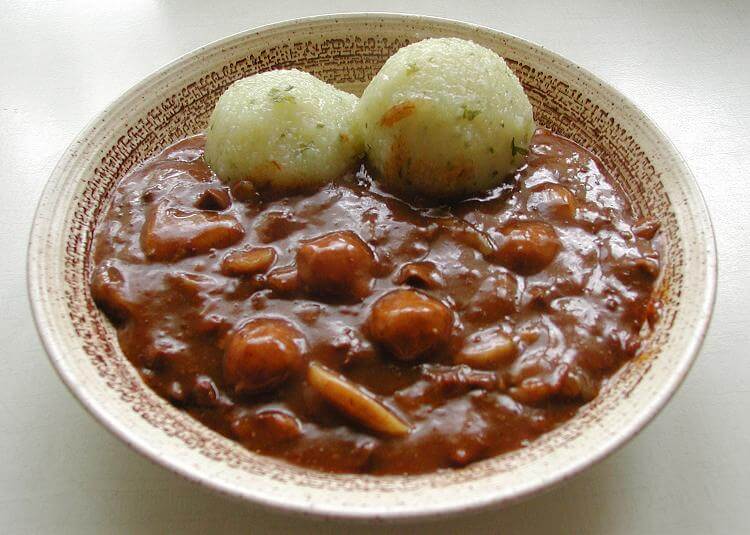

Hopping John

Black-eyed peas and rice might sound uninspired, but Southern cooks jazzed them up into Hopping John, a dish with more luck than flavor.

Tradition claimed it brought prosperity for the new year, though the true reward was surviving another bowl of peasant-level simplicity.

Salt pork or sausage added some flair, but at its heart, Hopping John remained a dish for the frugal, hungry optimist.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Traditionally eaten on New Year’s Day, Hoppin’ John was believed to bring wealth and prosperity—the black-eyed peas symbolized coins, and serving it with greens represented cash money.

Boston Brown Bread

When you’re bored of baked bread, why not steam it? Boston Brown Bread did exactly that, turning humble grains into dense, hearty loaves.

Cornmeal, rye, and wheat combined in a molasses-sweetened batter, steamed for hours until it emerged as a pioneer’s version of cake.

Often served with baked beans, it was the carbohydrate bomb of choice for those brave enough to skip baking entirely.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Early recipes often called it “Indian Bread” due to the use of “Indian meal” (cornmeal). These versions emphasized its Native American influences, fused with colonial resourcefulness.

Scrapple

This dish boldly answered the question, “What can we do with leftover pig parts?” by mixing pork scraps with cornmeal and frying it.

The loaf was sliced, pan-fried to crispy perfection, and enjoyed by anyone unfazed by its frank, no-waste origins.

Scrapple proved you could turn culinary scraps into something beloved, as long as you ignored what went into it in the first place.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Though of Germanic origin, scrapple became a hallmark of Pennsylvania Dutch cuisine in the 1800s. Their version was often seasoned with sage, thyme, black pepper, and marjoram for a herby finish.

Sally Lunn Bread

Rich, buttery, and wonderfully fluffy, this brioche-like bread bore the charming name of Sally Lunn, a baker whose existence remains questionable.

Despite the mystery, it became a teatime favorite, perfect for slathering with butter or jam and devoured in large, unapologetic bites.

Whether Sally Lunn was real or not, her namesake loaf carved a cozy spot in the carb-loving hearts of Victorian snackers.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Sally Lunn Bread is often linked to a Huguenot refugee named Solange Luyon who settled in Bath, England. The famed Sally Lunn Eating House claims to be the original bakery where the bun was sold. It’s now a restaurant and museum, where visitors can taste history.

Shoo Fly Pie

Molasses lovers rejoiced at this sticky-sweet pie, reportedly so sugary that flies had to be constantly shooed away mid-slice.

Crumbly topping and gooey filling made it irresistible, even if you risked a bug dive-bombing your dessert at any moment.

It doubled as both treat and activity: enjoy a slice, then enjoy the workout of defending it from airborne intruders.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

In the 19th century, Shoofly Pie was more breakfast than dessert—often served with strong black coffee to start the day. Sweet, sticky, and a far cry from modern granola.

