Climber’s Life Was in His Best Friend’s Hands — What Happened Next Left People Furious

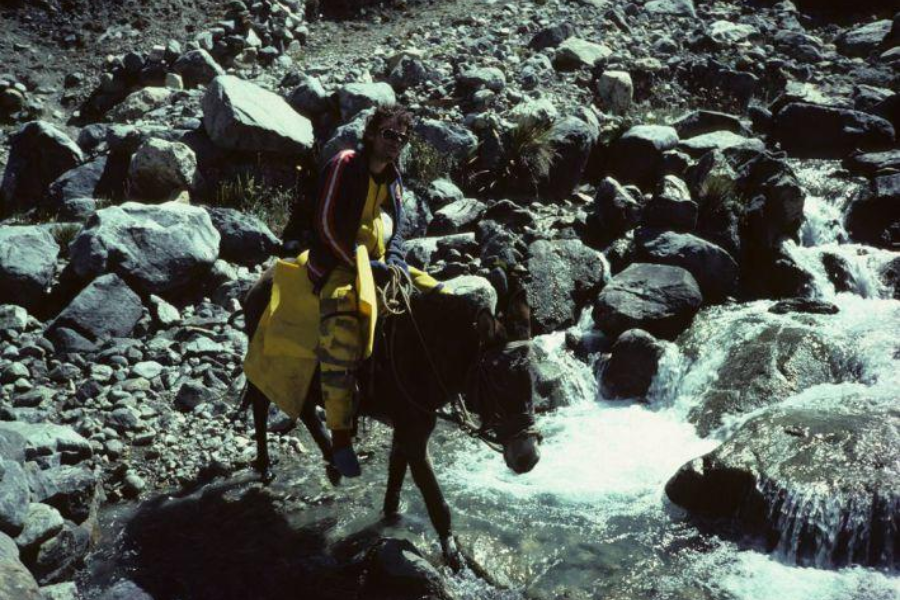

High on a frozen Peruvian peak in 1985, two young climbers were bound together by a single rope. When one slipped into the abyss, his partner faced the unthinkable choice. Exhausted, buried in snow, and convinced both would die if nothing changed, Simon Yates whispered into the wind, forcing himself to do what no climber ever wants to imagine.

A Wall No One Had Conquered

In the Andes of Peru rises Siula Grande, a vast face of rock and ice. At over six thousand meters, its West Face had never been climbed.

Others warned it was reckless. Too steep, too unstable, too deadly. But Joe Simpson and Simon Yates, young alpinists, wanted to be the first to prove it possible.

With ambition burning brighter than fear, they set off toward the mountain. They did not yet know how quickly triumph could turn into tragedy.

Youth Against the Impossible

It was June 1985. Joe was twenty-five, Simon just twenty-one. Both were young British climbers with years of experience in the Alps, but nothing could prepare them for the scale of the Andes.

They brought along Richard Hawking, less experienced, who would stay at base camp. His job was simple: wait, watch, and hope they returned alive.

For Joe and Simon, this was freedom. For Richard, it was uncertainty. And for all of them, the mountain promised only one thing—danger. How much risk could they endure?

Choosing the Hardest Way

They rejected fixed ropes, rejected supply camps. Their plan was alpine style—fast, light, all or nothing. One backpack each, no second chances, no way back down.

If they failed, there would be no rescue. The isolation of Siula Grande meant they were alone, with only each other to trust.

It was the boldest style—and the quickest way up the mountain. Every step locked them deeper into commitment. But what do you do when retreat is no longer possible?

The First Push Upward

The climb began with speed. On the first day, Joe and Simon gained three hundred meters. The wall seemed to open before them, but it would not last.

Higher up, the ice grew brittle. Avalanches slid down, unpredictable and constant. Every strike of the axe had to be exact. Every move could be their last.

They stopped at nightfall, cold and exhausted, yet hopeful—but the mountain was not finished tightening its grip, and their fragile luck was already beginning to fray.

