Rare 113-Year-Old Titanic Menu Surfaces, Reveals the Elaborate Final Meal Passengers Never Finished

They didn’t know it would be their last dinner. On April 14, 1912, over 2,200 passengers aboard the Titanic sat down to eat, some beneath crystal chandeliers, others at plain wooden tables. The menus from that final day have survived—pulled from pockets, preserved in museums, auctioned for thousands. Now, more than a century later, we can see exactly what they ate before the ship went down. This is the story of the Titanic’s last feast.

The Last Full Day at Sea

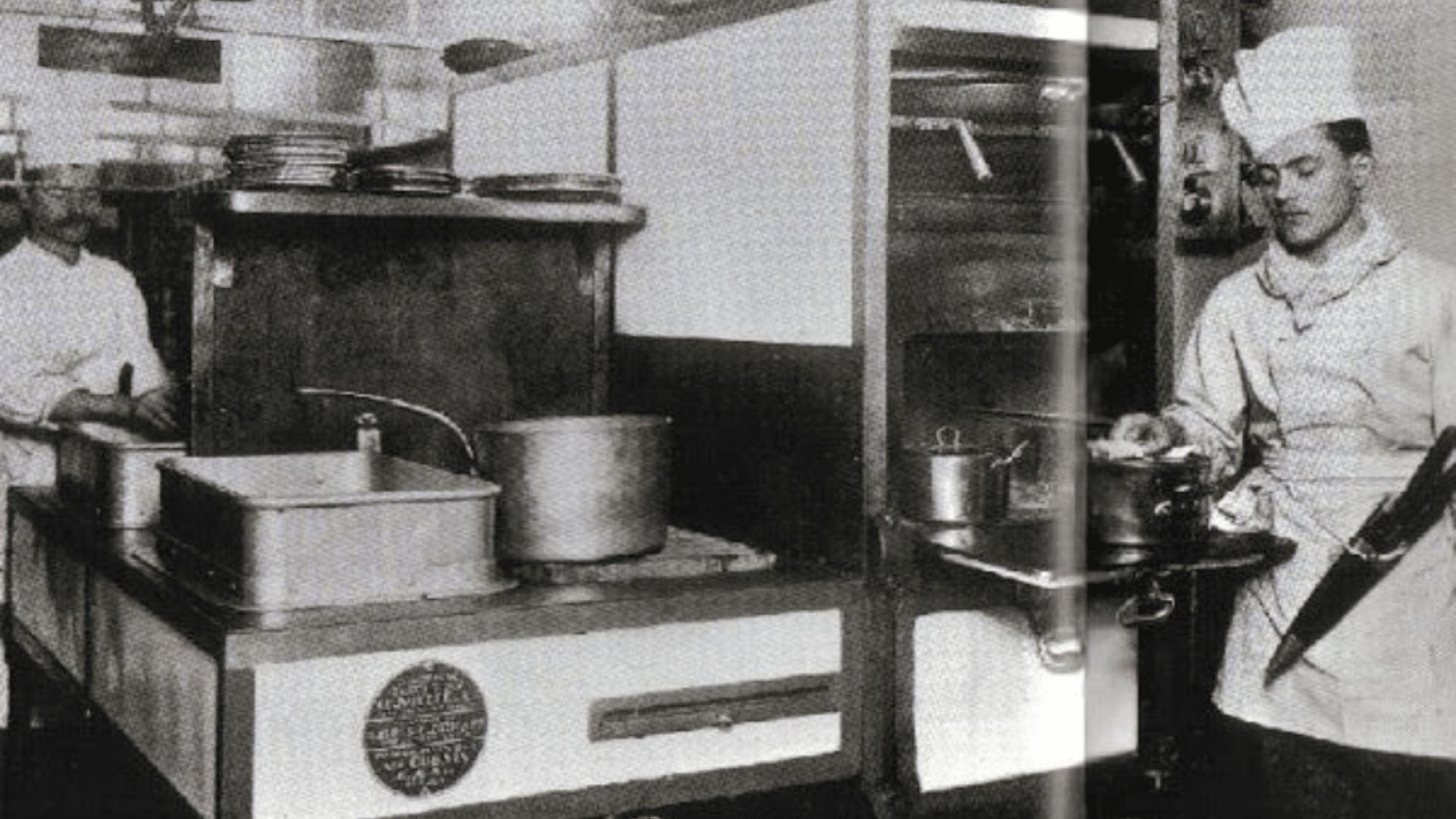

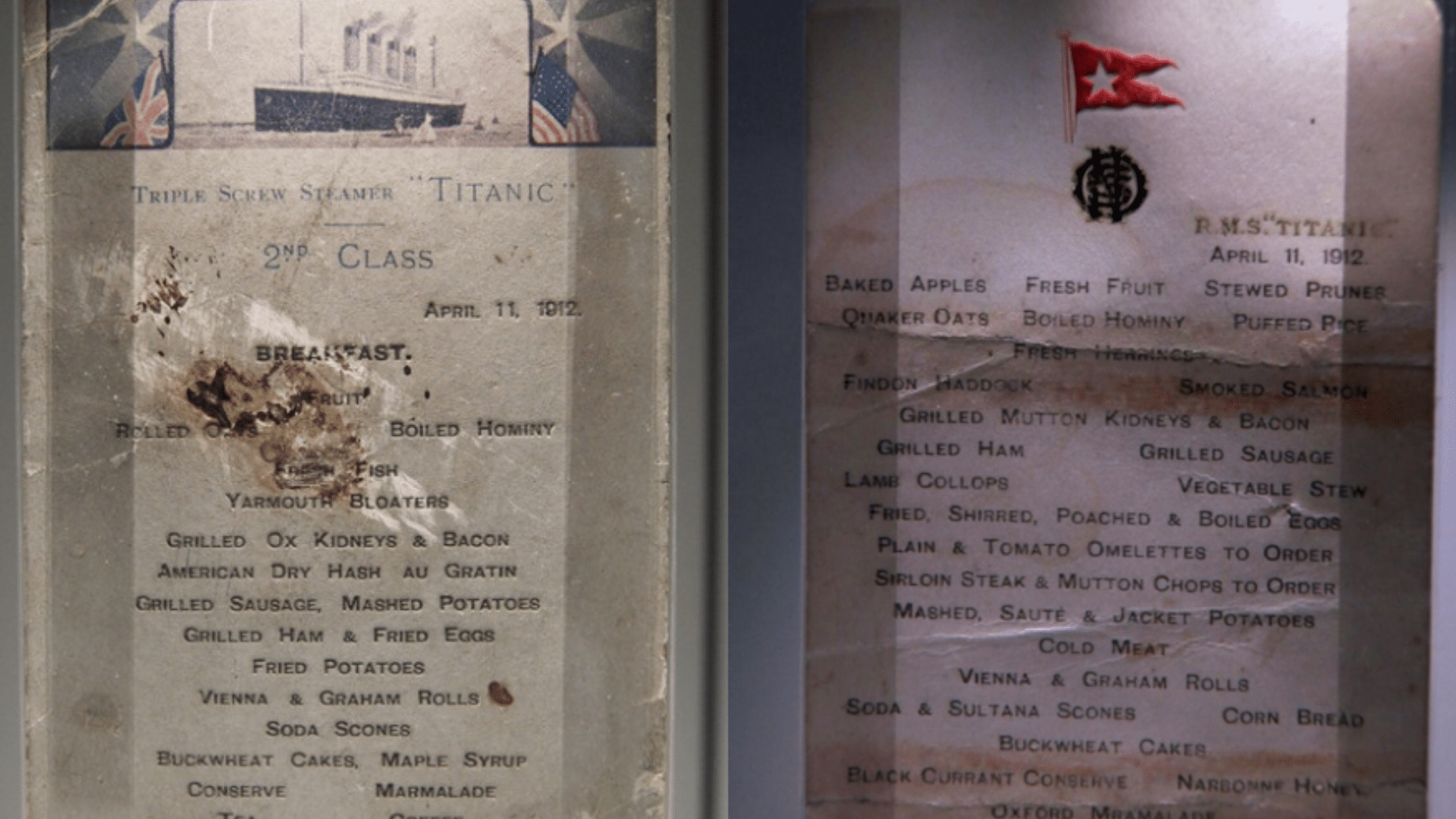

By Sunday morning, April 14, the Titanic had been at sea for 4 days. The ship was deep into its voyage from Southampton to New York. Over 60 cooks worked below deck, preparing thousands of meals daily. Freshly printed menus were delivered to passengers across all three classes. No one suspected these would be the final menus ever served. The scent of baking bread drifted through the corridors as the ship glided toward disaster.