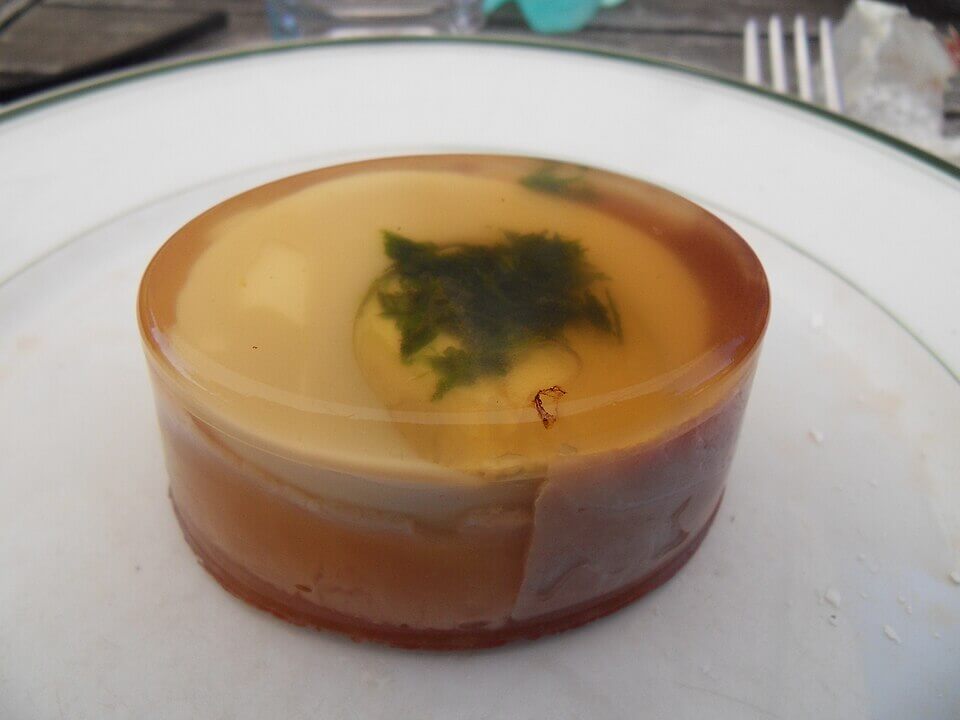

Tomato Aspic

Because salads apparently weren’t exciting enough, Victorian cooks suspended vegetables in tomato-flavored gelatin for a dish that was both solid and suspicious.

The wobbly tomato mold took center stage at luncheons, its bizarre texture a conversation starter if not exactly a palate pleaser.

Cold, jiggly, and unmistakably strange, tomato aspic was a dish that begged the question: “Just because we can, does it mean we should?”

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Tomato Aspic recipes often included Worcestershire sauce, hot pepper, celery, and vinegar, making it taste more like chilled tomato consommé than dessert. Some even added chopped green olives or shrimp.

Oyster Ice Cream

An adventurous (read: mildly horrifying) blend of oysters, cream, and sugar, churned into frozen form to confuse and challenge even daring diners.

Allegedly enjoyed by First Lady Dolley Madison, proving once again that power and peculiar taste are eternal companions in culinary history.

Described by some as “briny custard,” oyster ice cream now lives in history’s vault of “let’s never do this again” experiments.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Ice cream in the 19th century required hand-cranked churns and blocks of ice. Dishes like oyster ice cream signaled the host had access to expensive ice, fresh seafood, and kitchen staff.