The Price of Thirst

At altitude, dehydration comes fast. They needed four liters a day, but water came only by melting snow. And melting alone took hours. So, the boys drank far less than they should.

The dryness weakened them. Lips cracked. Muscles slowed. The effort of climbing became heavier with every breath. Yet the summit drew them higher still.

Every choice carried a cost. And their bodies were beginning to fail. Would thirst become the first enemy to kill their strength?

The Trap of Soft Snow

The last stretch of the wall was a nightmare. Snow was unstable, collapsing beneath their boots. It took six hours to move only sixty meters.

Avalanches swept past them, white rivers tearing down the slope. Each slide threatened to rip them from the mountain altogether.

As the light faded, they dug a hole in the snow for shelter, surviving one more night—yet the mountain waited, deciding how many more it would allow.

The Ridge of False Hope

Morning revealed the North Ridge. For a moment, the route looked easier. The slope was gentler, the horizon closer. Exhausted but determined, they pressed on.

Step after step, they gained ground. Their confidence returned. They believed the summit was within reach, that the worst was finally behind them.

On Siula Grande, nothing came easy; the ridge loomed ahead, promising either salvation or a trap more merciless than the wall they had left behind.

The Shadow of Descent

After hours of hacking through ice and battling thin air, they pressed upward, every muscle screaming. At last, they stood on the summit. Triumph. Victory. Against all odds, they had done what no one else had.

But the truth of mountaineering is cruel. Eighty percent of accidents happen not on the climb up, but on the way down.

Their moment of glory would last only seconds because the descent was about to begin. And the descent would destroy them.

The Whiteout

They expected the ridge to be simple. Instead, clouds rolled in, and snow swallowed every horizon. The mountain disappeared. They could not tell up from down.

Simon walked blindly, unaware that the ridge beneath him was hollow. The snow cracked, and he dropped into emptiness, buried in ice and fear.

He clawed back to the ridge, shaken but alive. But if the mountain could vanish once, what would happen when night fell again?

A Broken Sound

Exhaustion weighed heavily. Still, Joe pressed on, climbing a cliff. He planted his axe—but the sound was wrong, hollow, untrustworthy. The ice was thin.

Before he could correct, the wall gave way. He slipped. Agony shot through his leg, sharp and final. The bone had snapped. He felt it.

In the unforgiving world of alpine-style climbing, a broken leg was as good as a death warrant. But would Simon abandon him—or fight against the impossible?

The Unspoken Decision

Joe screamed, the mountain echoing his pain. Simon rushed to him. One look at the twisted limb told the truth: the climb was over.

He whispered the fear aloud: with a broken leg, he was finished. Simon said nothing, but his eyes held the same thought.

The rope between them was more than a lifeline now—it was a choice. Would Simon carry his partner’s fate, or let the mountain claim him?

The Code of Companions

Climbers live by a single code: never leave a partner behind. Simon could save himself. Or he could drag Joe down with him.

The wind howled around them, sharp as knives. Joe begged to continue. His pain was unbearable, but death by waiting was worse.

Simon chose. He would not abandon his friend. But could loyalty survive a mountain built to destroy them both?

Lowered Into Darkness

Simon dug his axe into the ridge, feeding rope through his frozen hands. Joe, hanging helplessly, was lowered slowly, his broken leg sending waves of agony through him.

The system worked, but it was brutal. Every section Simon lowered drained his strength, while Joe’s body dangled in silence, swinging dangerously with each shift of the storm.

Together they fought gravity, one rope-length at a time. Yet the mountain had no mercy. How long could Simon’s arms hold the weight of two lives?

The Invisible Drop

Snow thickened, masking the world in white. Simon, blind in the storm, lowered Joe again—never realizing he was feeding him directly into the mouth of the void.

Joe suddenly swung free, no rock, no snow beneath him. His broken body dangled over an unseen cliff, rope cutting into his waist with unrelenting force.

Suspended in the dark, Joe felt death waiting beneath his feet, while above him, Simon unknowingly lowered the rope, each movement bringing his partner closer to oblivion. He was running out of options.