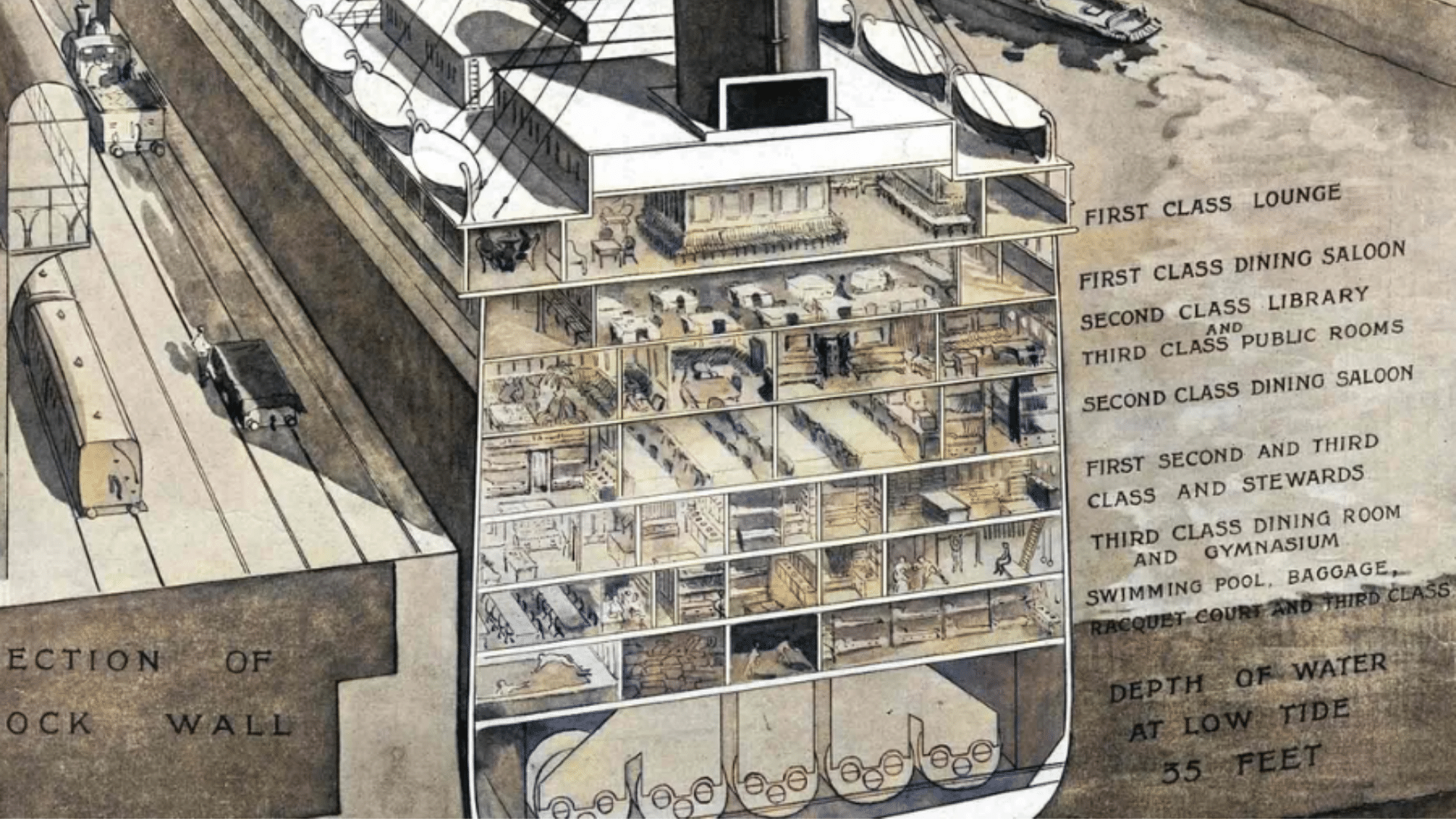

Three Classes, Three Different Worlds

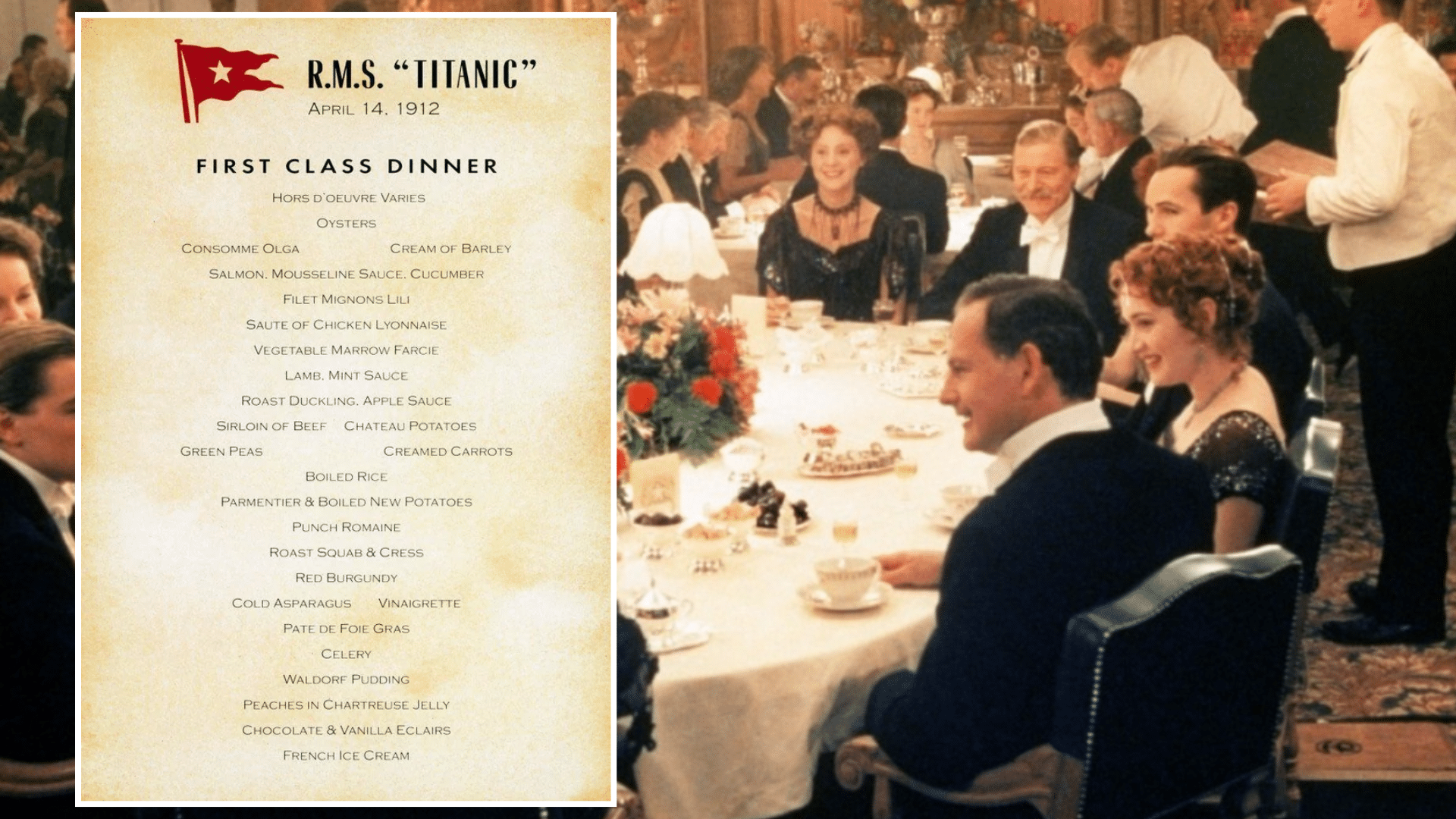

Life aboard the Titanic was divided by wealth. First-class passengers dined on eleven elegant courses. Second-class enjoyed respectable comfort and printed menus. Third-class ate simple, hearty meals on tin plates. The food reflected each passenger’s ticket price and social standing. Even the ship’s elevator only served first and second class—third-class passengers climbed stairs. Nowhere was inequality more visible than at mealtime.