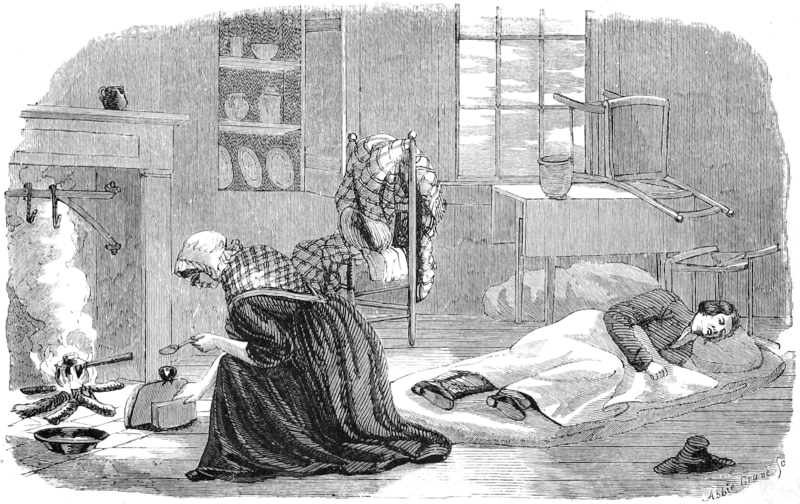

Beef Tea

Victorians swore by beef tea, a watery broth brewed from boiled beef, perfect for invalids, dieters, and anyone punishing their taste buds.

Served warm, it promised fortification with every thin sip, though flavor-seekers likely found it a deeply disappointing experience.

Still, it was considered a health tonic, which just goes to show: people will drink anything if they believe it’ll make them stronger.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

In Household Words, Charles Dickens praised beef tea’s “soothing properties” for the sick and melancholy. It even appears in his fiction, often served by kindly caregivers and concerned mothers.

Calf’s Foot Jelly

Victorians couldn’t resist a good wobbly dessert, so they boiled calf’s feet to create gelatin, then added sugar and lemon for flair.

The resulting jelly proudly jiggled on every high-society table, its barnyard origins carefully ignored by dessert enthusiasts.

It was equal parts science experiment and sweet treat, and proof that early gelatin desserts were ambitious if not entirely appetizing.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Rich in natural gelatin, Calf’s Foot Jelly was considered a nutrient-rich tonic for invalids. It appeared in medical cookbooks as a healing food for those recovering from illness, injury, or childbirth.

Pigeon Pie

Forget chicken—Victorians looked to the skies and thought, “Let’s eat pigeons,” stuffing them into golden pies worthy of a countryside banquet.

Pigeon pie blended gamey bird flavor with rich gravy and buttery crust, making it a rustic favorite for hearty appetites.

More common than you’d expect, these pies fed families across Britain, despite the awkward mental image of munching on London’s park dwellers.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

In grander versions, the pigeons’ legs were left sticking up through the crust as handles—or as a showy garnish. It was part practicality, part pageantry, and totally 19th-century dramatic dining.

Beef Tongue

This dish did exactly what it said on the tin: cow tongue, boiled until tender, peeled, sliced, and served with great, chewy fanfare.

It was either enjoyed cold in sandwiches or hot with piquant sauces, for those brave enough to chew their way through.

Once considered elegant dining, beef tongue proves that when you cook it just right, even the cow’s loudest part becomes quiet perfection.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Cooks had to boil the tongue for several hours, then peel off the thick skin before slicing. Labor-intensive, yes—but it rewarded them with tender, flavorful meat and a dramatic presentation.

Cabbage Pudding

What’s better than cabbage? Obviously, cabbage mixed with suet and turned into a pudding, because vegetables and desserts should always mingle, apparently.

The result was a dense, savory dish, testing diners’ resolve as they worked through spoonfuls of leafy, fatty indulgence.

Served with pride, it showcased the era’s dedication to experimenting with suet, for better or (far more often) for worse.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Cabbage pudding featured in 19th-century budget-friendly cookbooks like The Frugal Housewife, praised as a meatless, nourishing option for families. It was Victorian “meatless Monday” before the term existed.

Eel Pie

Just in case jellied eels weren’t adventurous enough, chefs lovingly encased those same slippery fish in a hot, flaky pastry.

Rich gravy joined the eels inside, creating a dish that was somehow both familiar and completely perplexing.

Popular at working-class gatherings, eel pie became a comfort food for anyone unfazed by its slimy star ingredient.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Eel Pie Island, in the River Thames, got its name from an old inn that served steaming eel pies to travelers. The island later became famous for jazz clubs and 1960s rock bands.

Liver Pudding

Take ground pork liver, add spices and cornmeal, then bake it into a loaf and serve proudly as a meaty, misunderstood pudding.

Don’t let the name fool you—this was no dessert, but a savory slab enjoyed fried and sizzling alongside breakfast eggs.

It stood as a testament to thrift and flavor, proving offal could absolutely be “awful good” when done right.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Despite sounding old-fashioned, liver pudding is still sold by regional meat producers in the American South. Brands like Neese’s and Gwaltney keep this old-world dish alive on modern shelves.