A Deadly Standstill

The rope grew taut. Simon felt resistance but heard no signal. He tugged, desperate for Joe’s reply. Only silence returned, the storm swallowing every sound between them.

Time stretched unbearably. Simon braced himself against the snow, body screaming in pain, while Joe remained motionless, trapped in space, unable to climb with his shattered leg.

Simon’s strength bled away with every second. He had one option left, one that defied the code of alpinists. Could he bring himself to cut the rope?

The Cut

Simon’s arms shook violently. Snow collapsed around him, threatening to pull him from his stance. He realized he could no longer hold the rope without dying himself.

He fumbled in his pack, fingers numb, until he felt the blade. The decision came quickly, without ceremony. He slashed at the rope in the darkness.

Joe dropped instantly into the void. For Simon, silence replaced weight. For Joe, there was only the shock of falling into blackness that had no bottom.

Into the Crevasse

Joe crashed through fragile ice and plummeted into a hidden crevasse. The impact knocked the breath from him. Somehow, against all odds, he had not been killed.

He opened his eyes to total darkness, entombed in blue ice walls. The rope dangled uselessly above him, its severed end the proof of what Simon had done.

Alone, broken, trapped, Joe faced a chamber that seemed bottomless. If this was his grave, it was deeper and colder than he had ever imagined.

Simon’s Silence

On the ridge above, Simon collapsed into the snow, consumed by exhaustion and guilt. The knife was still in his hand, a reminder of the choice he made.

He dug a shallow hole for shelter, unable to move further. Every gust of wind seemed to whisper Joe’s name, reminding him of the friend he believed was gone.

Morning would come, and with it, descent. But Simon could not yet face the crevasse. He left behind the sound of Joe’s voice forever unanswered.

A Tomb of Ice

Joe turned off his headlamp, sinking into blackness. The silence pressed on him, heavy, absolute. His thoughts spiraled—better to die here than crawl endlessly in despair.

Minutes felt like hours. Madness brushed against him in the dark, twisting time. He switched the light back on, revealing nothing but frozen walls and endless depth.

He screamed Simon’s name until his throat tore raw. Only echoes replied. Yet somewhere inside, a refusal stirred. If this were his tomb, he would not stay buried. “If I were going to die, I wanted to do it in sunlight.”

The Bottom or the Exit

Joe searched the chamber with failing strength. A slanting wall tempted him to climb upward, but the broken leg made it impossible. Each attempt brought searing waves of pain.

Finally, he looked down. Far below, faint light flickered through a hole in the ice. It was impossibly small, but it was sunlight, and it meant survival.

He anchored himself with trembling hands and prepared to descend deeper into the unknown. To escape, he had to gamble everything on that single shard of light.

A Desperate Descent

Joe clipped the rope to his harness, lowering himself further into the crevasse. Each movement sent fire through his shattered leg, yet the light below kept him moving.

Ice cracked beneath his weight, threatening to collapse. He slid downward, breath ragged, fighting terror. The walls closed in, as if the mountain itself wanted him trapped forever.

Still, he reached the faint glow. The hole opened to daylight. But what waited beyond—a path to freedom, or another dead end?

Crawling Toward the Sun

He pushed through the opening and spilled out onto the glacier. The sudden brightness blinded him, dazzling after the darkness. For a moment, he felt reborn.

But the landscape stretched endlessly. Jagged ice, crevasses yawning on every side. His broken leg buckled beneath him, forcing him to crawl, dragging himself inch by inch across the wasteland.

The mountain had released him, but only into another prison. Could he crawl the kilometers back to camp before thirst, exhaustion, or madness overtook him?

Simon’s Return

Meanwhile, Simon descended the ridge alone, hollow with guilt. He replayed the cut rope in his mind, convincing himself Joe had died in the fall.

When he finally stumbled into base camp, Richard asked the question he dreaded: “Where’s Joe?” Simon’s reply was heavy, quiet—“He’s gone.”

Richard didn’t blame him. The mountain had claimed many. But out on the glacier, Joe was still alive—dragging himself slowly toward a camp that believed him lost.