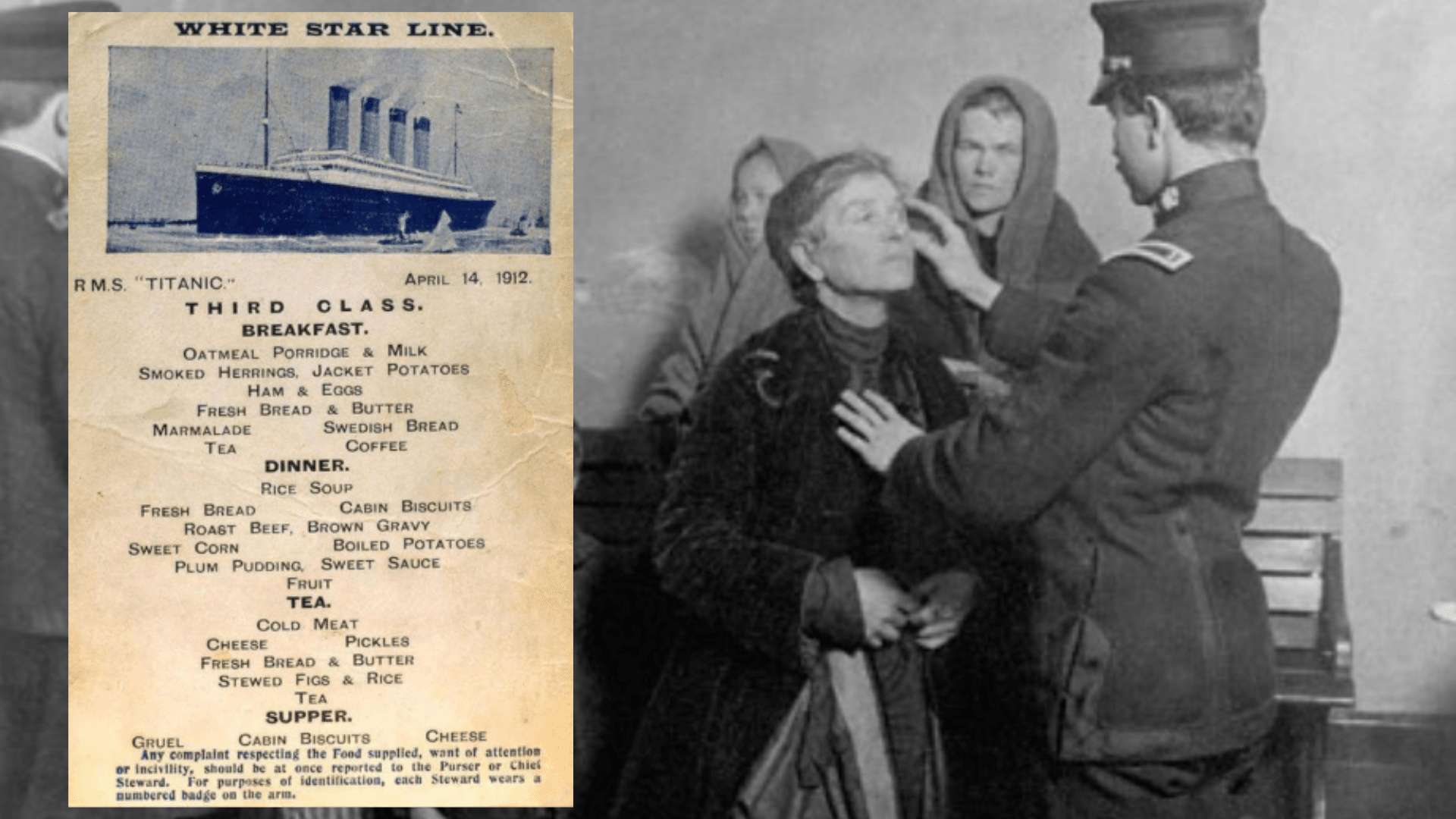

Third Class Breakfast

On the morning of April 14, third-class passengers ate oatmeal porridge, tea, and bread with butter. Many were immigrants from Ireland, Scandinavia, and Eastern Europe heading to America. Ham and eggs were sometimes available but not guaranteed. The setting was plain—tinware plates and communal tables. For many passengers, this was still the most substantial meal they’d had in weeks. It was designed to comfort and sustain them on the long journey ahead.

Smoked Herrings and Swedish Bread

Third-class meals included smoked herrings, jacket potatoes, and marmalade with dry biscuits. Fresh Swedish bread was served to Scandinavian passengers as a familiar comfort. The food was hearty and inexpensive, designed to feed hundreds in steerage. Titanic researcher Bill Willard called third-class fare “far above average” for ships of that era. Though simple, the meals were carefully planned. Even in steerage, the kitchen aimed to offer dignity and balance.

Third Class Dinner

Dinner in the third class started with rice soup and bread. The main course was roast beef with brown gravy, boiled potatoes, and sweet corn. It resembled a traditional Sunday roast, familiar to British and Irish travelers. Dessert was plum pudding with sweet sauce—a rare treat for many passengers. Even in the cheapest cabins, the Titanic’s kitchen made an effort. The meal was filling, warm, and gave passengers a sense of home.

Evening Supper

Supper in third class was light and simple. Passengers were served cabin biscuits and cheese, designed to be easy on digestion. The dense, dry biscuits stored well and doubled as utensils when eaten with soup or jam. They were practical, not glamorous. Food historian Andrew Dalby called them “essential” for long sea voyages. As third-class passengers finished their modest evening meal, the second-class dining saloon was preparing something far more elaborate.