Pickled Walnuts

Victorians saw green, unripe walnuts and thought, “Let’s pickle these before they become actual nuts,” and thus a tangy treat was born.

Soaked in brine and vinegar, the pickled walnuts gained an earthy sharpness, perfect for accompanying roasts or pungent cheeses.

Their unique flavor wasn’t for everyone, but loyal fans loved the bold zing they brought to otherwise tame 19th-century tables.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Once pricked and soaked, the walnuts oxidize, turning a deep, inky black—a transformation that fascinated Victorian cooks and horrified first-time eaters. Also, it’s quite a long process. Traditional recipes called for two weeks of brining, followed by days of drying and months of pickling in spiced vinegar.

Stewed Tripe

Cows’ stomach linings were cleaned meticulously before being stewed to a tender, almost sponge-like texture in brothy concoctions.

It was cheap, plentiful, and protein-rich, which made it a popular dish, especially among frugal home cooks.

Those with adventurous appetites appreciated its peculiar chew, while others just pretended not to know what they were eating.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Victorian recipes often included instructions for bleaching tripe with vinegar or lemon juice to achieve a “clean and attractive” white hue—proving even stewed stomach had aesthetic standards.

Suet Pudding

Suet—glorious, artery-clogging beef fat—formed the heart of this dense, old-school pudding, fortified with flour and dried fruit.

Steamed for hours, it emerged as a heavy, humble dessert designed to stick to your ribs and test your cutlery.

Loved for its filling nature, suet pudding was less about light indulgence and more about enduring winter with stubborn, caloric determination.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Making a perfect suet pudding required skill. Victorian housewives were judged on their ability to make a pudding that was light, tender, and moist—not leaden, greasy, or overcooked.

Water Souchy

A thin, watery fish soup that somehow managed to underwhelm while still qualifying as sustenance in the eyes of 19th-century diners.

Usually served with white fish and a slice of bread, it offered modest nourishment with very little excitement.

If blandness had a culinary mascot, Water Souchy would proudly wave its flavorless flag for all the minimalist eaters out there.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

The name “Water Souchy” likely comes from the Dutch “waterzootje” or French “souché,” referring to boiled fish in broth. English kitchens adapted it into a simpler, gentler stew for home use.

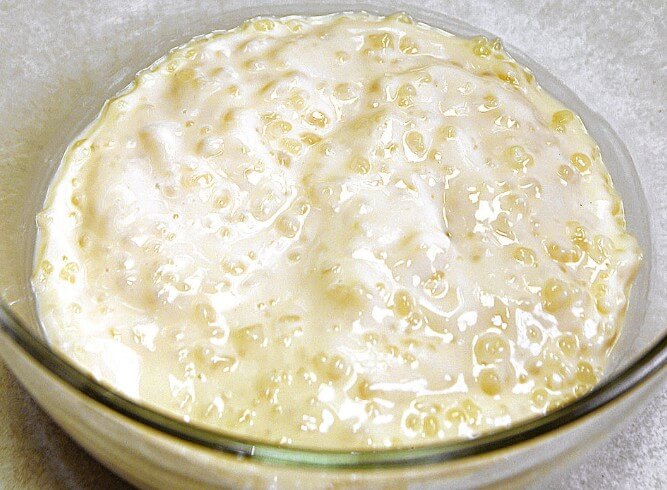

White Soup

Made from veal stock, almonds, and cream, white soup was a pale but respectable option at refined dinner parties.

It wasn’t known for bold flavors, but its smooth, mild texture made it a safe, crowd-pleasing first course.

Think of it as the vanilla ice cream of 19th-century soups: simple, inoffensive, and completely forgettable.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

White Soup was famously served at balls and banquets in Regency and Victorian England. In Pride and Prejudice, it’s the dish Mrs. Bennet stresses over preparing for a high-society gathering.

Brown Windsor Soup

Rich and meaty, this thick brown soup became a royal favorite, especially loved by Queen Victoria for its hearty, satisfying warmth.

It packed beef and mutton into every spoonful, making it a staple of both palaces and common households alike.