Alone on the Glacier

Joe set small goals: crawl to a rock, rest, crawl to the next. His hands and knees shredded, his leg twisted, he inched forward across the vast ice.

Snow gave him sips of water, barely enough to survive. Every movement demanded more strength than he had, yet he refused to surrender his place to the mountain.

At night, the glacier echoed with creaks and groans. He pressed on, unaware that time was running out—not just for him, but for his rescuers as well.

The Vanishing Footprints

Joe found faint footprints pressed into the snow. Simon’s tracks. For a moment, hope surged—they could guide him back to camp, perhaps even to safety.

But sunlight erased them by morning, leaving him stranded again in a blank wilderness. He tried to follow memory instead, staggering in circles.

The path to survival was fading fast. Without direction, every step risked another crevasse. And somewhere, Richard was urging Simon that it was time to abandon camp.

Rocks and Ruin

The glacier ended, replaced by jagged rock. Crawling became impossible. Joe hauled himself upright, balancing on one leg, then fell. Each hop tore screams from his throat.

He left blood on the stones, collapsing often, dragging himself forward. The pain blurred into delirium, but he measured distance in meters, refusing to accept stillness as death.

Every fall risked shattering what remained of him. Yet through the agony, the faint image of a tent still lingered in his mind. Could he reach it?

A Camp Divided

Back at base camp, Richard grew restless. Days had passed without Joe. He urged Simon to pack up. The mountain had taken their friend; waiting longer meant danger.

Simon hesitated. His body was broken from the climb, his conscience heavier than his pack. The decision weighed—leave now, or risk one more day for a ghost.

As they debated, Joe crawled closer through the night. Each hour brought him nearer to camp, even as Simon and Richard prepared to abandon it forever.

Madness in the Night

Joe’s mind slipped in and out of reality. Shadows twisted into figures. He cursed the mountain aloud, then begged forgiveness. Hunger and thirst consumed the edges of thought.

The stars above spun in patterns he could not understand. Crawling in circles, he lost track of time, unsure if hours or days had already passed.

Then a familiar smell broke through the madness—something from campfire smoke drifting faintly in the air. His heart surged. Could safety be this close?

The End Game Begins

Joe’s body was wasted, his mind hollow. He believed he was crawling only to die, a final march toward nothing. The end felt certain, almost merciful.

Every movement burned. He debated whether to curl inside his sleeping bag, but feared he’d never rise again. The mountain was winning, and his body agreed.

Still, instinct carried him lower, dragging toward the riverbed where his corpse, at least, would be found. It was a dreadful plan—but it was all he had left.

A Foul Reminder

Crawling blindly, Joe stumbled into the latrine pit near their old campsite. Human filth smeared his body, the stench overwhelming, a humiliation almost worse than the pain.

But the stench shocked him awake, a brutal reminder that he was still alive. His senses cleared. The latrine meant he was close—closer than he had dared believe.

He lifted his head and searched the horizon. Something loomed ahead, red and yellow against the landscape. He thought it was a hallucination. Or maybe salvation.

The Dome in the Dark

What Joe saw appeared otherworldly: a red-and-yellow dome shimmering through exhaustion. He thought it might be a spaceship, a final trick of his mind before death.

Then beams of white light cut through the night. Voices followed—unmistakable, human. Among them, Simon’s. Joe’s heart lurched at the sound, proof that the nightmare had not swallowed him entirely.

He collapsed, unable to crawl farther. The dome was no illusion. It was their tent. Against every expectation, he had reached home ground before his body failed.

Voices in the Dark

Night fell as Joe reached the edge of camp. His voice cracked as he called for Simon, barely more than a hoarse whisper carried by the wind.

Richard stirred in his sleep, hearing noises outside. He dismissed them as animals moving across the glacier, nothing human. Exhaustion held him too tightly to rise and check.

But Simon woke. He knew the voice, impossible as it seemed. Against every belief he held, Joe Simpson was alive—calling from the darkness at their door.