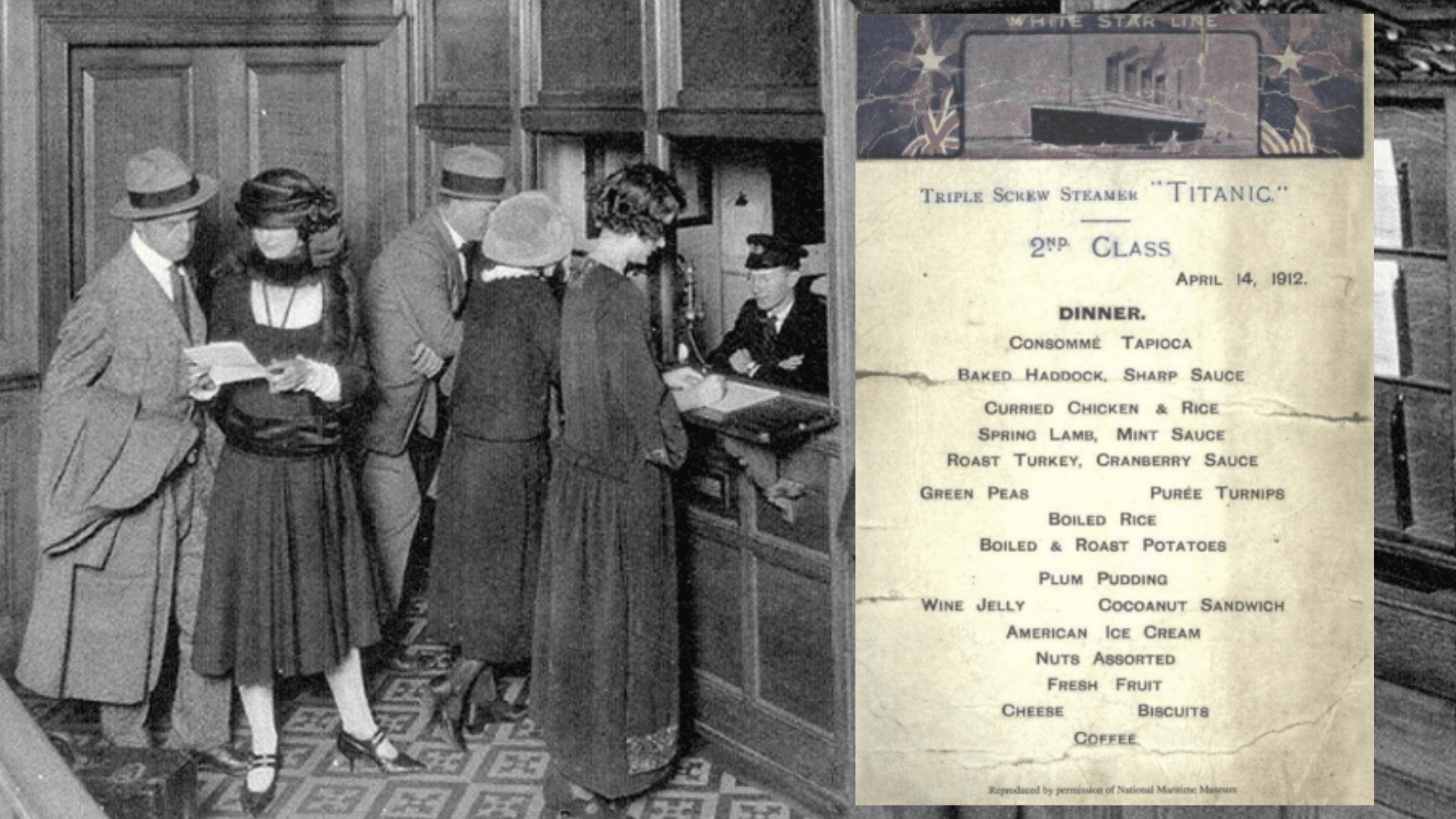

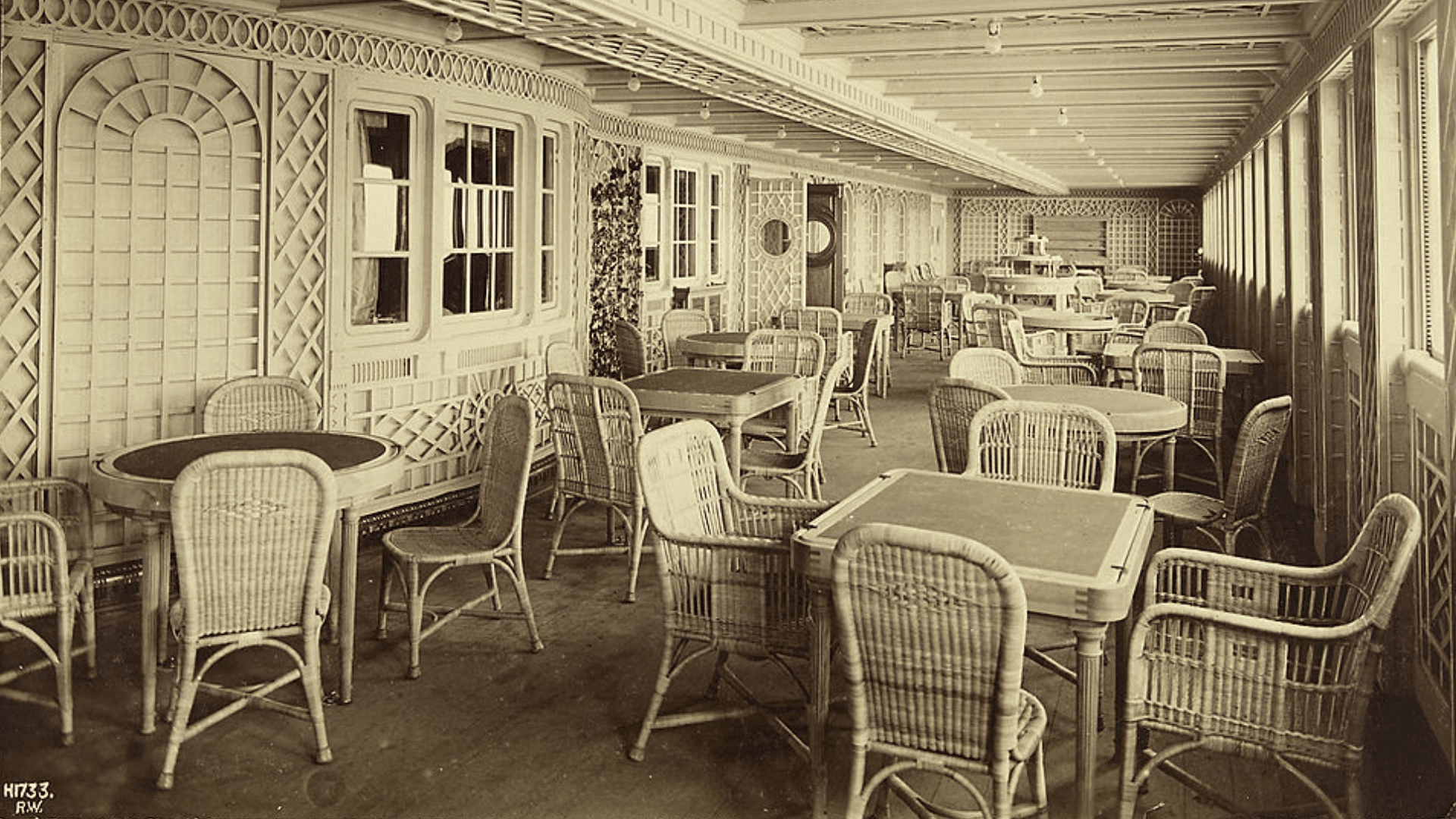

Second Class

Second-class passengers received printed menus and full dinner service. On April 14, they were served roast turkey, spring lamb, boiled potatoes, and American-style ice cream. Meals were served on porcelain, not tin. Waiters wore waistcoats and paced the courses carefully. The dining saloon seated nearly 200 guests in a room designed to look like a provincial English hotel. Titanic researcher Paul Louden-Brown said second class was “equivalent to first class on many other ships.”

Consommé Tapioca and Spring Lamb

Dinner began with consommé tapioca—a clear beef broth with tapioca pearls. It was light and refined, signaling an elevated dining experience. Next came spring lamb with mint sauce, roasted and served with seasonal vegetables. The lamb was tender, the mint familiar and sweet. Cooks adjusted menus throughout the voyage based on freshness and supply. Even in second class, passengers were receiving meals that exceeded expectations for ocean travel.

Roast Turkey and Festive Flavors

Roast turkey with cranberry sauce appeared on the second-class menu, paired with boiled and roasted potatoes. Turkey was a luxury at sea, less common than beef or pork. Its presence suggested a celebratory spirit or Sunday tradition. Records show the Titanic carried over 1,100 pounds of poultry, divided between the classes. The meal echoed festive dinners familiar to British, Irish, and American passengers. It was comfort food elevated for a special voyage.

Plum Pudding and Coconut Sandwiches

Second-class dessert included plum pudding—a steamed dish with dried fruit and spices, served warm with sweet sauce. Also listed was a coconut sandwich, likely a layered confection of coconut and sponge cake. American-style vanilla ice cream was served with biscuits or jelly. Frozen desserts at sea were a novelty at the time. Their inclusion showed the White Star Line’s desire to impress all passengers, not just the wealthy.