Brown Windsor Soup proves that even royalty couldn’t resist a good, comforting bowl of meaty goodness on a dreary day.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

By the 1960s and ’70s, Brown Windsor Soup had a reputation as the gray cardigan of cuisine—so overcooked and unappetizing it became a running joke in comedies and food columns.

Bubble and Squeak

A joyful mash-up of fried cabbage and potatoes, Bubble and Squeak got its name from the delightful sounds it made in the pan.

It was the ultimate leftover makeover, transforming scraps into a satisfying, golden-brown feast of crispy, greasy goodness.

Proof that in British cooking, even humble leftovers could rise to comforting, oddly charming culinary heights.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Victorian drinkers swore by Bubble and Squeak the morning after—a hot, greasy, salty dish to settle the stomach and revive the spirit. Today, it’s still beloved as a “morning-after” breakfast.

Cornbread and Salt Pork

Cornbread was the pioneer’s fluffy companion, a golden slab of comfort best served alongside thick, salty slices of pork that could outlast small plagues.

The pork, heavily salted for preservation, brought a mouth-puckering punch, perfectly offsetting the sweet, crumbly texture of fresh-baked cornbread.

Together, they created a duo beloved by frontier families everywhere, feeding hungry bellies and clogging arteries with rugged, pioneer-approved enthusiasm.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Cornbread and salt pork were standard rations for Union and Confederate troops alike. Soldiers fried salt pork into “sowbelly crisps” and soaked stale cornbread in coffee for portable meals on the march.

Baked Bean Sandwiches

Because baked beans weren’t messy enough, someone thought, “Let’s slap them between bread,” inventing this saucy, slippery, questionably portable culinary marvel.

Each bite was a gamble between enjoyment and bean escape, with rogue legumes launching themselves into laps across the nation.

Still, baked bean sandwiches delivered hearty satisfaction, ideal for those craving chaos and carbohydrates in every mouthful.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

In many 19th-century kitchens, slices of bread were buttered before the beans were added, enhancing richness and preventing sogginess—a practical trick that lives on in modern sandwich hacks.

Mince Pie (Sweet, but Weird)

Traditionally packed with spiced fruits and, once upon a time, actual minced meat, this pie is basically holiday confusion in a flaky shell.

By the 1800s, the meat took a backseat, leaving sweetened fillings that still carried the dish’s savory roots like a culinary ghost.

It became a festive staple, baffling guests with its sweet-savory identity crisis, yet charming enough to win hearts by dessert.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

In earlier centuries, mince pies were oblong to represent the manger, and were filled with 13 ingredients symbolizing Christ and the Apostles. By the 19th century, they had shrunk into the round individual pies we know today.

Rook Pie

Tired of pigeons? Try rooks—another bird-based pie filling, popular in country kitchens where these black-feathered birds were conveniently plentiful.

Cooks claimed rooks tasted “like beefy chicken,” which sounds optimistic but, well, desperation breeds creativity on the dinner table.

Wrapped in pastry with rich gravy, rook pie turned pest control into a surprisingly edible, if slightly unsettling, family dinner.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Rooks were considered agricultural pests, damaging crops and stealing grain. Turning them into food was both population control and rural economy at work—nothing went to waste in the 19th-century countryside.

Vinegar Pie

When life gave them no lemons, 19th-century bakers said, “No problem!” and turned to vinegar for tangy, pie-filling glory.

The result was surprisingly zesty, with vinegar mimicking citrus brightness in custard-like layers of sweet, sour confusion.

Penny-pinchers loved it, proving once again that frugality plus creativity often equals accidentally delicious historical oddities.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Despite its name, Vinegar Pie isn’t tart in a salad-dressing way. The vinegar simply brightens the rich custard filling, giving it a subtle zing, often balanced with nutmeg or cinnamon.

Blackberry Mush

An early ancestor to jam, blackberry mush combined berries, sugar, and water into a thick, spreadable paste perfect for slathering on anything.

Cooked down until sticky and fragrant, it doubled as both breakfast and dessert, because back then, sugar ruled every meal.

Simple yet delightful, it remains proof that sometimes, a little berry mush is all you really need to brighten the day.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Families often dried blackberries or used preserves in winter versions of the dish. Blackberry mush became a seasonless comfort, connecting harvest time with cold-weather survival.