The Impossible Sight

Simon rushed outside, disbelieving his ears. In the shadows, a figure crawled forward, face sunken, body broken. It was Joe—alive, against every law of the mountain.

Richard stared, unable to speak. Joe was barely human now, gaunt and bloodied, yet still dragging himself closer. His survival defied both logic and the silence of Siula Grande.

The nightmare of the climb had not ended with the cut rope. Now, they had to save a man who should not have survived at all.

A Body in Ruin

Joe had lost thirty-five percent of his body weight. His breath carried a sweet, chemical stench—the sign of ketoacidosis, starvation eating his muscles and organs from within.

Simon smelled it and understood instantly. Joe was dying, body consuming itself. They lacked medical tools, no drips or tubes, nothing to stabilize a man dissolving from the inside.

Improvised solutions existed, but they didn’t know them. Instead, all they could do was comfort him. For the first time, Joe stopped surviving and surrendered to their care.

The Long Ride Out

Barely conscious, Joe was strapped to a mule. For two days, they rode, every stumble slamming his broken leg, every jolt pulling him further toward collapse. Three men fought the mountain together again.

Then came 23 hours in the back of a pickup, rattling endlessly toward civilization. Simon refused to stop, terrified Joe’s body would give out before help arrived.

For Joe, the journey felt eternal. Eleven days after his leg broke, he finally reached a hospital bed, too exhausted even to comprehend that he had made it.

Lessons in Mortality

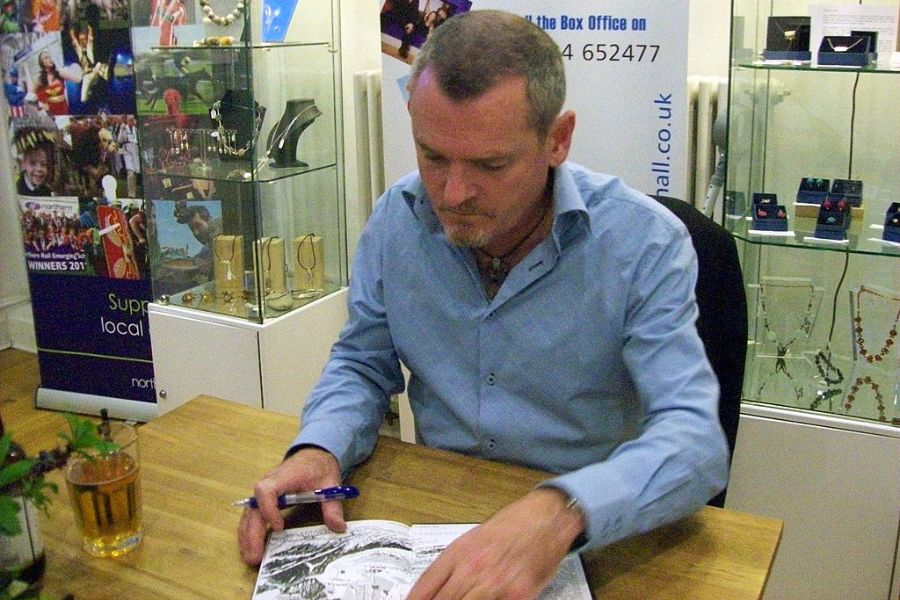

Years later, when interviewers asked Joe whether survival had changed him, he answered plainly: “All it taught me is that I don’t want to know my own death.”

He dismissed romantic notions of endurance. “I also learnt that Simon and I were bloody good mountaineers, because if we’d been bumbling amateurs we would not have got out of that shit.”

Survival had been skill, timing, and chance. For Joe, the life-altering experience made him understand survival in a totally different way, and some people may not agree with him.

Brutality of Survival

He reflected with stark honesty. “People have this idea of what survival is about, but the reality is that it’s brutal. You get destroyed on several levels.”

Then, he explained the paradox: you don’t only learn that you’re strong, but that you’re incredibly weak, too. Joe felt like he was breaking down all the time.