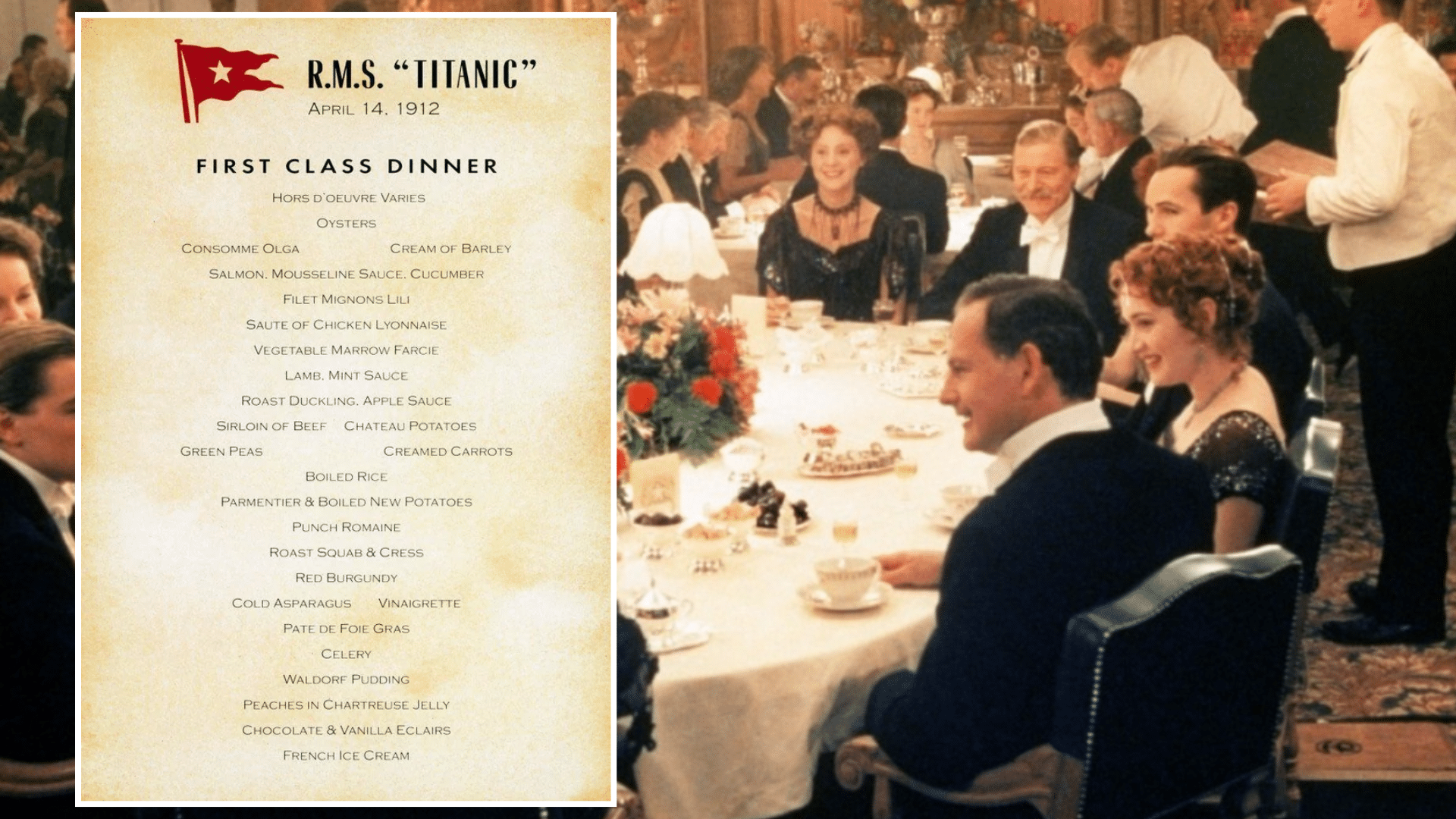

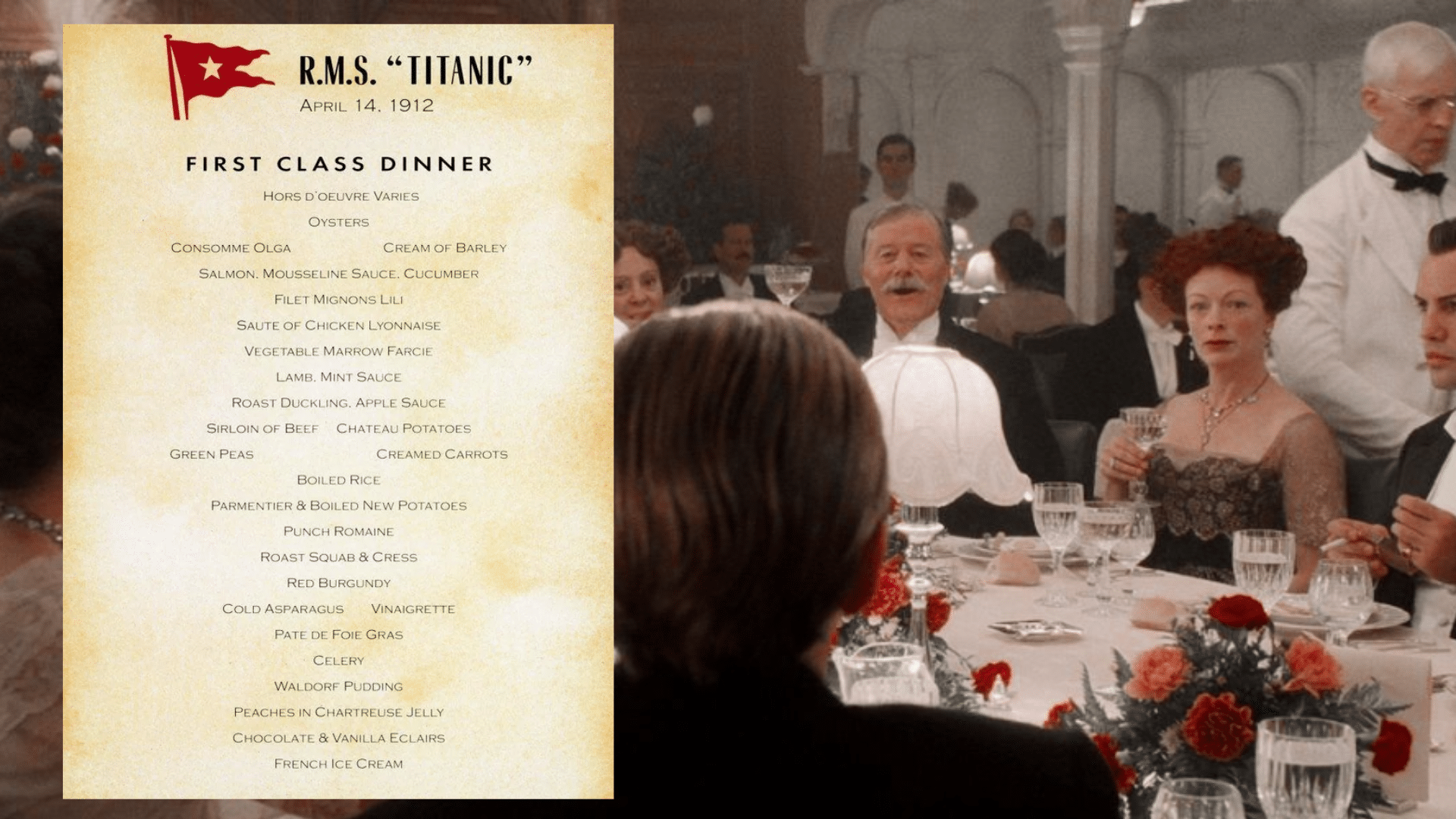

First Class

First-class meals were elaborate, multi-course affairs served beneath crystal chandeliers. The menu for April 14 listed eleven courses, showcasing British ingredients prepared with French techniques. Guests dined on fine china while an orchestra played nearby. The food wasn’t just nourishment—it was social theater. According to White Star Line documents, the Titanic aimed to compete with the Ritz. Every detail was curated for passengers accustomed to luxury hotels and private estates.

Oysters and Hors d’oeuvres

Dinner opened with hors d’oeuvres variés—anchovies, olives, radishes, and pâté. Next came oysters, freshly shucked and served on crushed ice. Historical accounts identify them as Galway oysters, a popular delicacy among upper-class British diners. The oysters were served raw, designed to awaken the palate without overwhelming it. Auctioned first-class menus confirm this pairing. For wealthy passengers, the meal had only just begun.

Filet Mignon and Sautéed Chicken

The entrée list featured filet mignon Lili—beef tenderloin topped with foie gras and black truffle, finished in Madeira sauce. Another option was sautéed chicken Lyonnaise, served over onions and potatoes. Both dishes reflected French haute cuisine at sea. Many of these entrées were preserved in a menu recovered by survivor Abraham Lincoln Salomon. The menu, now time-stained, is one of the last artifacts from the Titanic’s final hours.

Punch Romaine

Midway through the meal came punch Romaine—a frozen sorbet of citrus and rum. It was served in glass stemware and included shaved ice, lemon, orange juice, and champagne. The dish was meant to cleanse the palate before the richer final courses resumed. It was both theatrical and refreshing, more common in luxury resorts than at sea. Food writer Veronica Hinke called it the most memorable dish of the evening due to its elegance and timing.

Waldorf Pudding and Chocolate Éclairs

Dessert featured Waldorf pudding—a baked custard with dried fruit and walnuts. Éclairs filled with vanilla or chocolate cream followed, piped fresh, and finished with glaze. Pâté de foie gras was served with toasted brioche. Wine flowed throughout dinner—red Burgundy with beef, white wines with seafood, and champagne with dessert. The meal lasted two to three hours. Guests changed into evening wear, and the entire experience was a social and culinary ritual.