Hasty Pudding

Despite the name, making this cornmeal porridge wasn’t exactly a sprint, but it was still faster than most 19th-century kitchen escapades.

Cornmeal simmered in milk until thickened into a warm, filling mush, often sweetened with molasses or maple syrup for flair.

It was humble, dependable, and probably the culinary equivalent of an affectionate shrug from your grandmother.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Hasty Pudding is immortalized in the Revolutionary-era tune “Yankee Doodle,” where the famously plumed rider “stuck a feather in his cap and called it macaroni”—but was also fond of Hasty Pudding.

Vinegar Lemonade

Citrus was pricey, so resourceful cooks faked lemonade with vinegar, sugar, and water—because thirst knows no budget constraints.

A few brave sips brought tangy refreshment, plus the existential question of why anyone drinks vinegar on purpose.

Surprisingly energizing, vinegar lemonade kept laborers hydrated and reminded them that taste is sometimes secondary to sheer hydration urgency.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Vinegar Lemonade (also called Haymaker’s Punch or Switchel) was served to farmers and fieldhands during long days of labor. With vinegar, molasses, water, and ginger, it replenished salts and quenched thirst like 1800s Gatorade.

Potato Candy

You read that right: sugar and mashed potatoes collided to create this bizarrely sweet, starchy candy treat.

The mild potato flavor vanished beneath mountains of powdered sugar, leaving chewy, sweet logs rolled in peanut butter or cocoa.

Kids adored it, and dentists probably wept quietly into their pillows at night, knowing what havoc it wreaked on tiny teeth.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Though odd at room temp, potato candy firmed up in the icebox, making it a cool, chewy treat that families kept wrapped in wax paper—ready to serve during holidays or Sunday visits.

Indian Pudding

Molasses and cornmeal joined forces to create this custardy, spiced dessert that was oddly comforting despite its less-than-glamorous appearance.

Baked slowly until set, it emerged sticky, brown, and humble, often served with a generous pour of cream or butter.

Indian pudding proved that ugly desserts can still win hearts, especially when they’re unapologetically sweet and warmly spiced.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Sugar was expensive in early America, so Indian Pudding relied on blackstrap molasses, giving it a dark color and rich, almost smoky flavor that no modern sugar can quite replicate.

Vinegar Taffy

Sugar shortages inspired inventive candy-makers to turn to vinegar, creating brittle, tangy taffy that confused and delighted young palates alike.

Sticky and sharp, it stuck to your teeth and taste buds, daring you to appreciate its unusual, puckering flavor.

Though not for the faint of heart, vinegar taffy taught kids early on that life is sometimes both sweet and sour.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Cooks dropped hot vinegar taffy into cold water to check for doneness—looking for the “hard ball” stage where it could be stretched, pulled, and eventually snapped like glass.

Rabbit Fricassée

When beef or chicken felt too predictable, 19th-century chefs whipped up fricassée using tender, gamey rabbit, cooked in creamy white sauce.

Mildly exotic yet rustic, it fed families seeking variety without straying too far into culinary wilderness.

Served over biscuits or potatoes, it elevated rabbit from backyard critter to sophisticated table star—at least temporarily.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

On farms and in gardens, rabbits were often shot for damaging crops—then quickly skinned, gutted, and turned into dinner. Fricassée was the civilized end to a very practical solution.

Stewed Squirrel

Frontier cooks saw opportunity in tree-dwellers, stewing squirrels with vegetables until tender, rustic perfection emerged from the bubbling pot.

Gamey but surprisingly rich, it warmed cold pioneers on bitter days, proving that survival meals could still feel like comfort food.

Stewed squirrel turned backyard pests into winter nourishment, redefining “locally sourced” with alarming efficiency.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Shooting squirrels was a rite of passage in rural America. With a small rifle and a pocket knife, young boys bagged their first game—then helped clean and stew it for supper.

Fried Beestings (Milk Pudding)

Beestings—milk from cows just after calving—was whisked with eggs and sugar, then fried into golden, custardy cakes.

Rich in natural creaminess, fried beestings felt like a decadent treat for those lucky enough to snag this fresh dairy delight.

The result was a cross between flan and French toast, bringing farmhouse indulgence straight to the breakfast table.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Beestings doesn’t need eggs or thickeners. Just baking or frying it transforms the liquid into a firm, jiggly pudding thanks to its natural richness and high casein levels.