Finding Simon alive amid all those lows was a staggering surprise. For Simon, seeing Joe alive was the same. But in the years that followed, he carried the heavy weight of betrayal accusations.

Judgment and Misunderstanding

Public opinion turned harshly on Simon, as many outsiders condemned him for cutting the rope. “Afterwards, people decided Simon was in the wrong,” explained Joe, “but they had no understanding of what actually happened.”

Joe defended him, standing against the narrative. The world wanted heroes and villains. But to Joe, the truth was simpler: survival demanded choices others could never imagine.

The bond between them was forged in that decision. Joe carried no bitterness. The misunderstanding and guilt, however, followed Simon for years to come. And Joe felt the need to speak his truth through writing.

Survivor to Storyteller

Joe never expected anyone to care about his survival story. He only wanted to record the horrors he endured and the lessons he carried out of the Andes.

When he began writing, he worried readers might dismiss him as weak or selfish for admitting survival as it truly was—brutal, shattering, and far from romantic.

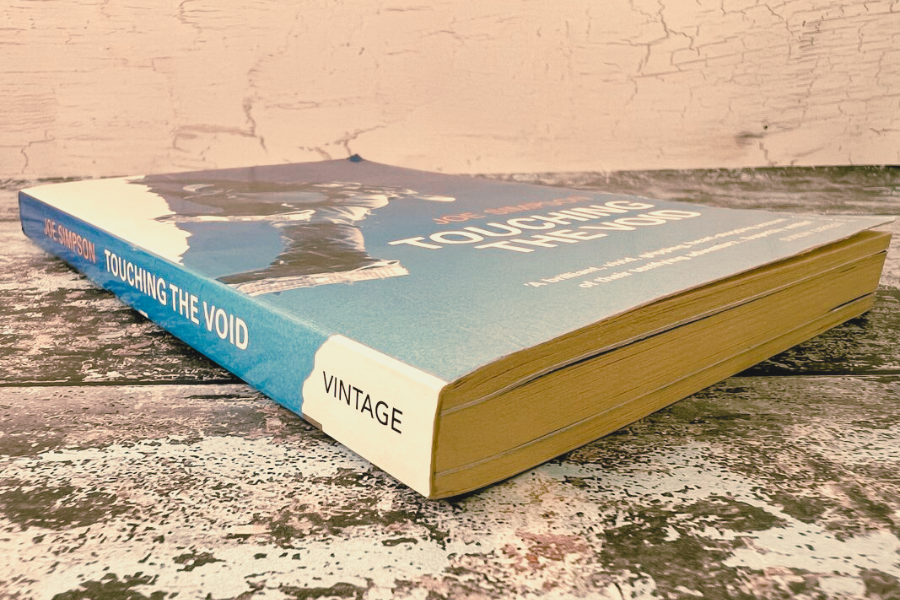

Instead, his manuscript—Touching the Void—was first embraced by climbers, then by audiences everywhere. Joe had no idea how far his story was about to travel.

A Book Beyond Expectation

Published in 1988, Touching the Void proved Joe’s doubts wrong from the start. He imagined selling a few hundred copies, mostly within the climbing community. “I thought maybe 500,” he recalled with understatement.

Instead, the book exploded. More than one million copies were sold worldwide, translated into dozens of languages, cementing its place as one of the greatest survival memoirs ever written.

What had begun as a tragedy became a livelihood. The book’s endurance proved that survival, told honestly and without romance, could captivate far beyond the mountaineering world. But pages weren’t enough. It had to be seen. To be recreated.

From Book to Screen

In 2003, Touching the Void became a film. Director Kevin Macdonald fused documentary interviews with harrowing recreations, creating a story as gripping on screen as it had been in print.

Joe admitted unease about reliving it. Watching actors stumble across glaciers and cut ropes reopened wounds, but also validated the reality of his ordeal. Audiences felt the tension as if they were climbing themselves.

The film won a BAFTA, earned critical acclaim, and went on to become the most successful documentary in British cinema history. It was so successful that later on, it was adapted to the stage.