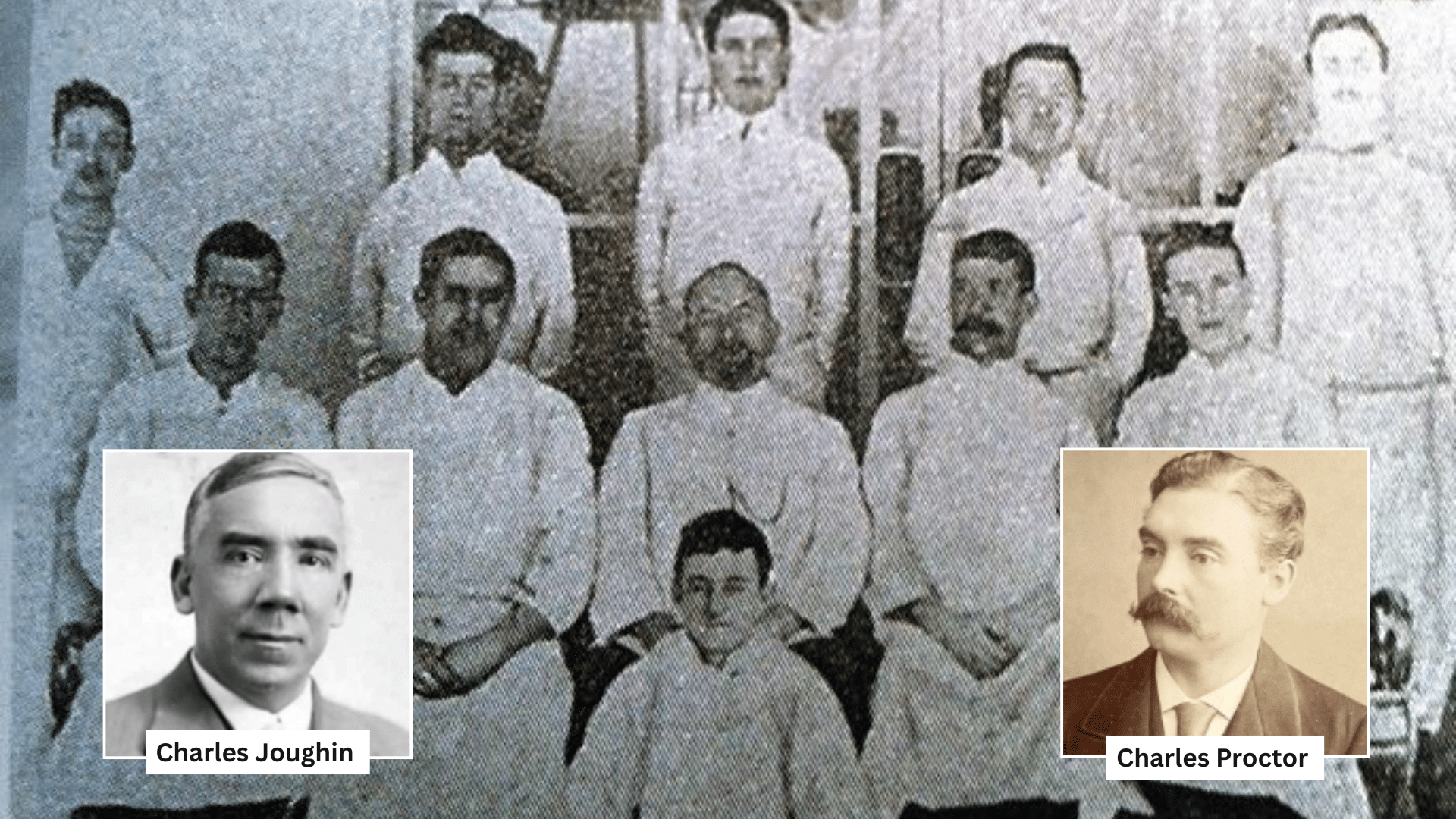

The Kitchens

Over 60 staff handled food prep, service, and cleanup. Titanic carried 75,000 pounds of meat, 11,000 pounds of fresh fish, and 40 tons of potatoes. The bakery produced over 1,000 loaves of bread daily. Charles Joughin was chief baker, while Charles Proctor oversaw the entire culinary team. Galley logs show daily outputs scaled to feed more than 2,200 people. Most kitchen staff perished during the sinking, their labor now remembered through the menus they served.

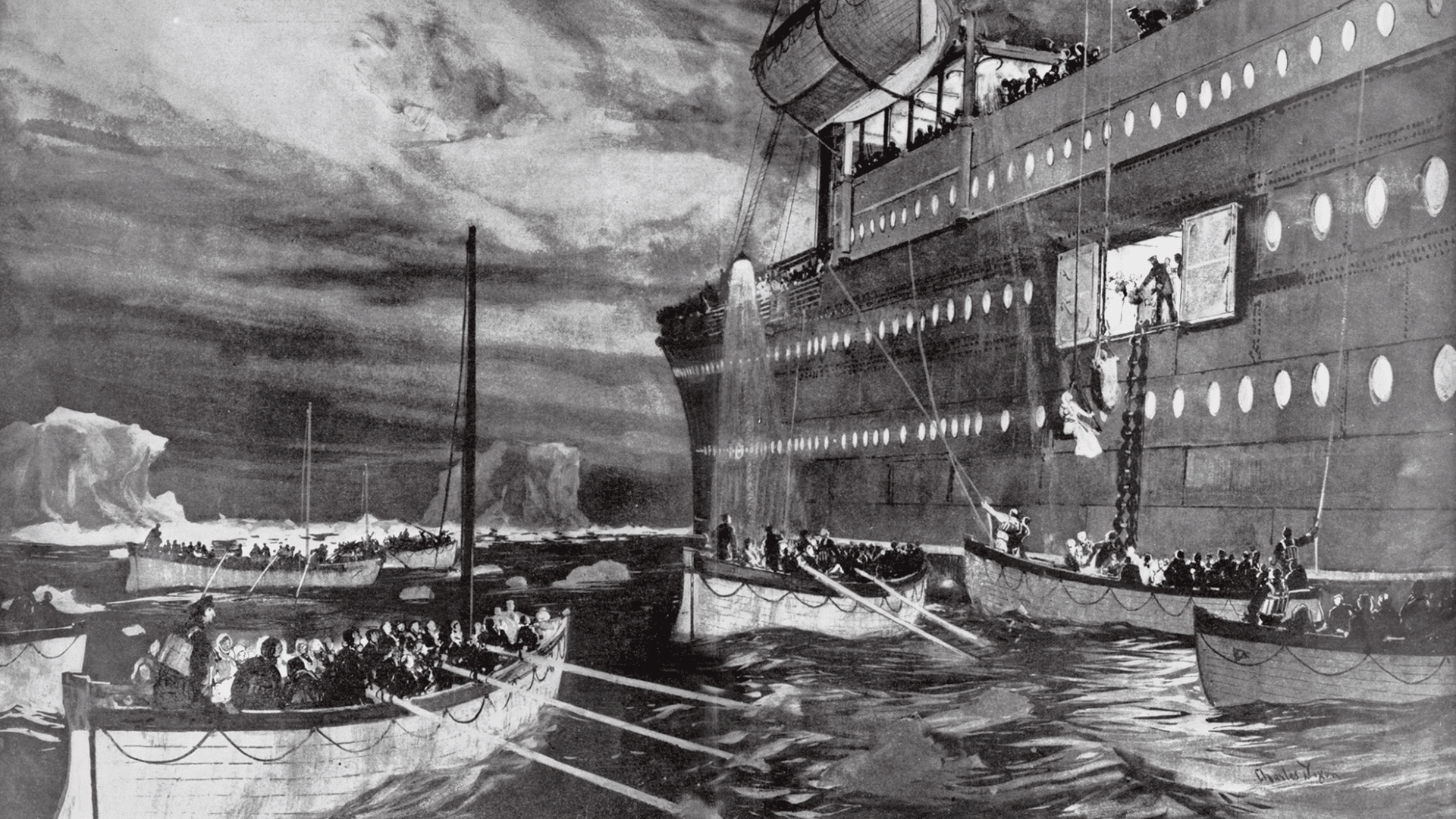

The Iceberg Strikes

At 11:40 PM, a sudden jolt ran through the ship’s hull. A scraping sound followed. Most passengers assumed it was minor. No alarm, no panic. Below deck, the scullery had gone still. Above, a few guests were still sipping brandy, utterly unaware they’d just eaten their last meal. Of the 2,240 people aboard, more than 1,500 would not survive. The dinner never cleared became a meal paused beneath the sea.

Menus Rescued from the Water

Titanic’s menus have become rare artifacts. One first-class menu from April 14, 1912, sold for $102,000 at auction in 2012. Others reside in maritime museums in Belfast, Halifax, and Southampton. These menus weren’t designed to last—they were printed daily and meant to be discarded. Their survival is due to chance and a few passengers’ instinct to save them. Today, they’re displayed under glass as silent witnesses to a vanished world.

Remembering Through Taste

The Titanic is remembered for its engineering, passengers, and tragedy. But its food offers an intimate lens through which to understand the voyage. We can now read what they read, eat what they ate, and imagine conversations over consommé, pudding, or potatoes. This was the menu of the world’s most famous sea voyage—revealed more than a century later, one dish at a time, carrying the memory of those who never returned.