Mutton Broth

Mutton broth was the working person’s power drink, a bone-warming soup simmered with vegetables and tough cuts of sheep.

Fatty, flavorful, and sustaining, it powered laborers through grueling days with every steamy, slightly greasy sip.

Though humble, this dish packed surprising richness, proving that boiled bones can still make magic happen in a pot.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

In the 19th century, doctors often prescribed mutton broth to convalescents and new mothers, praising it as easily digested, deeply nourishing, and rich in strength-building fat. Seasonings were also kept mild especially when served to the ill or elderly, whose systems required gentle care.

Rabbit Pie

Why stop at fricassée? Rabbit also found its way into golden pies, nestled in gravy beneath buttery, flaky crusts.

Hearty and warming, rabbit pie felt both rustic and refined, delighting hunters and kitchen table critics alike.

It was comfort food for countryside folk, turning wild game into a familiar, delicious family favorite.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Cooks often softened rabbit’s wild taste with parsley, thyme, or cream sauces, while richer versions added eggs or mushrooms to stretch and smooth the filling.

Chicken Pudding

Yes, it’s real: tender chicken chunks baked into a savory, custard-like pudding with broth, butter, and biscuit dough.

The texture flirted between soufflé and meatloaf, confusing and satisfying diners in equal measure.

Chicken pudding was a showstopper at farmhouse gatherings, offering both novelty and hearty sustenance in one wobbly masterpiece.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Once sliced, chicken pudding was served with melted butter, white sauce, or pan gravy poured on top—adding flavor and moisture to the dense, meaty slices.

Pemmican

A survivalist’s dream snack, pemmican combined dried meat, fat, and sometimes berries into a dense, calorie-packed puck.

Hard as a rock and nourishing as ten meals in one, it kept explorers alive during brutal expeditions.

Flavor came second to pure energy, making pemmican the ultimate no-frills endurance food for ambitious adventurers.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Pemmican’s mixture of fat and dried meat created a natural seal against air and bacteria, making it shelf-stable without salt or smoke. It was essential survival food for explorers in arctic and frontier regions.

Boiled Onions

Simple yet strangely revered, whole onions were boiled until soft and buttery, transforming sharp bulbs into mellow, edible spheres.

Drenched in butter or cream, they offered a surprisingly sweet, mild experience far removed from their pungent raw selves.

Boiled onions graced many a table, providing budget-friendly flavor boosts to otherwise bleak meals.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

To mellow sharpness, 19th-century cooks often boiled onions once, drained them, and boiled again before adding sauce. The result was ultra-mild, slightly sweet spheres of comfort food.

Curd Fritters

Curds weren’t just for whey—19th-century cooks fried them into golden fritters, creating crispy shells with soft, cheesy interiors.

Sprinkled with sugar or drizzled in honey, curd fritters blurred the line between snack and dessert.

They were humble yet irresistible, proving that dairy and hot oil are always a winning combination.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Before refrigeration, milk turned quickly. Rather than throw it away, families let it clabber naturally, strained the curds, and turned them into something rich, golden, and satisfying.

Potato Biscuits

Fluffy yet earthy, potato biscuits brought mashed spuds into the baking world, adding moisture and heartiness to every tender bite.

They paired perfectly with butter or gravy, making them a farmhouse favorite for breakfast, lunch, and everything in between.

Potato biscuits were proof that carb-lovers always find ways to sneak in extra starch—deliciously so.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

Potato biscuits used leftover mashed potatoes blended with flour, butter, and milk. The starch and moisture made them lighter, softer, and fluffier than ordinary flour-only biscuits.

Gooseberry Fool

A deceptively simple dessert, gooseberry fool folded tart gooseberries into sweetened cream for a soft, tangy finish.

Served chilled, it provided welcome relief from heavier puddings, while still satisfying sweet cravings in a refreshingly light way.

Gooseberry fool earned its place at summer feasts, delivering a bright, cheerful end to any rustic meal.

Did You Know? 🤓💡

The word fool likely comes from the French fouler, meaning “to mash” or “press.” Gooseberry Fool was made by gently folding stewed gooseberries into sweetened cream, creating a lush, silky treat.