Turning Pages into Performances

Scottish playwright David Greig adapted Touching the Void for the stage in 2018. The production used ropes, minimal sets, and light to recreate the mountain’s terrifying void in live performance.

Audiences gasped as actors dangled above the stage, bringing the ordeal into claustrophobic intimacy. The play proved survival could be as powerful on stage as on screen.

Later, the Melbourne Theatre Company revived the adaptation. They explored the truth behind the idea that mountaineering is a selfish pursuit. Is it though?

The Question of Selfishness

David Greig’s play didn’t only retell the climb; it added new voices. At Joe’s fictional funeral, Sarah, Joe’s sister, played by Lucy Durack, delivers a line that challenges the morality of mountaineering.

“I lost my moral compass. Do you happen to have one? Oh no, you’re a climber.” The audience laughed nervously, then fell silent. It cut too close to the truth.

The moment forced reflection: was the climb courage or selfishness? Do mountaineers risk lives for glory, or reveal something universal about human need to test limits? The debate still lingers. Joe was eager to give answers.

Ethics on the Edge

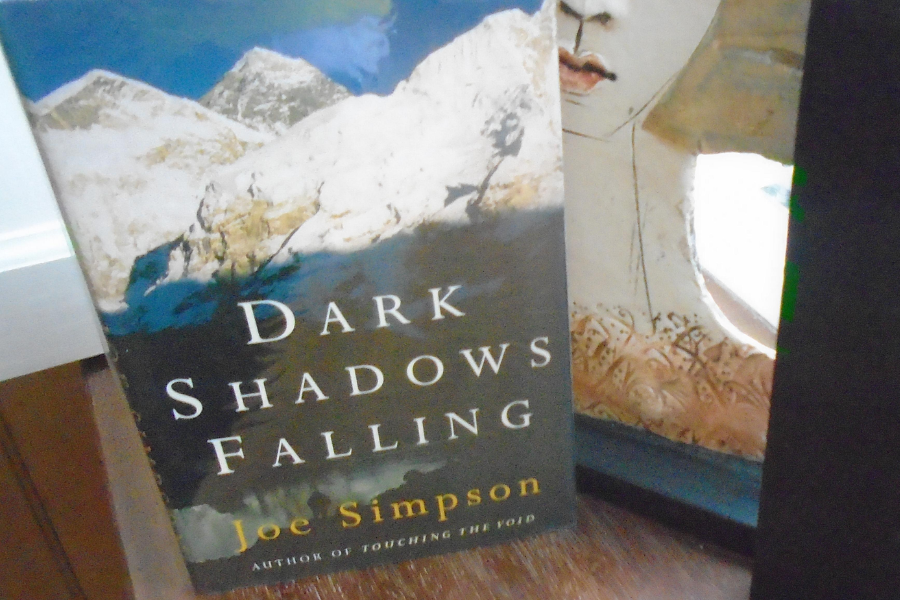

Joe has written five non-fiction books and two novels that all explore the ethics of climbing. His 1997 book Dark Shadows Falling was sparked by a tragedy on Everest that haunted him deeply.

“One of the climbers said there is no morality above 1,000 metres and I got absolutely bloody livid at that,” Joe recalled, his voice still edged with anger.

He dismissed the idea that summits came before humanity. “The very least you do is you sit with that man, you hold his hand, and you give him water.” Joe, who stopped being religious at a young age, also found a new meaning in life.

Spirit in the Heights

Beyond ethics, Joe reflected on what climbing meant spiritually. In This Game of Ghosts, he traced its roots back to childhood, “Suddenly torn away from your parents. Maybe it enables you to be more independent.”

He rejected Catholicism at fifteen, but found a different faith in the mountains. “At high altitude, you’re looking at light from stars that stopped existing 100,000 years ago. That kind of spirituality is your part of being Gaia.”

But no starlight could erase the memory of the knife slicing through rope. The act has lived ever since in a space between betrayal and necessity, a wound so deep it dares you to ask: in that frozen silence, would you have cut the rope too?